1.01 Introduction to HTML5

1.02 The Evolution of HTML

1.03 How it Works: The “Magic” of Page Requests

1.04 Looking at Your Browser Options

1.05 Editors: How to Use an Editor to Create an HTML File

1.06 Editors: How to Use VS Code

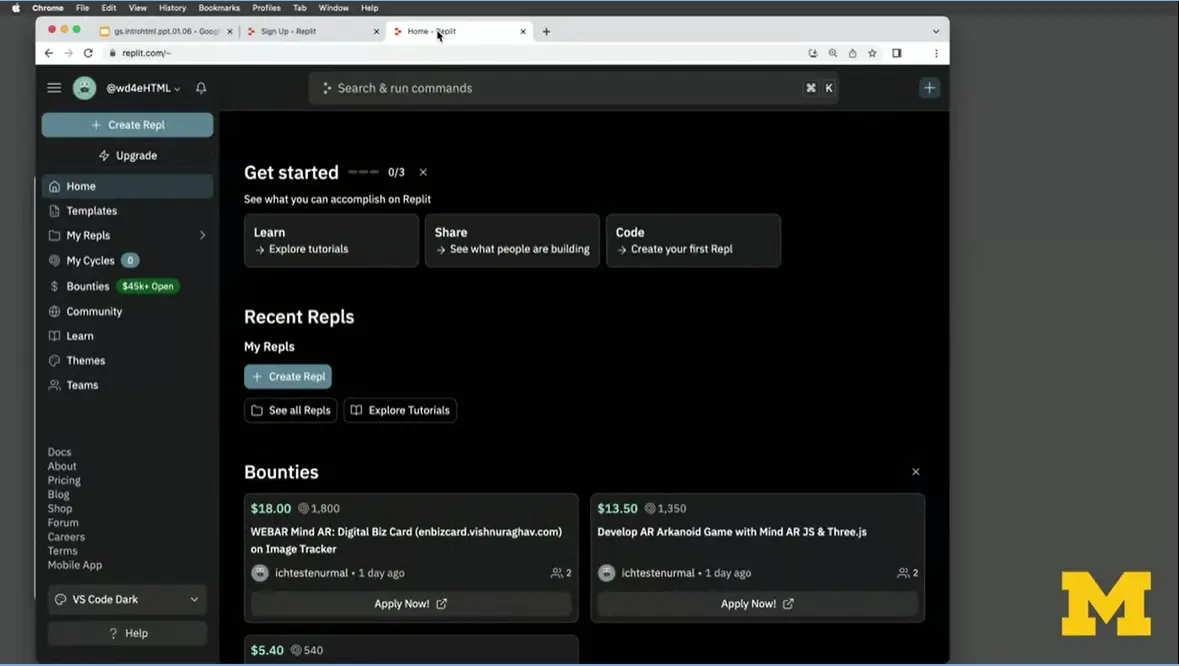

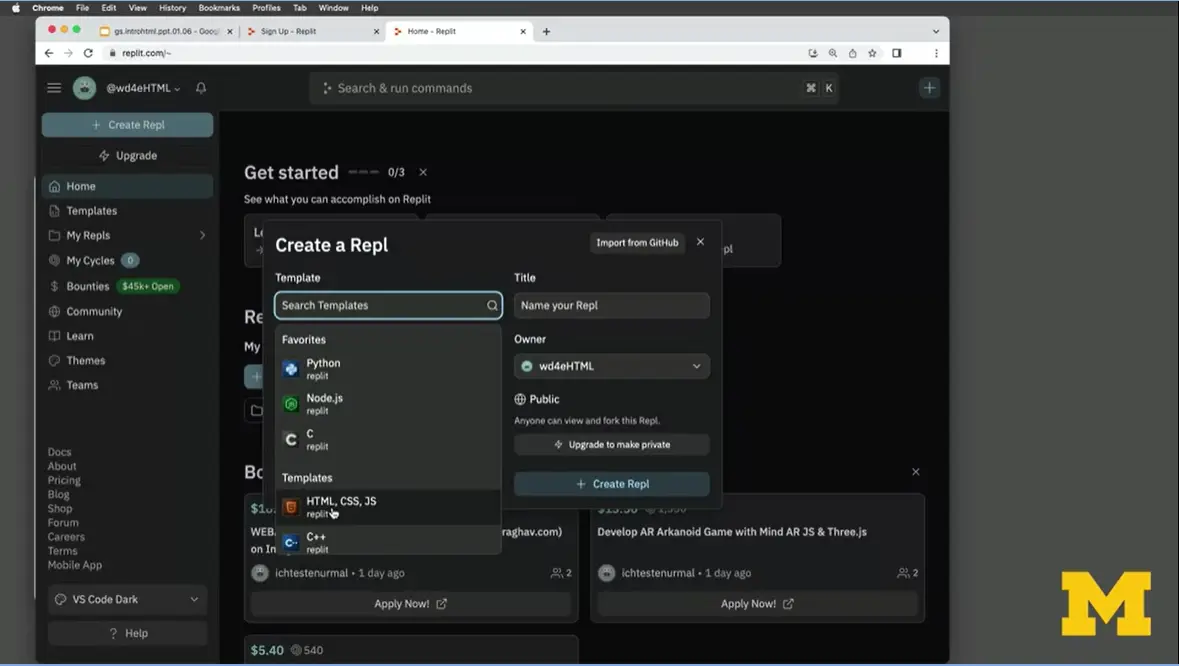

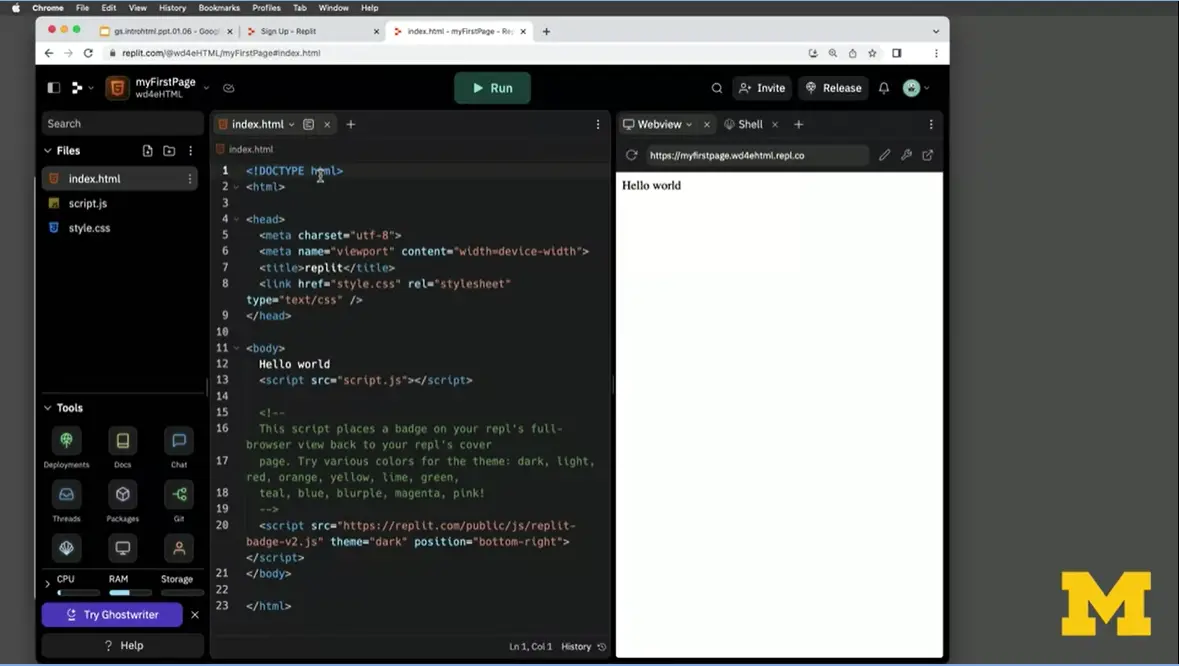

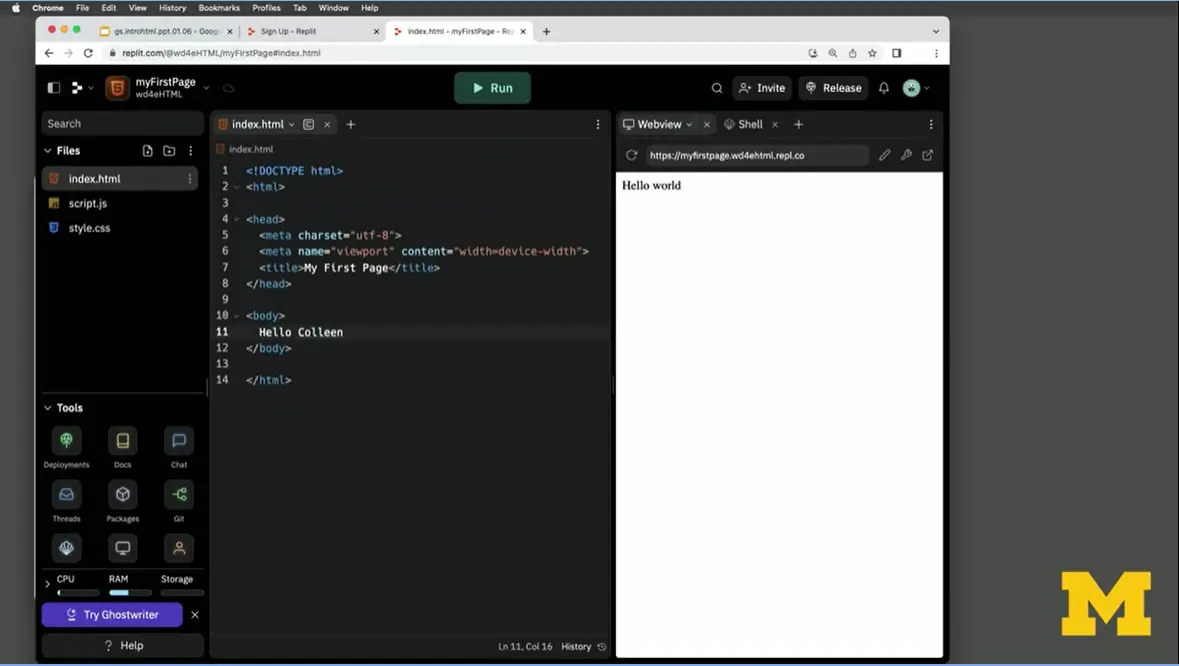

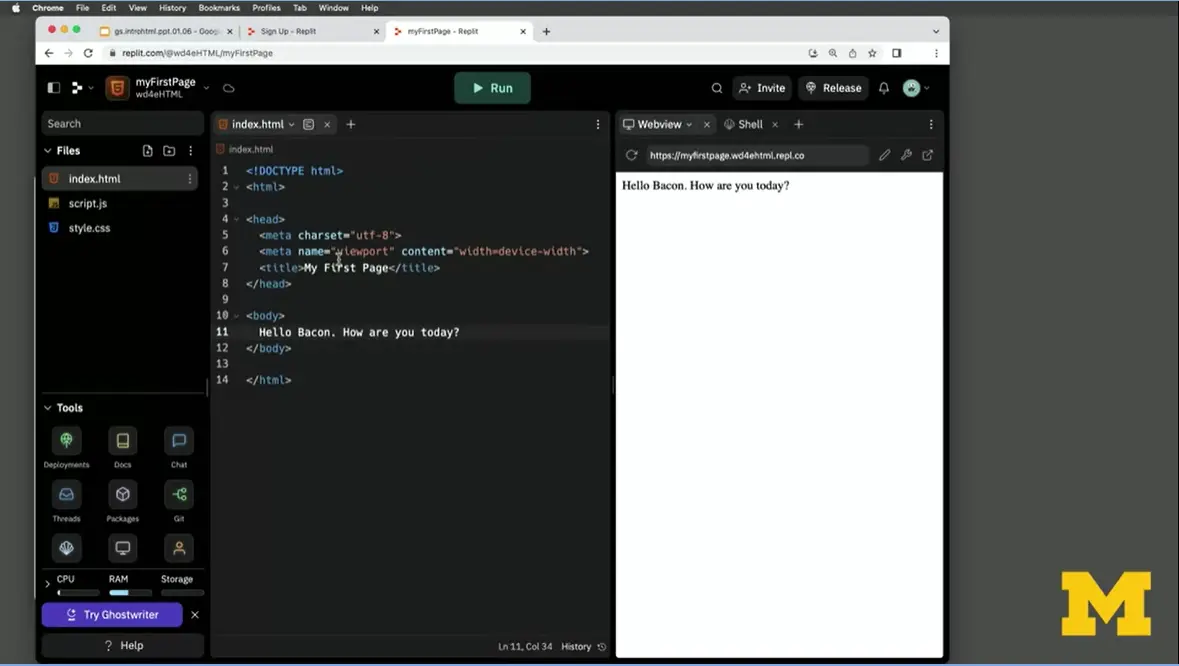

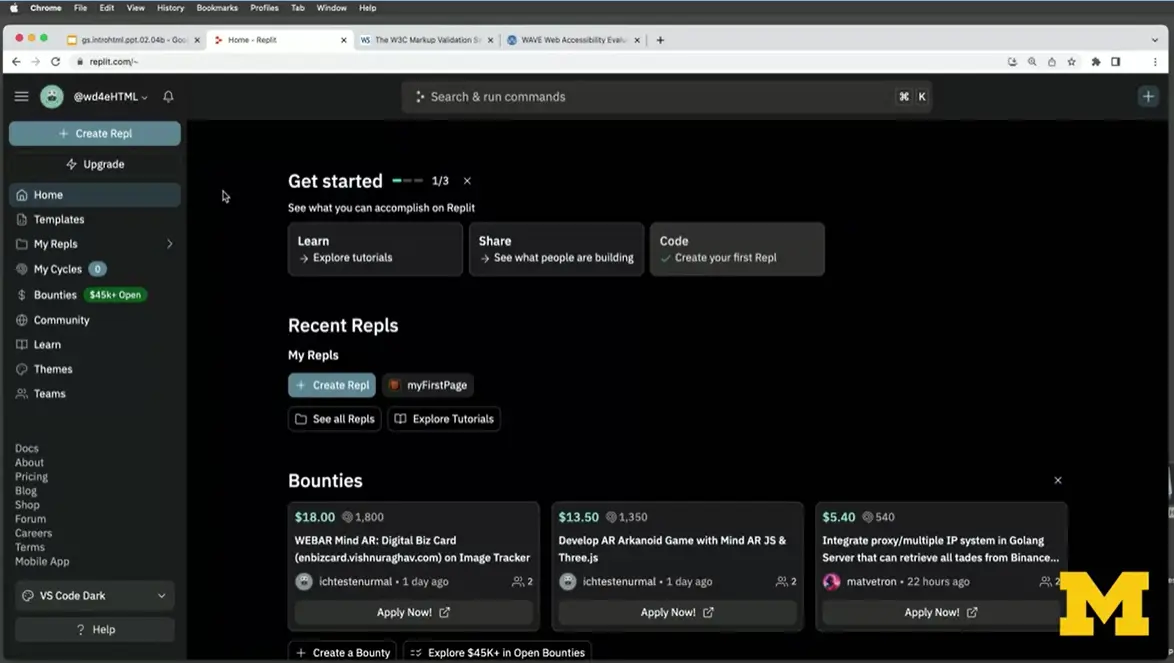

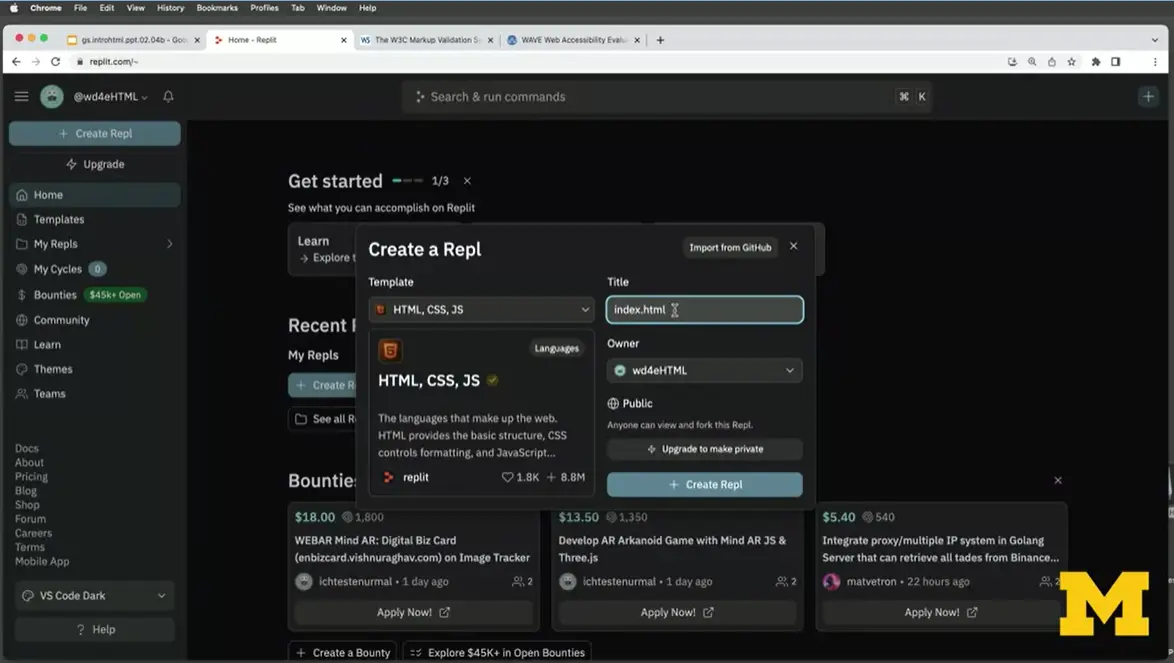

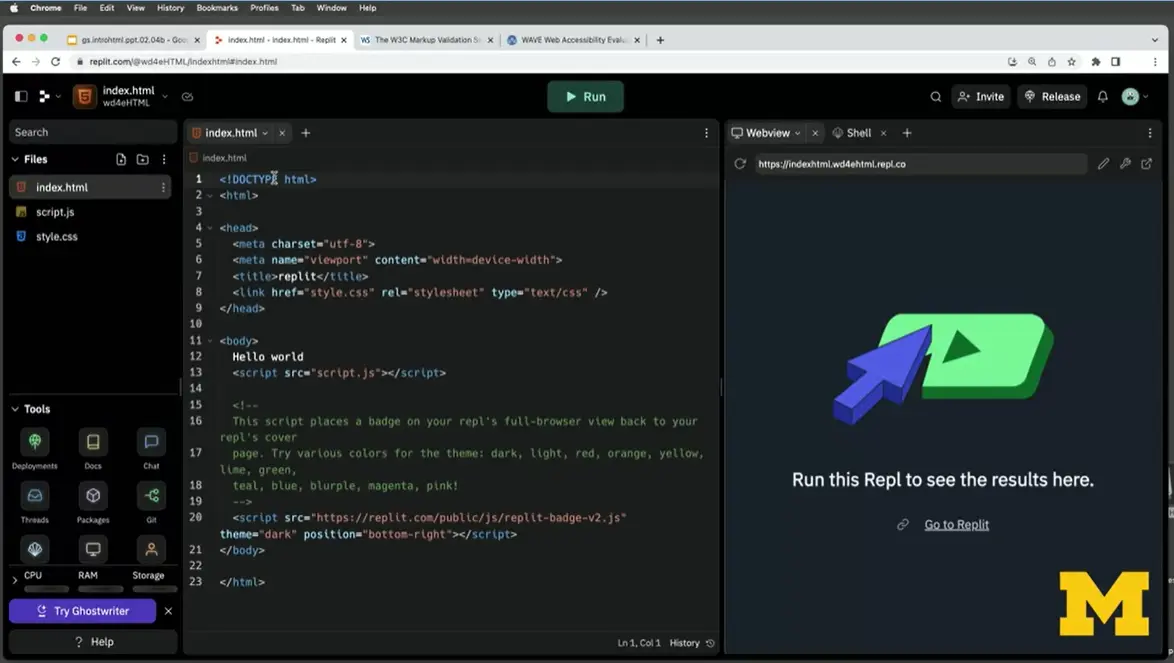

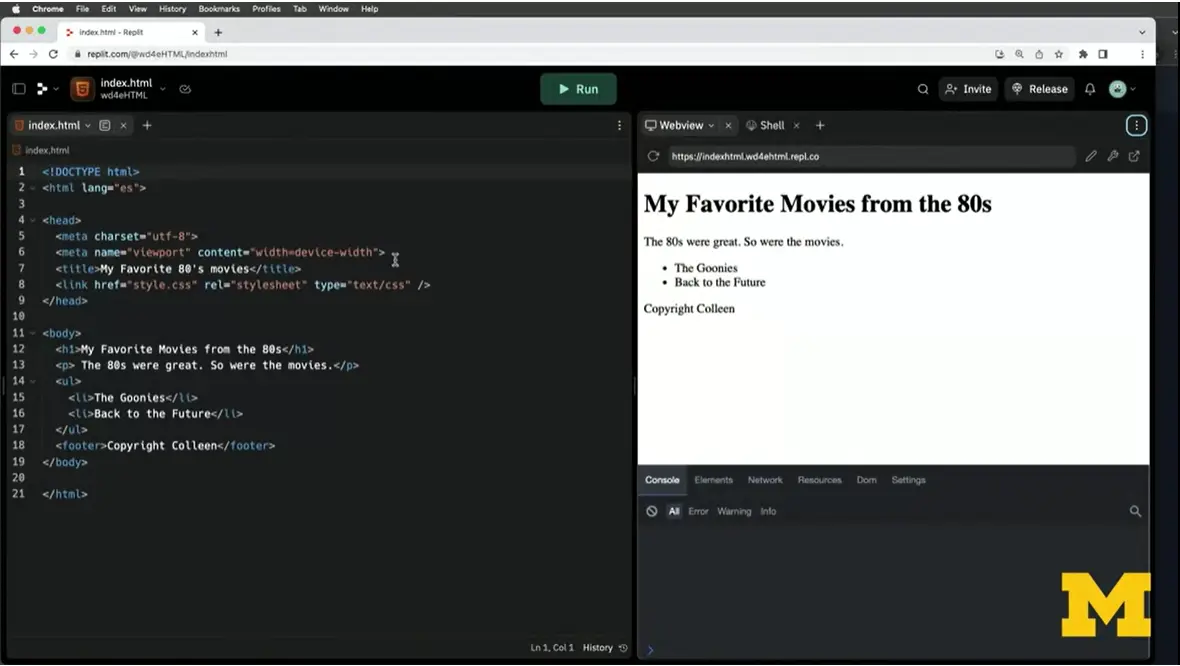

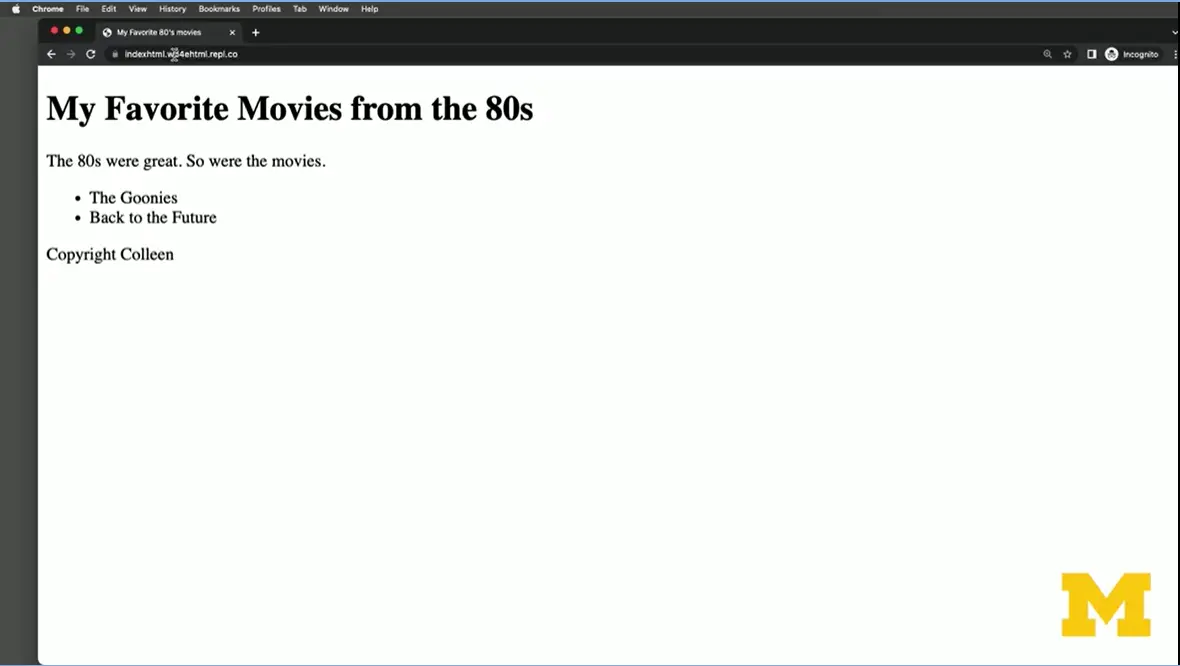

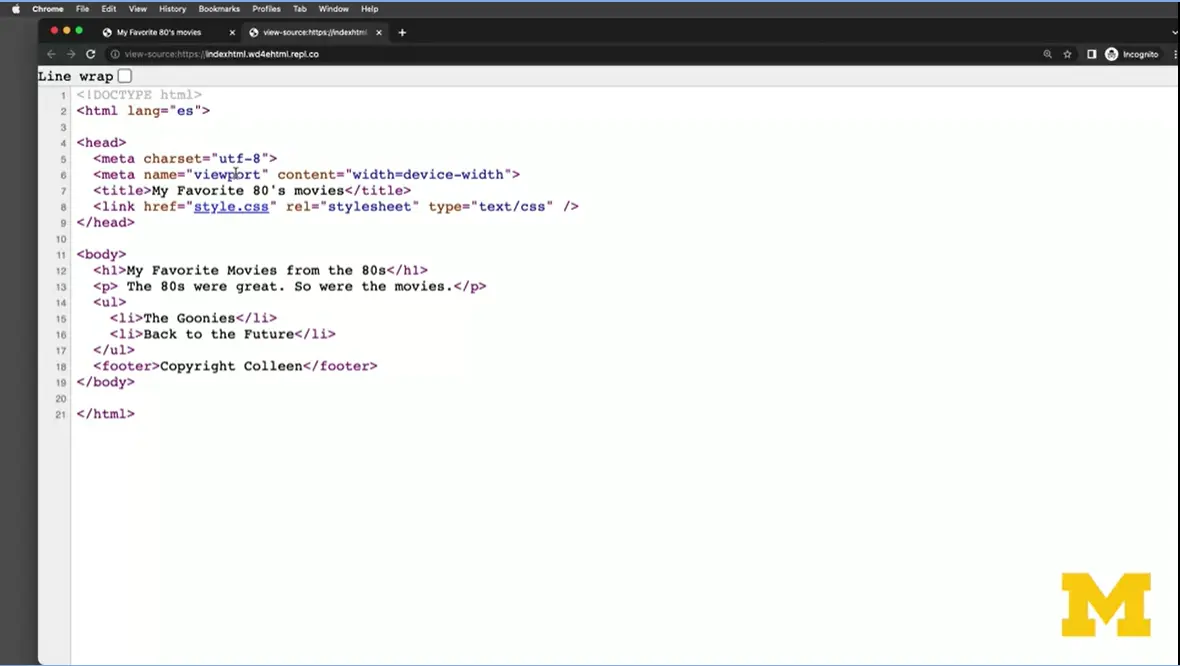

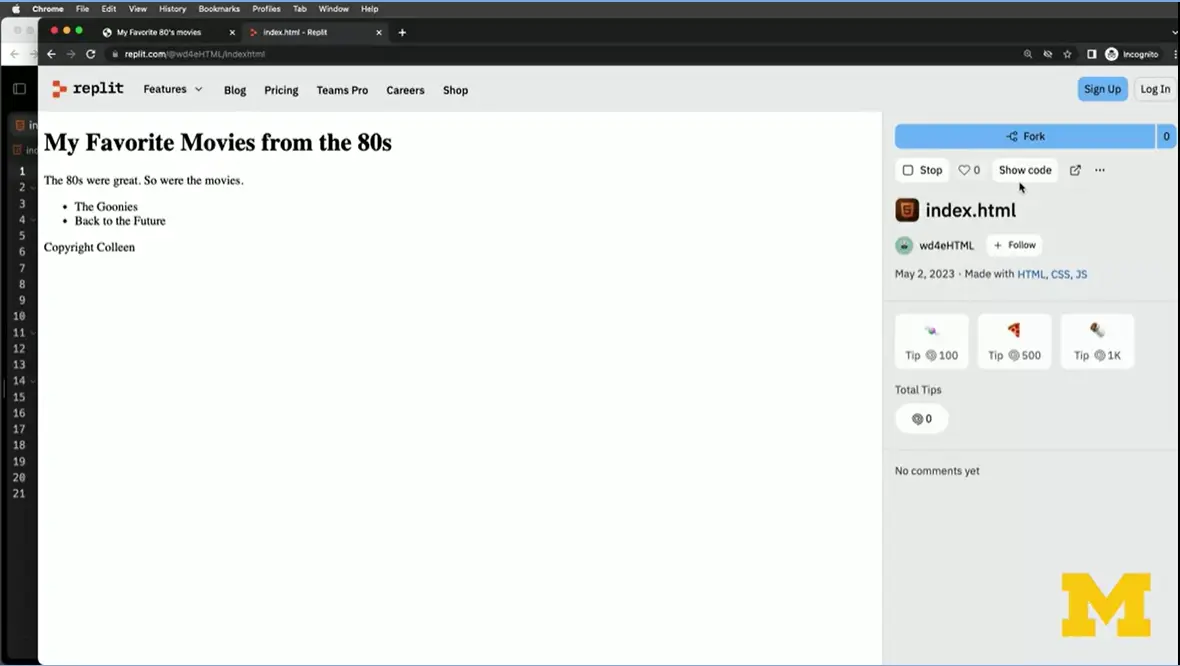

1.07 Editors: How to Use Replit

2.01 The Document Object Model (DOM)

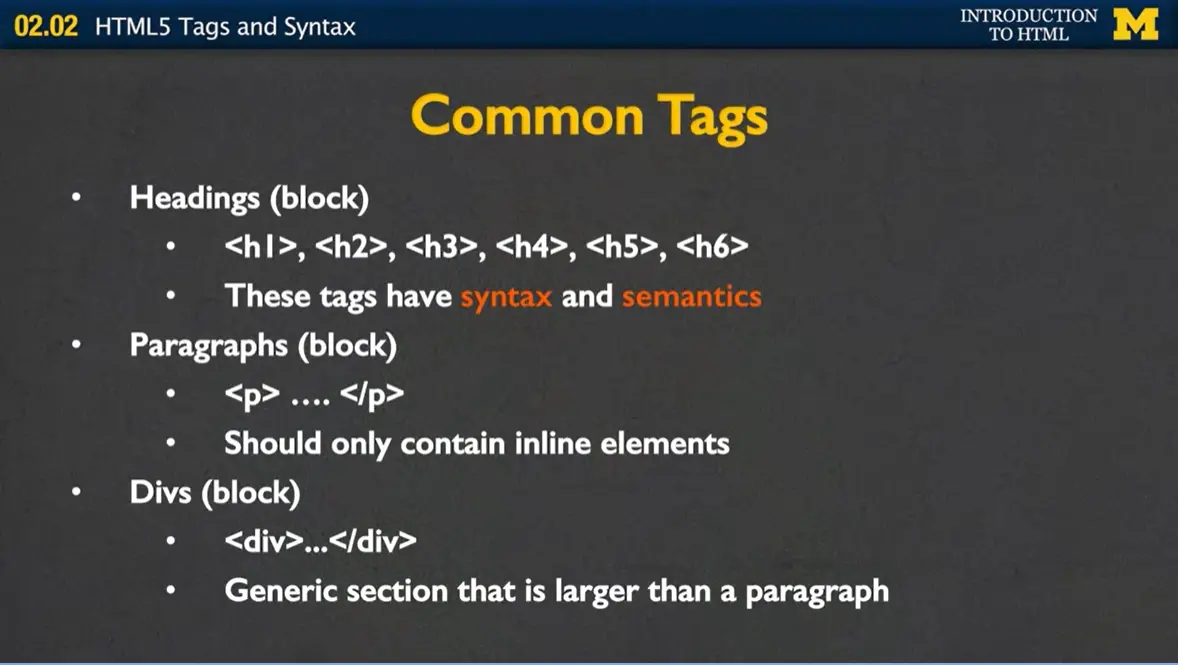

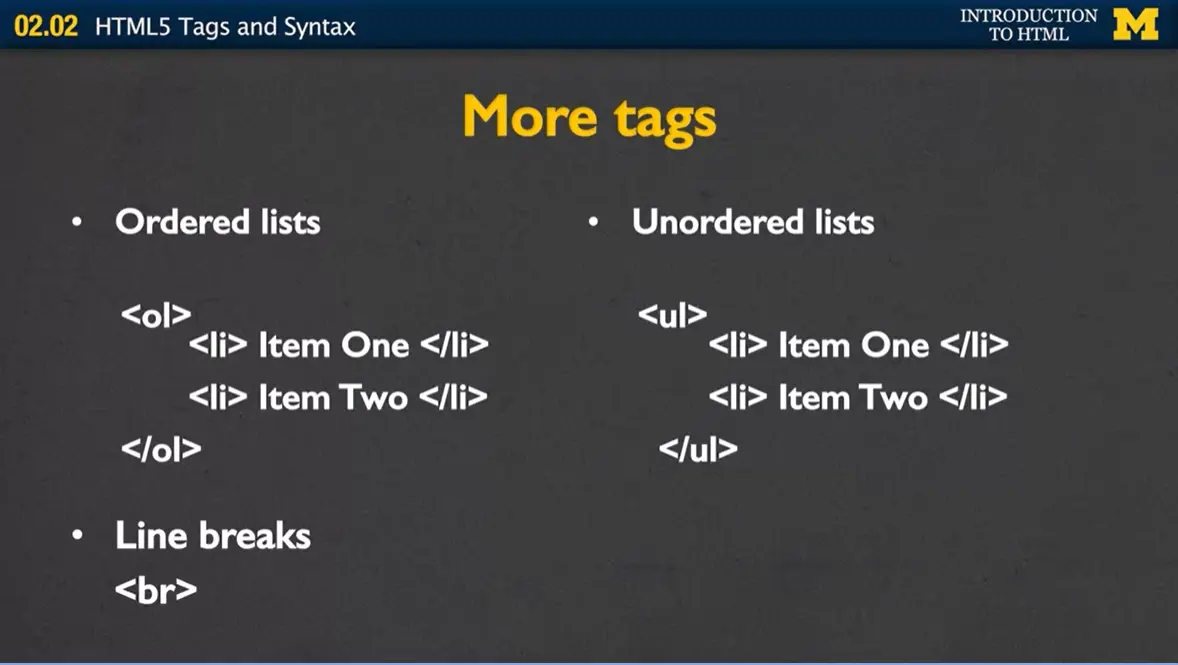

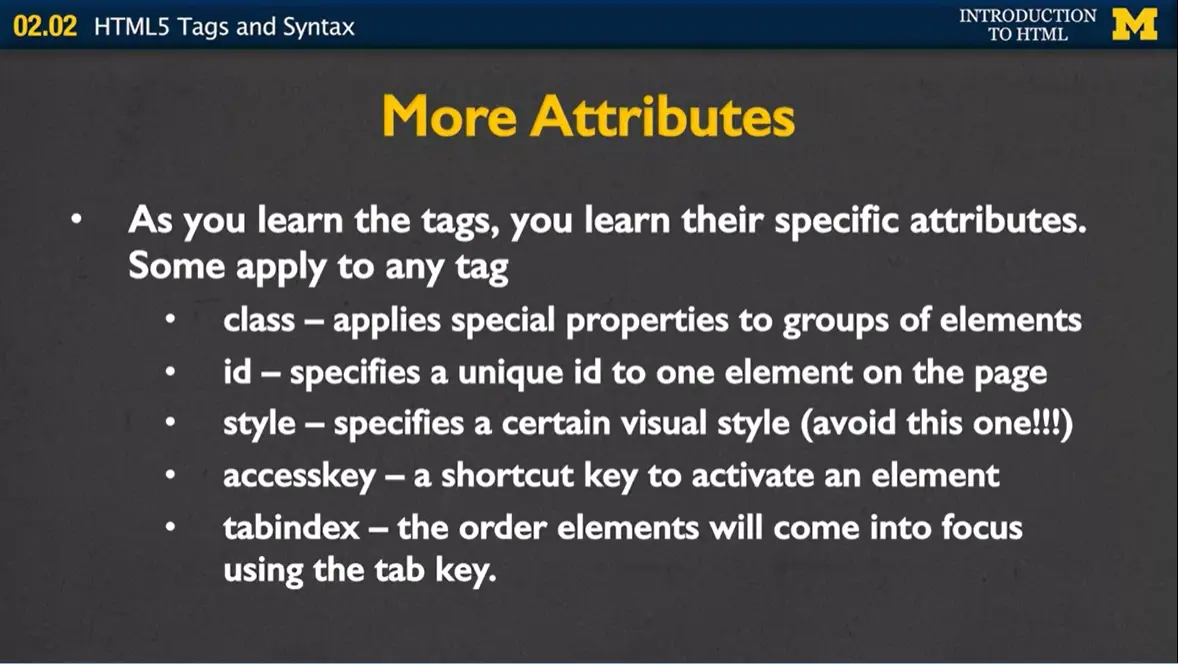

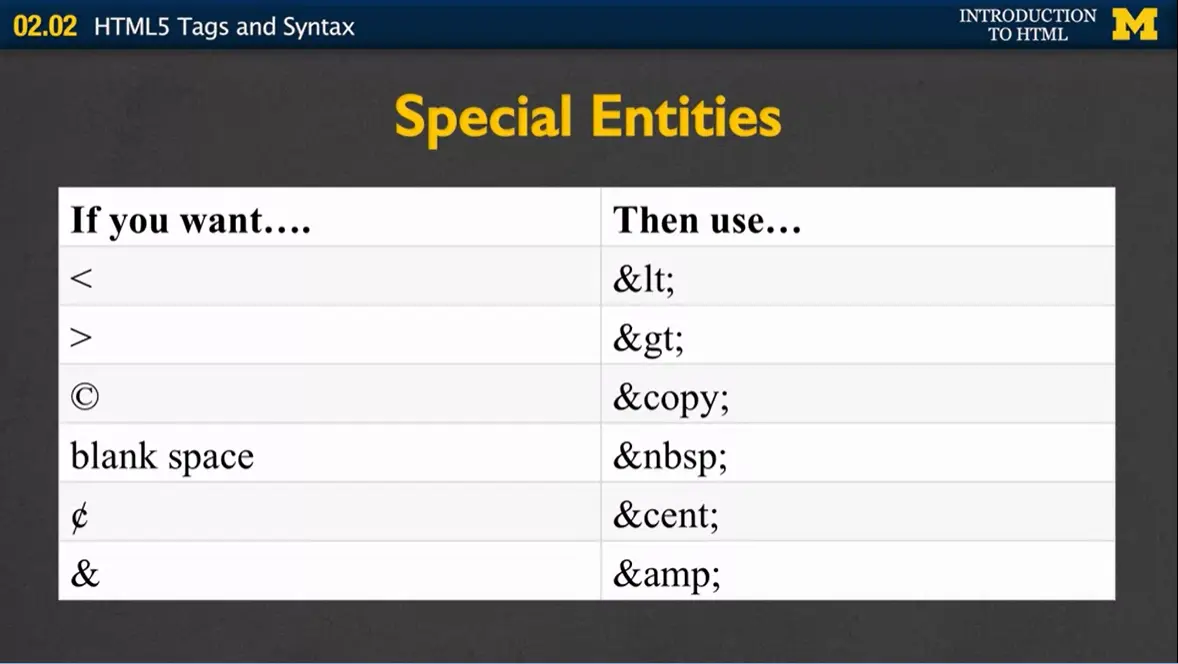

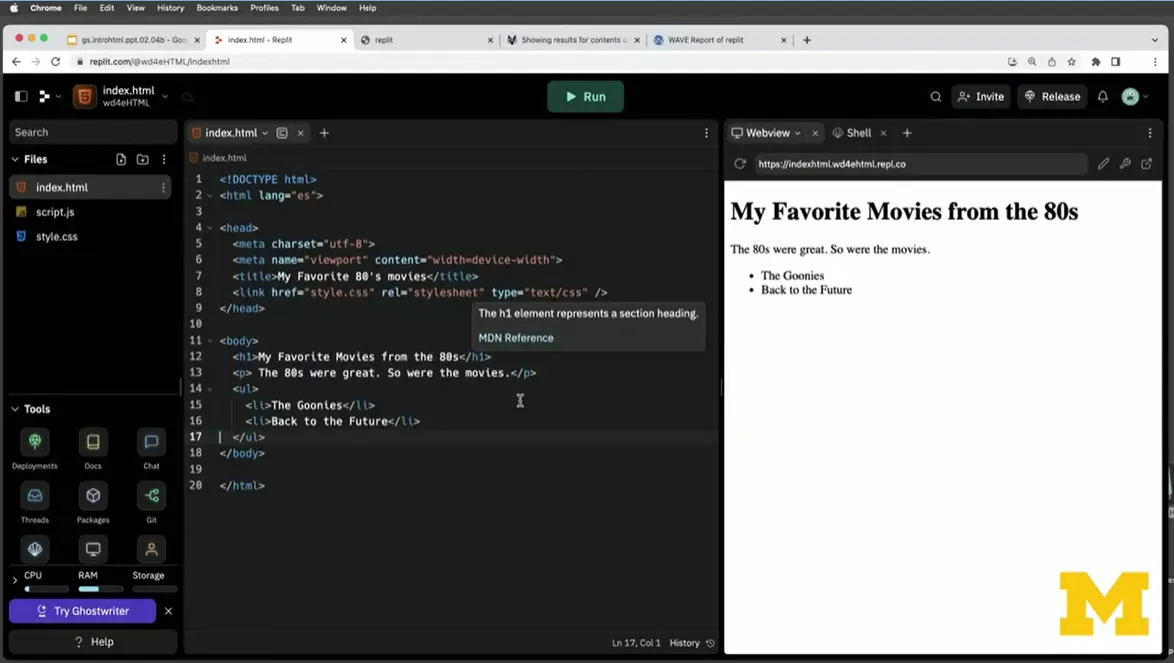

2.02 HTML5 Tags and Syntax

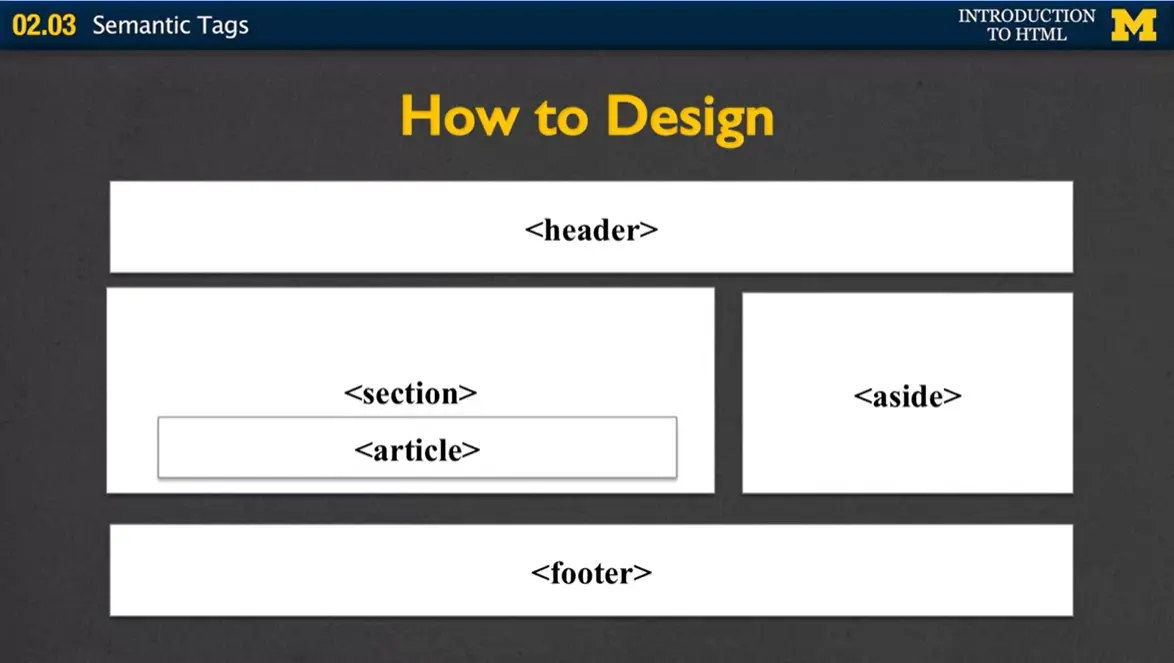

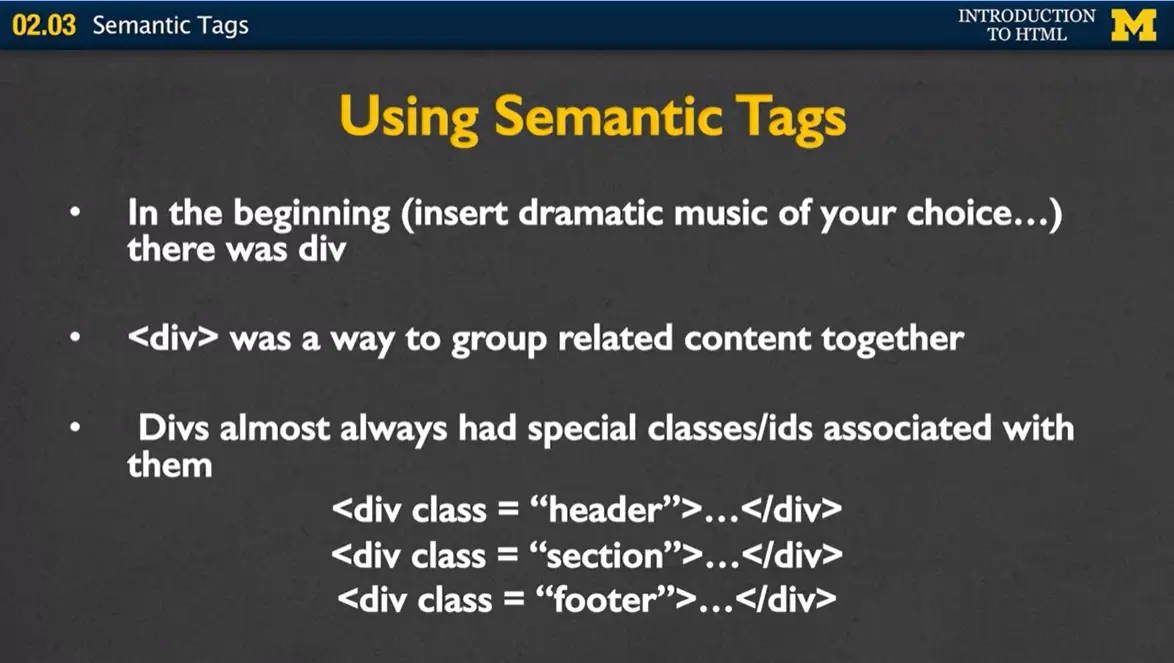

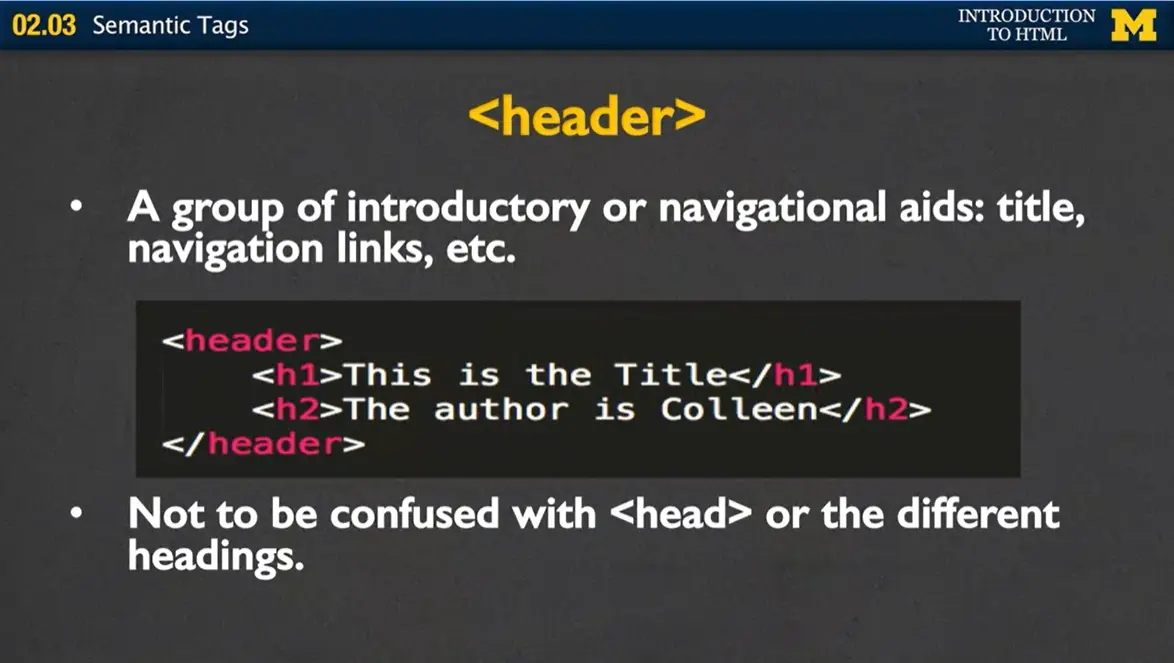

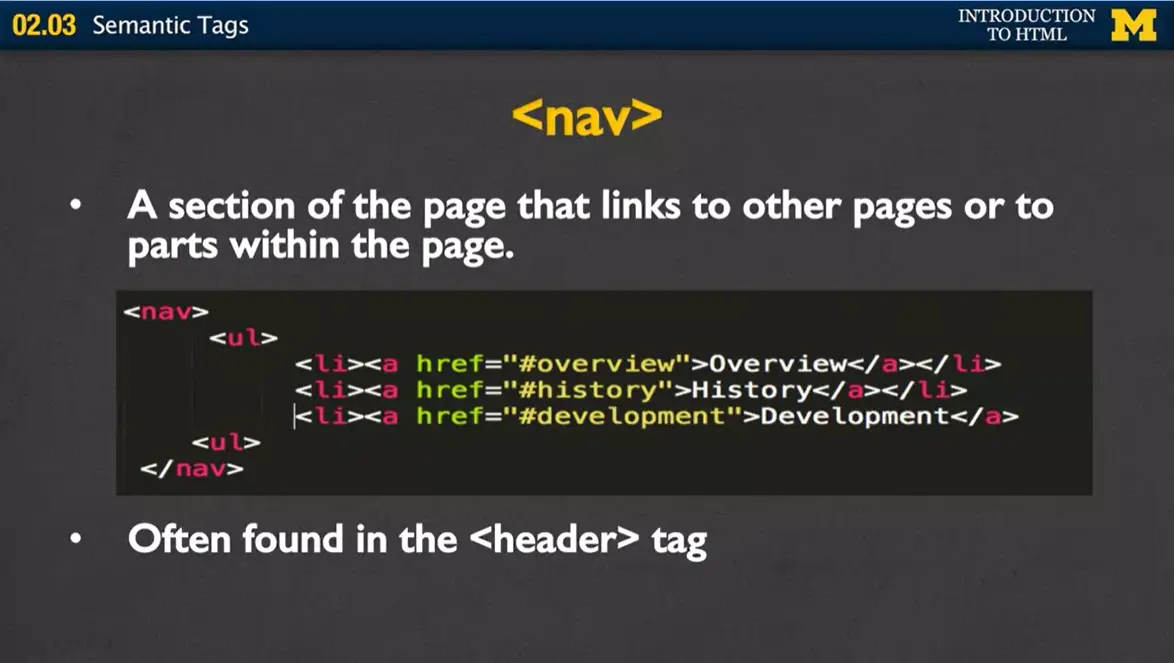

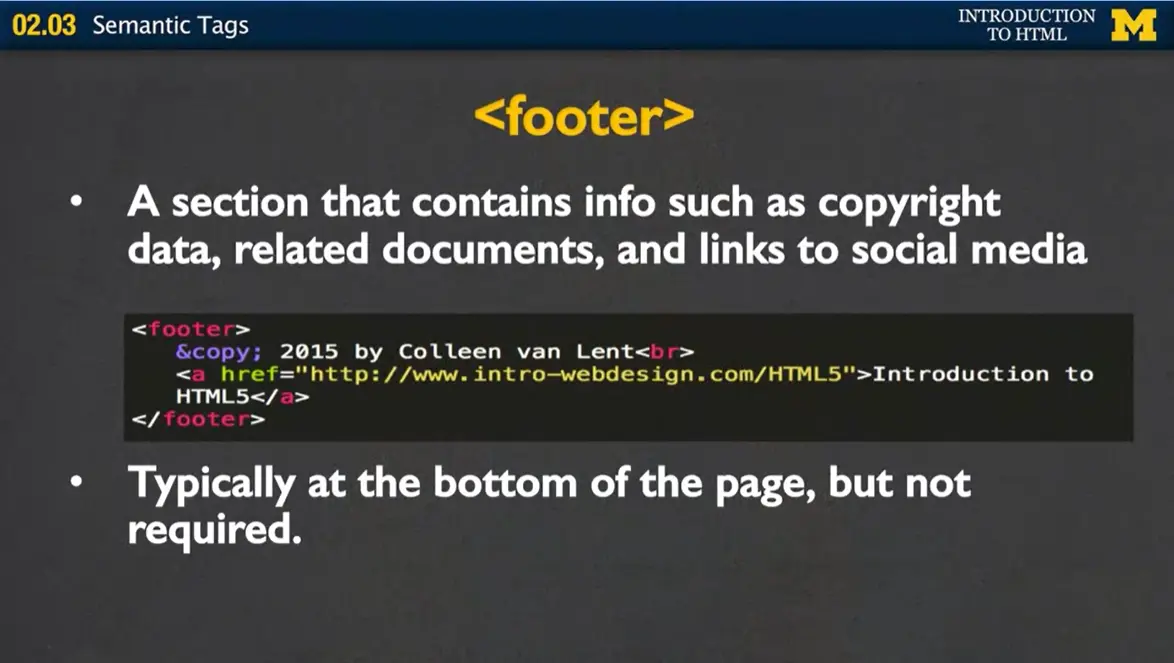

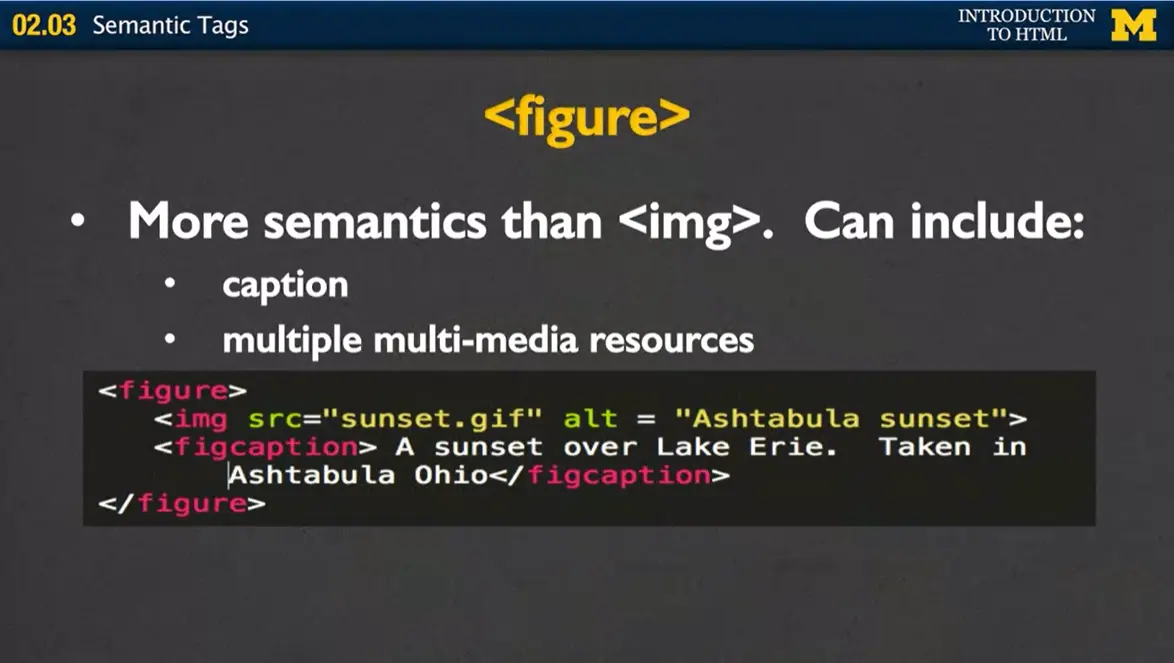

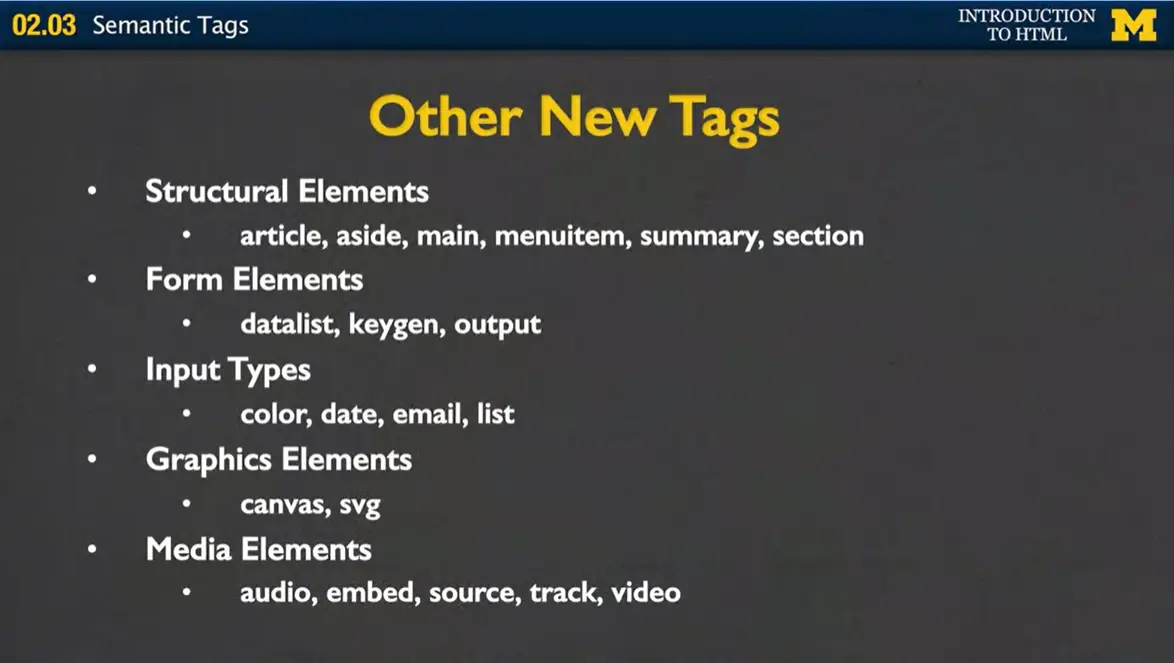

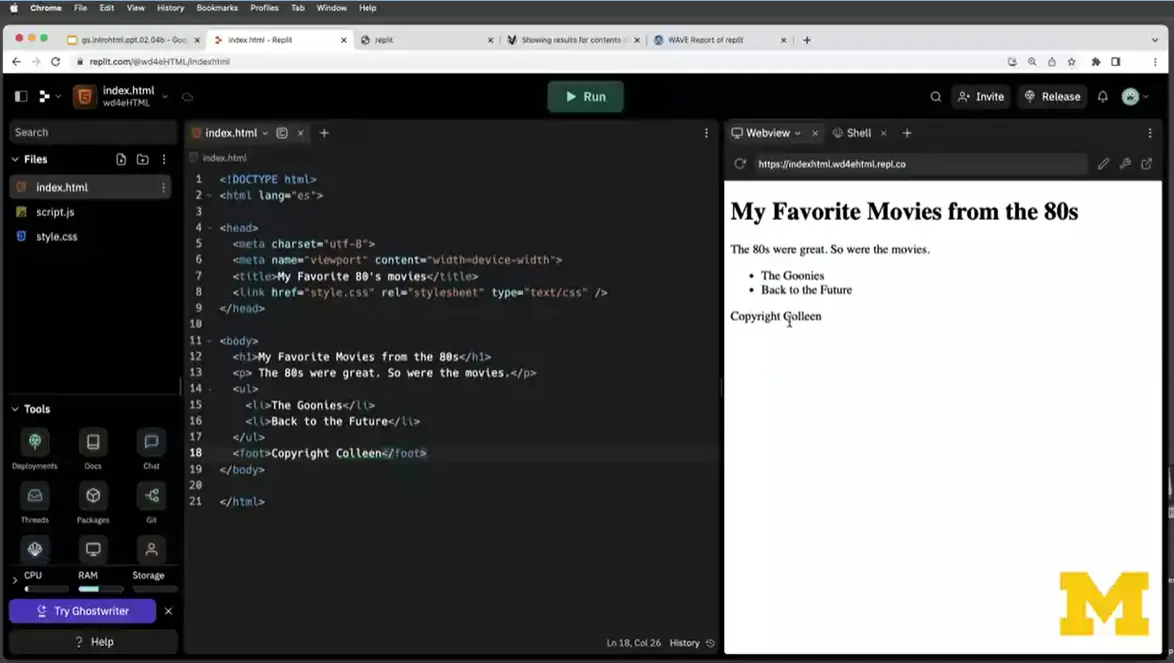

2.03 Semantic Tags

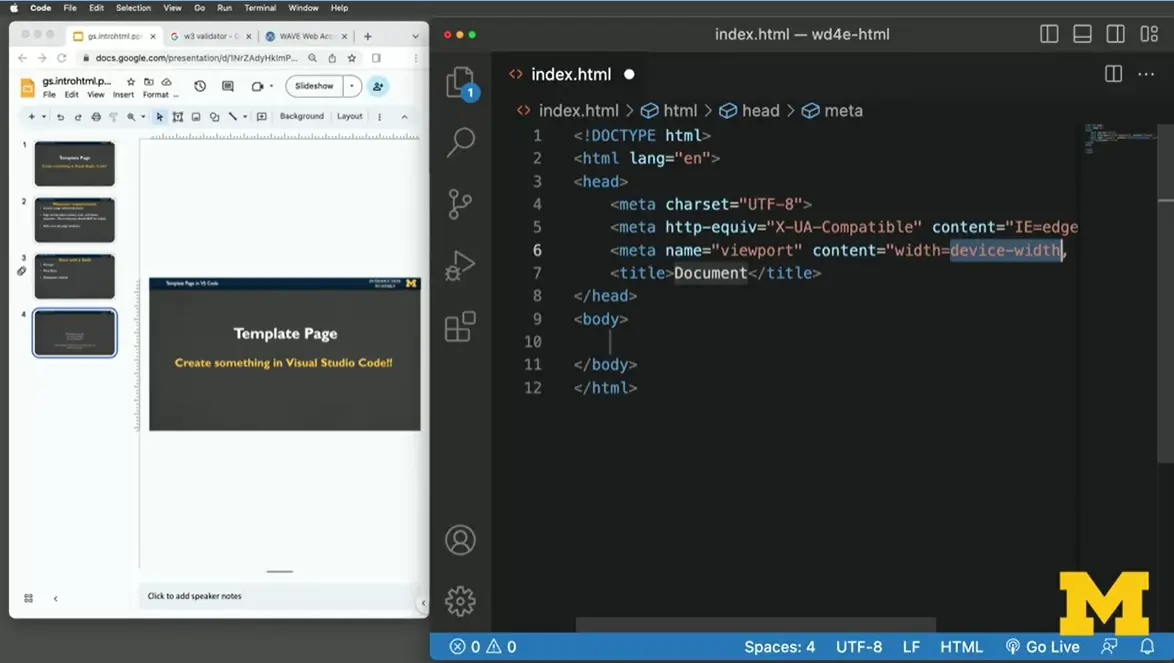

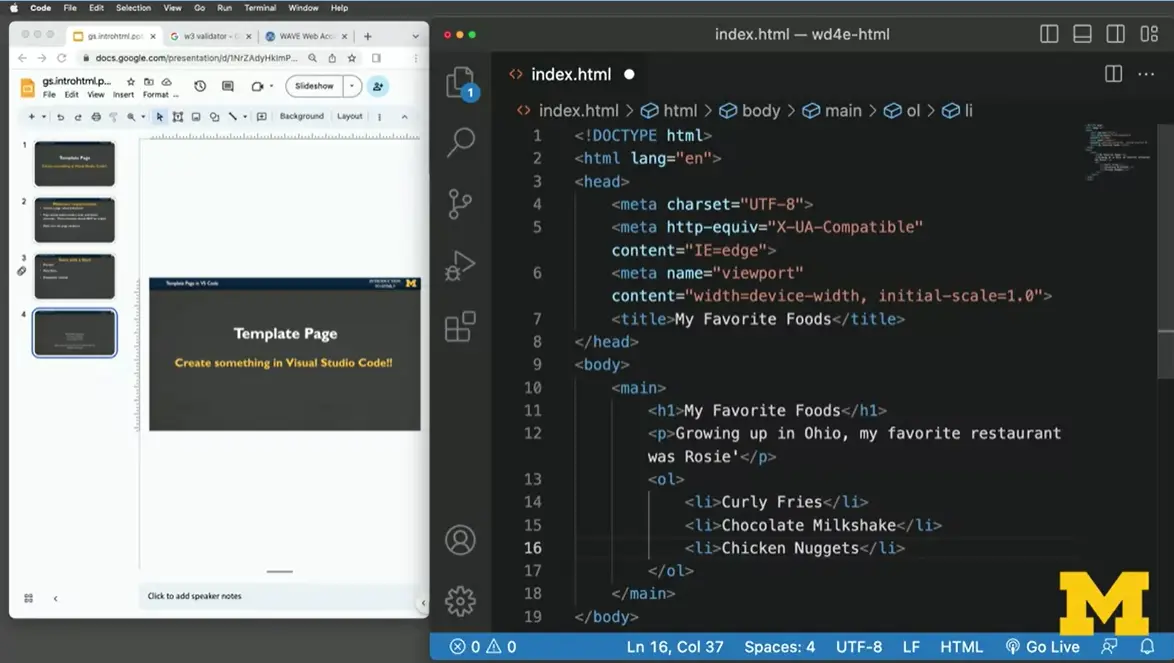

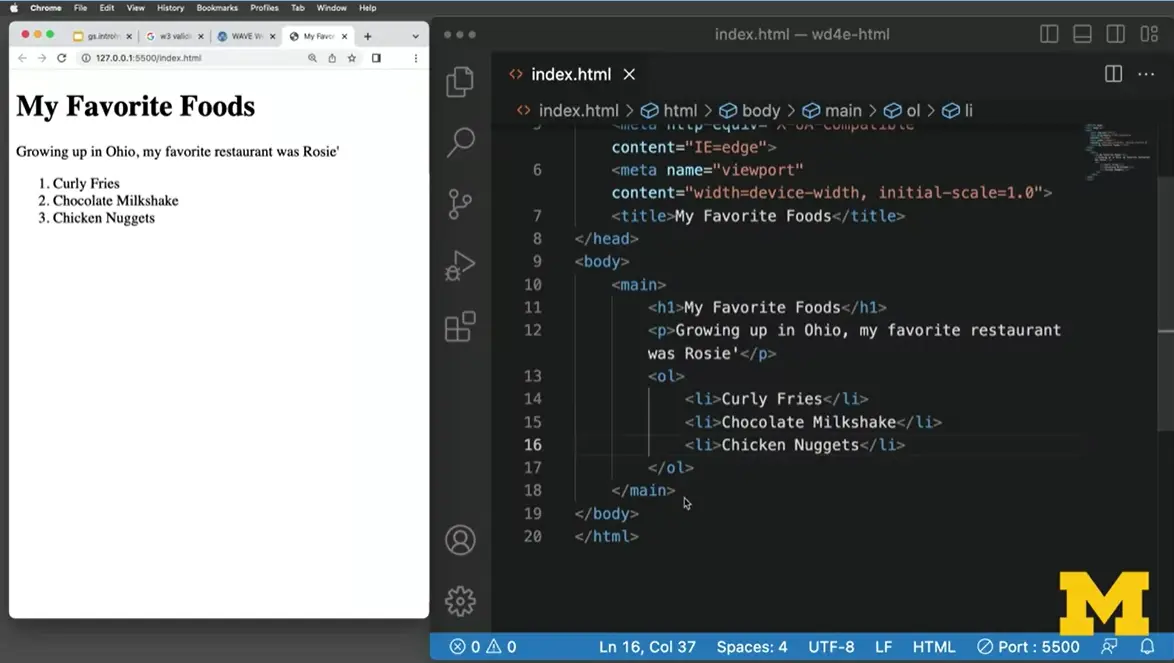

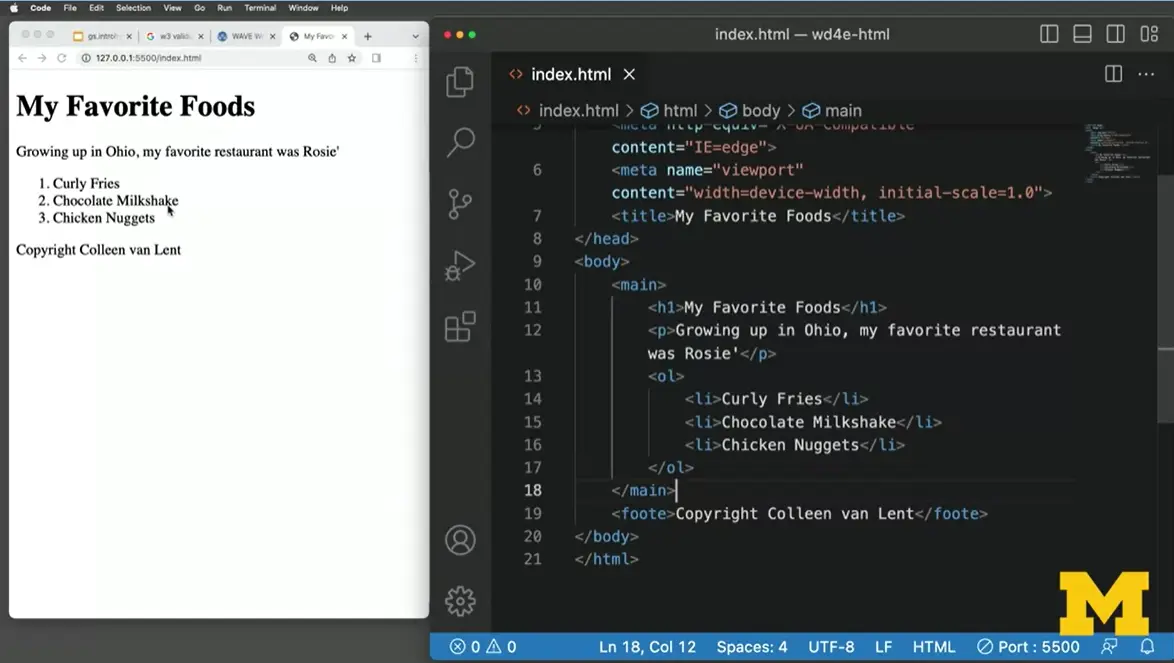

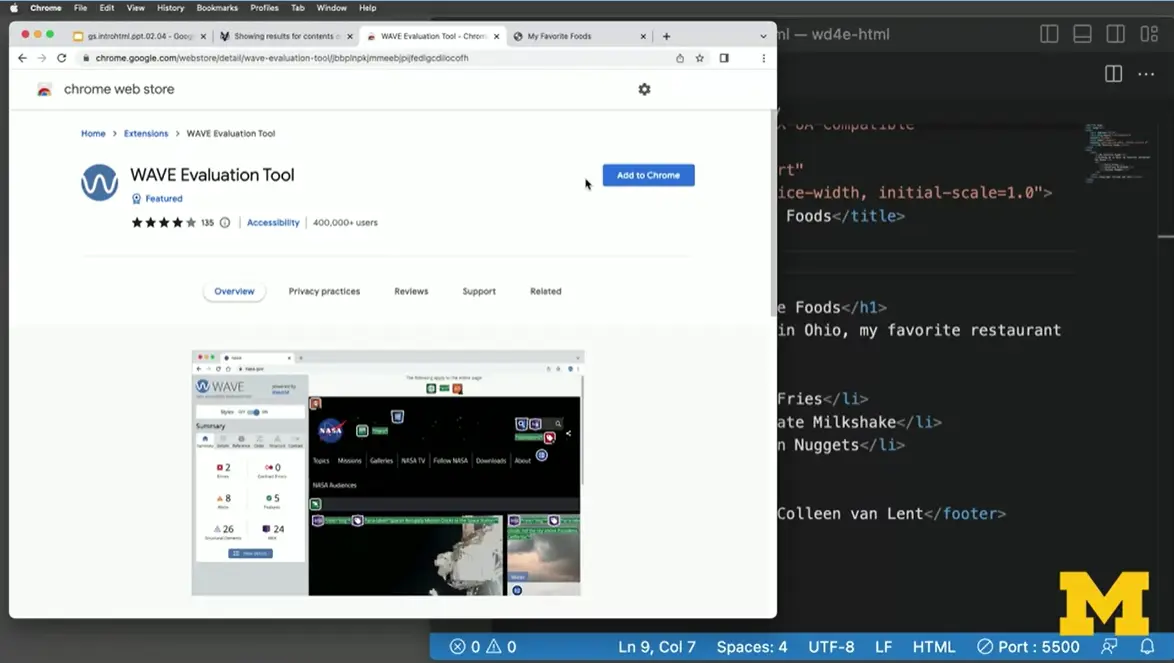

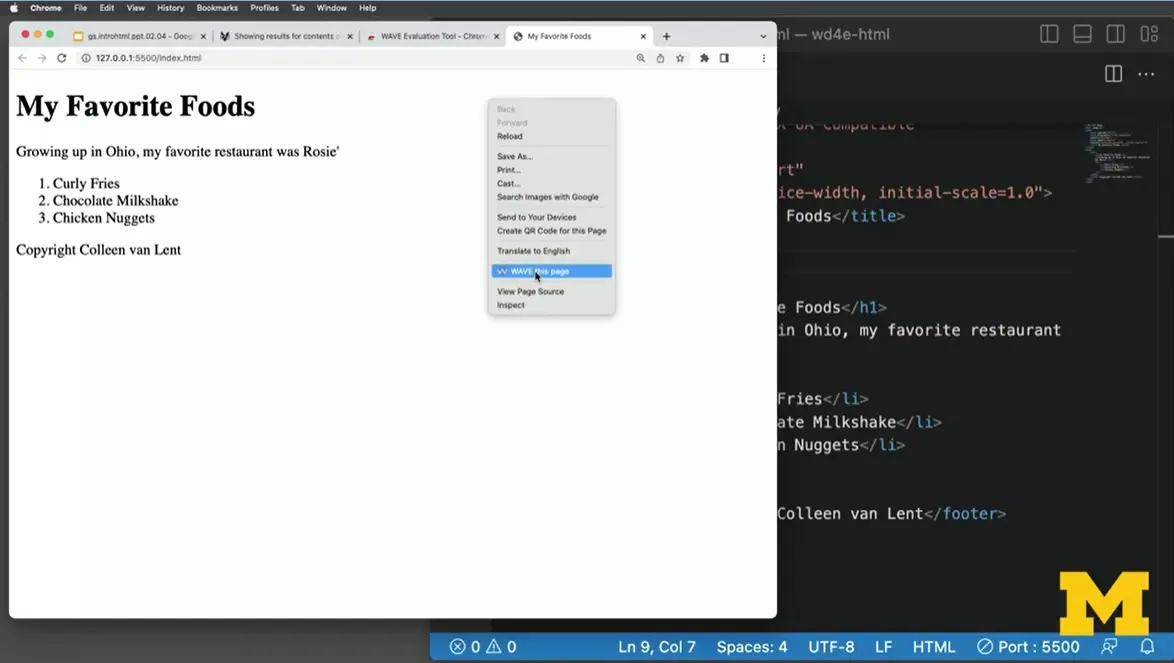

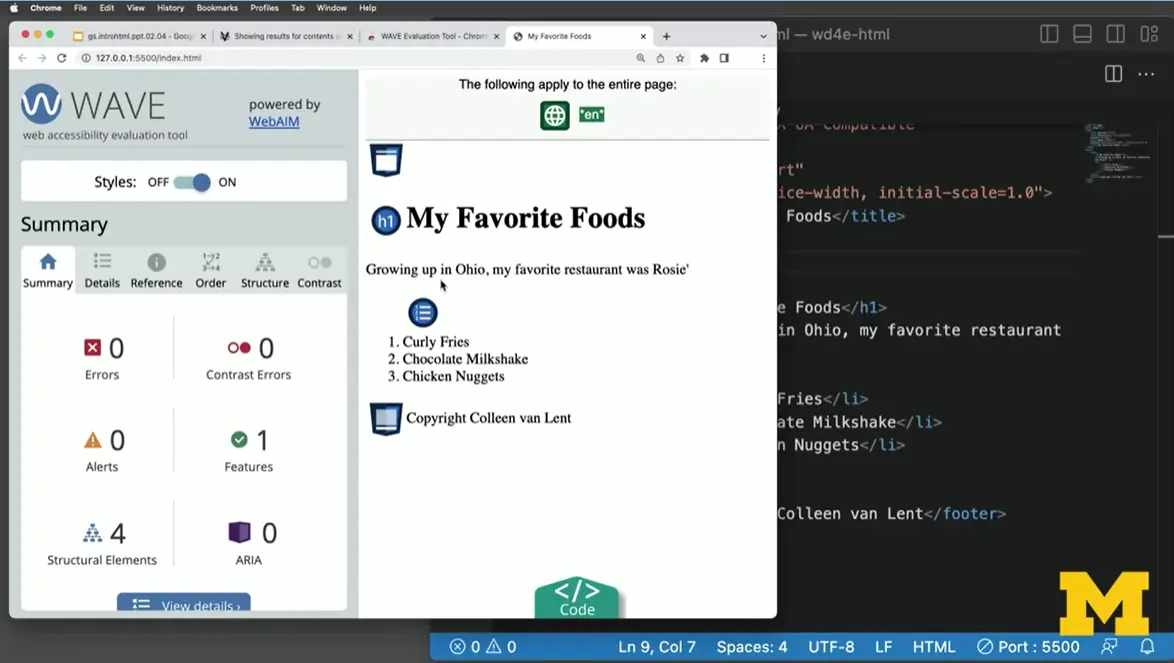

2.04 Template Page in Visual Studio Code

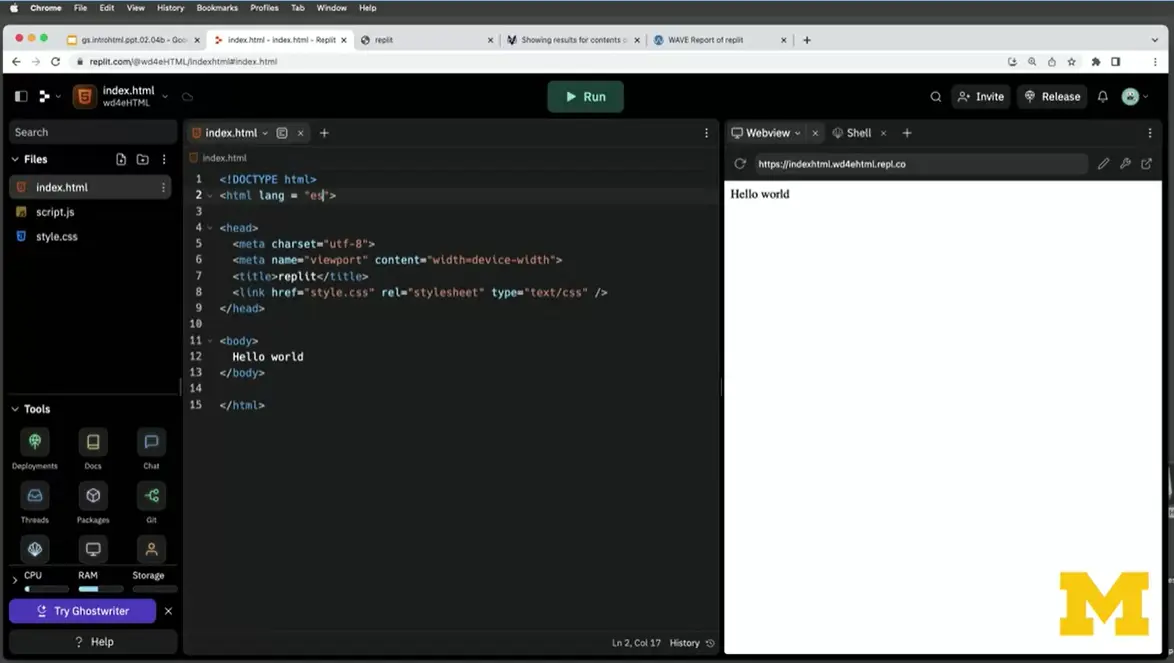

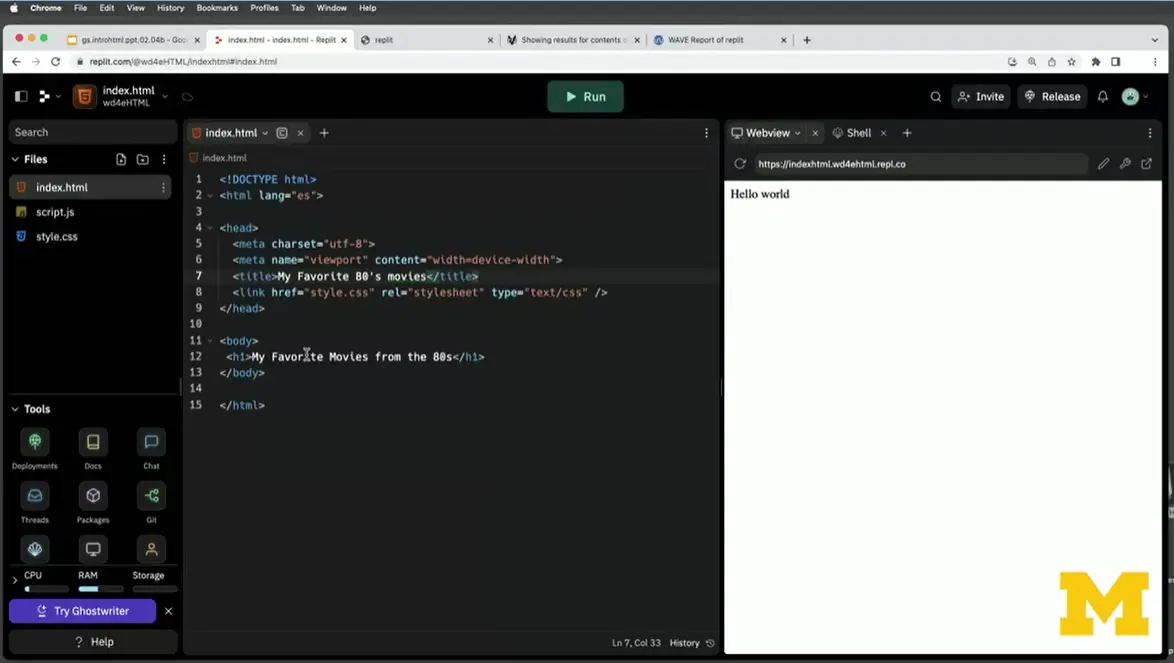

2.05 Template Page in Replit

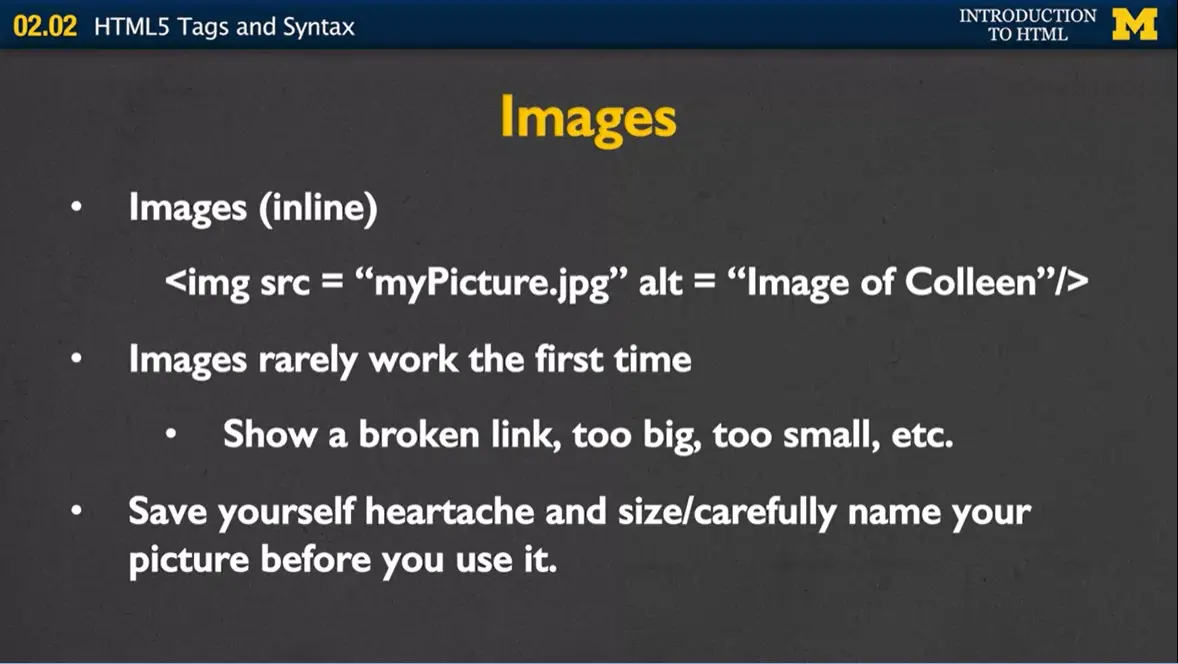

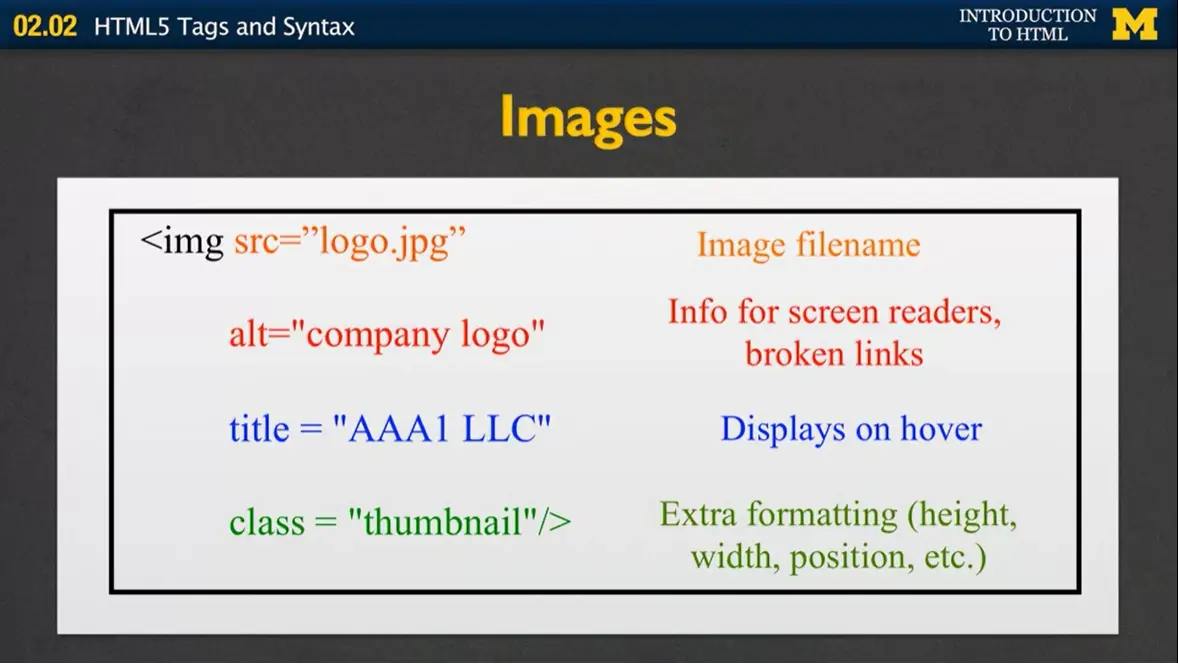

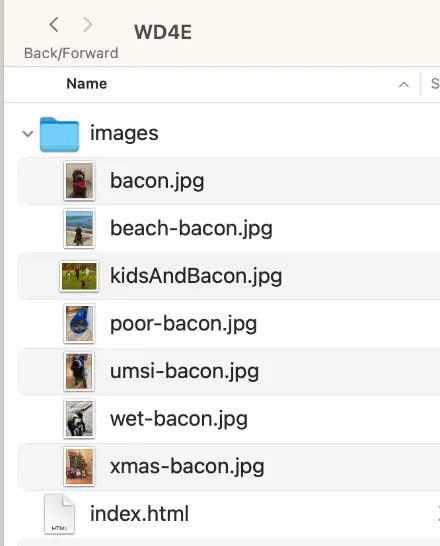

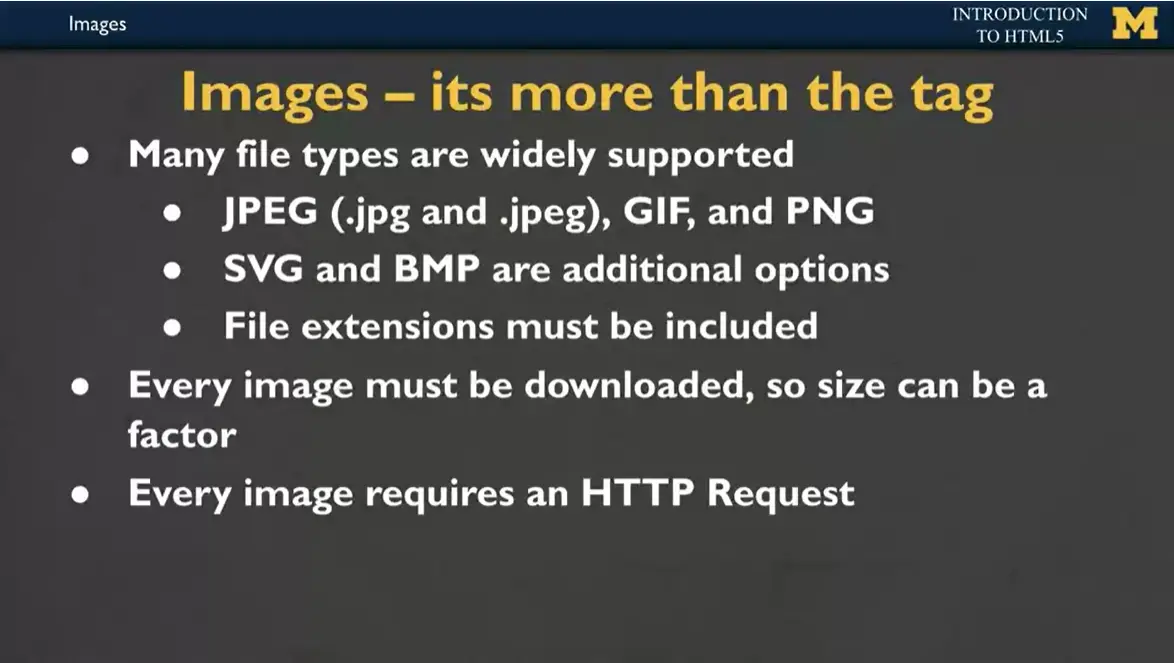

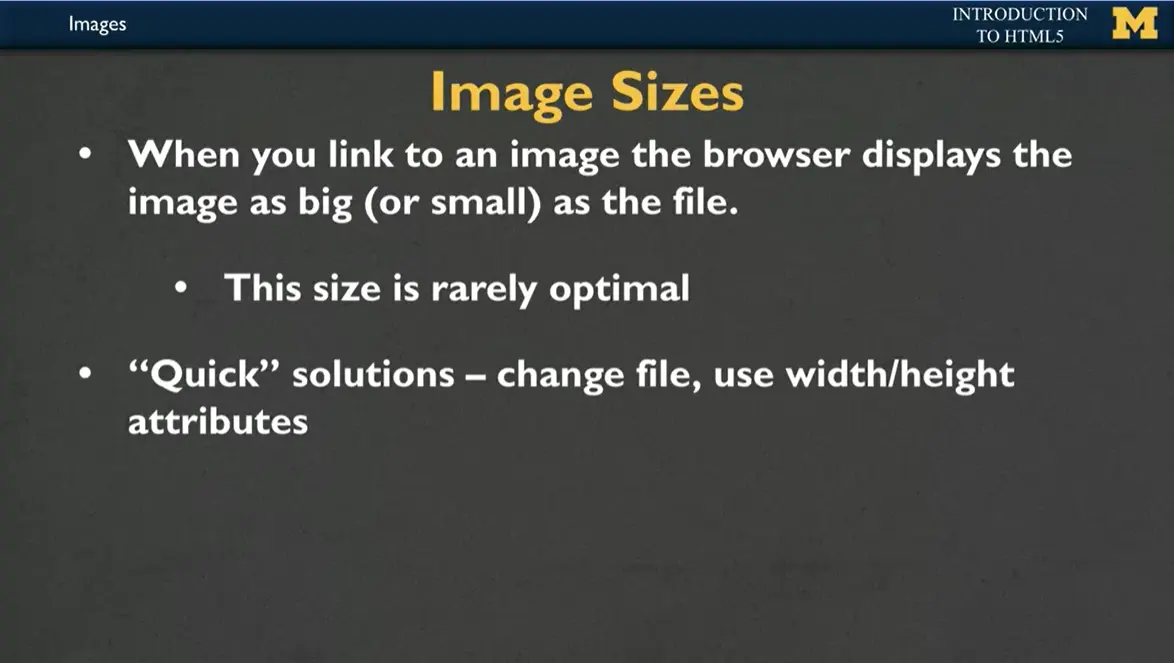

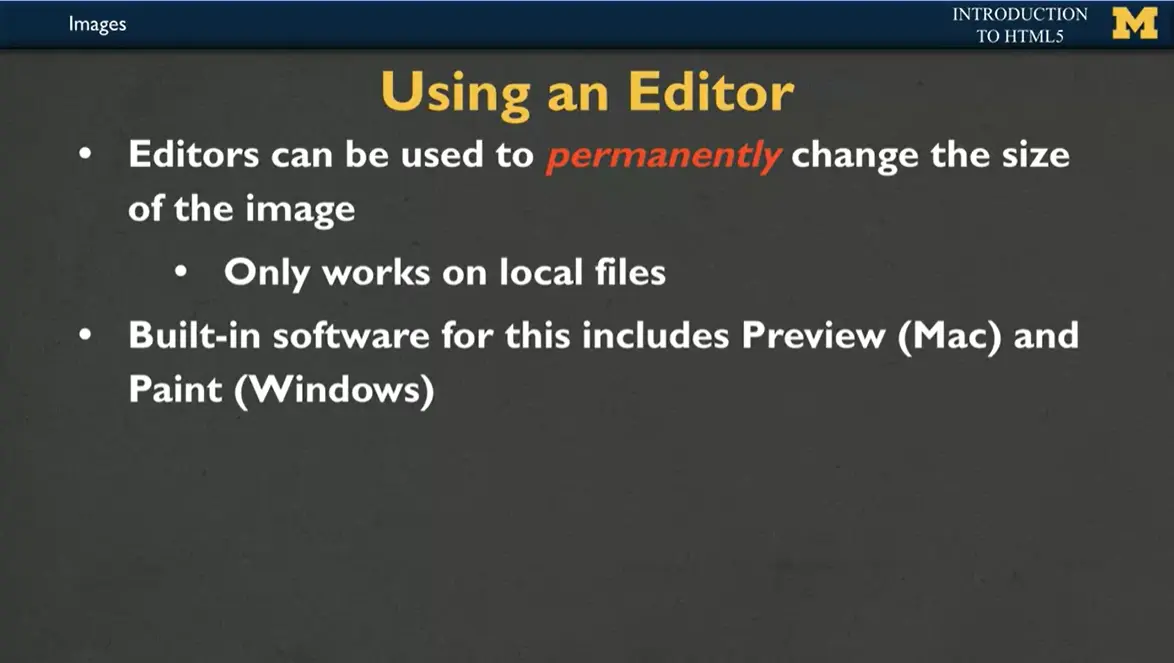

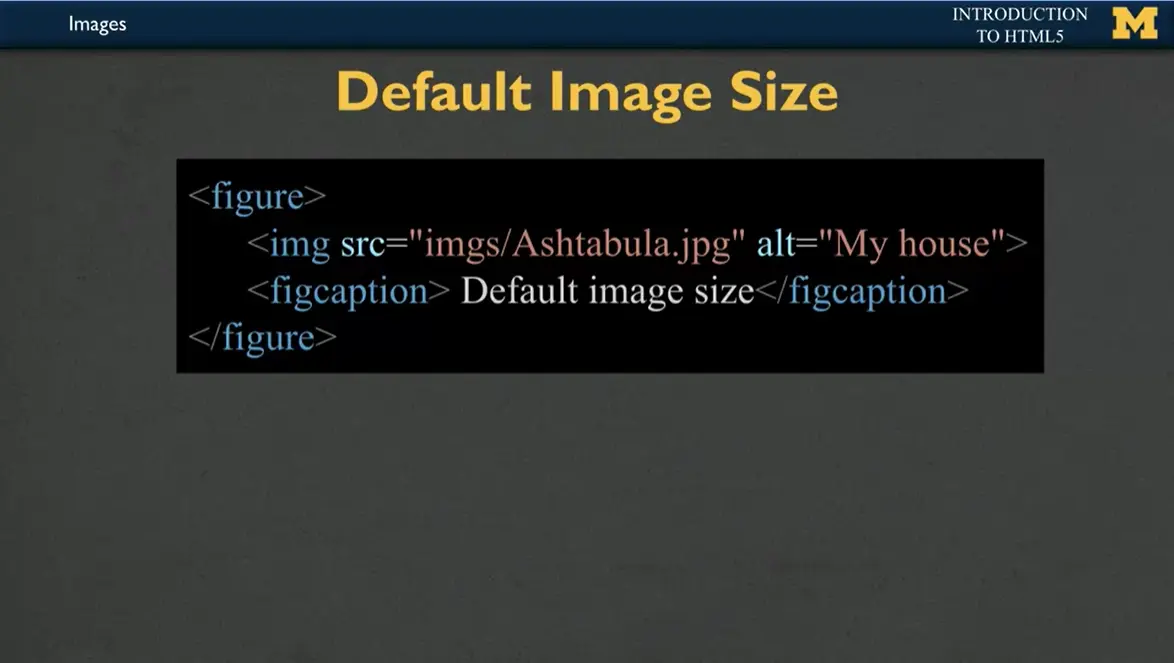

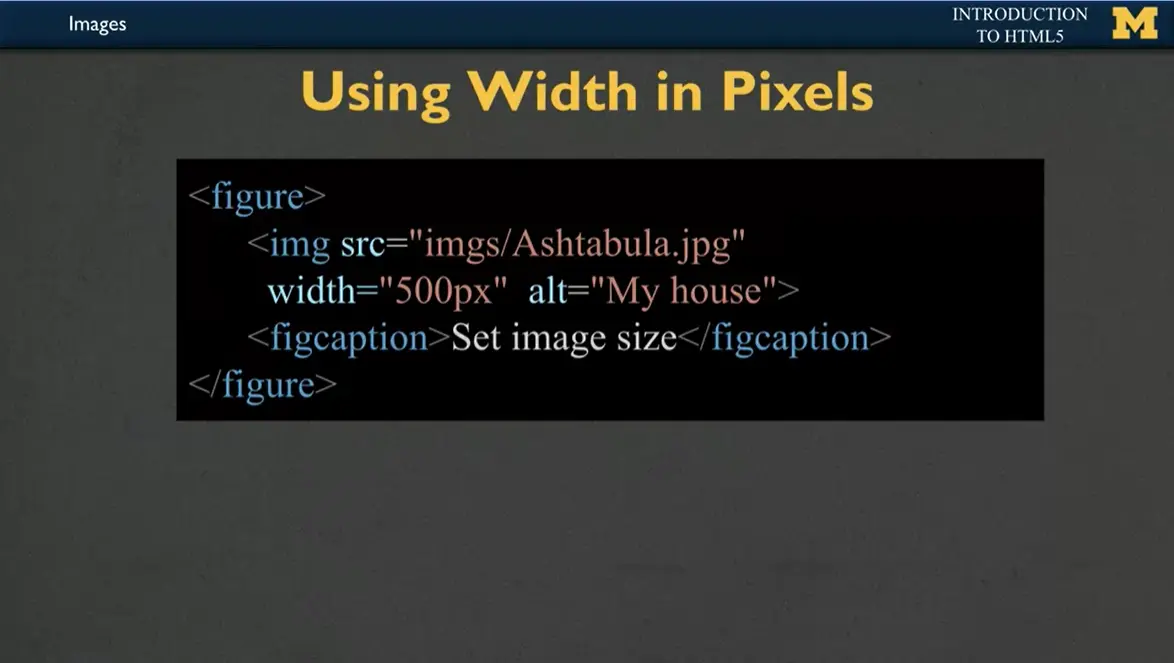

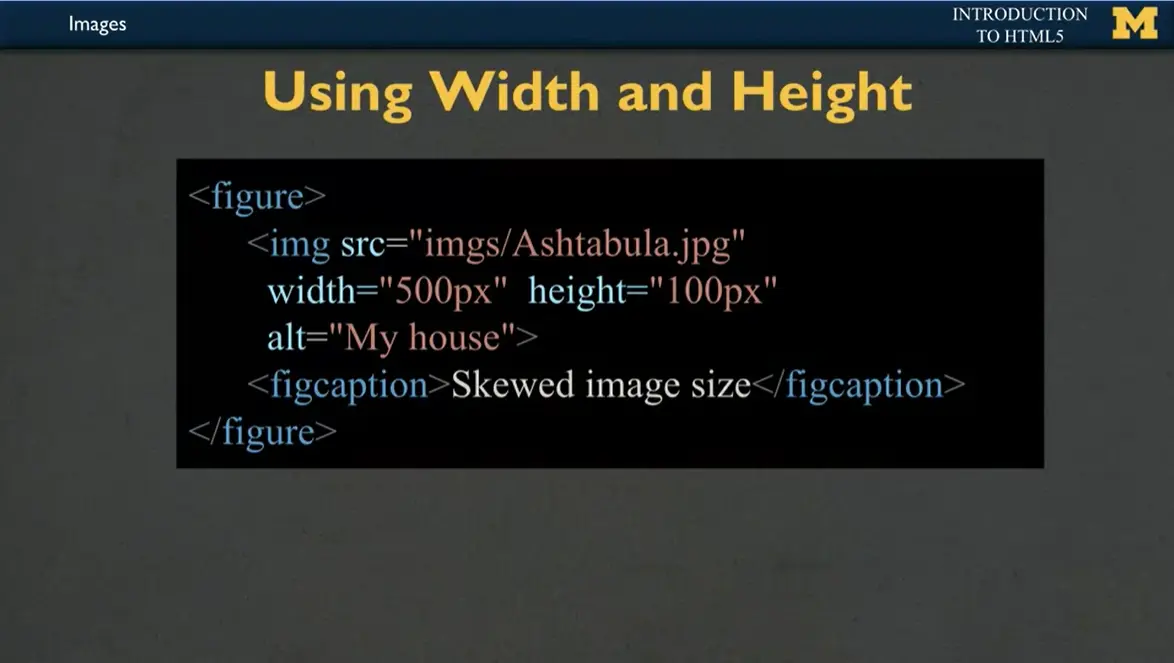

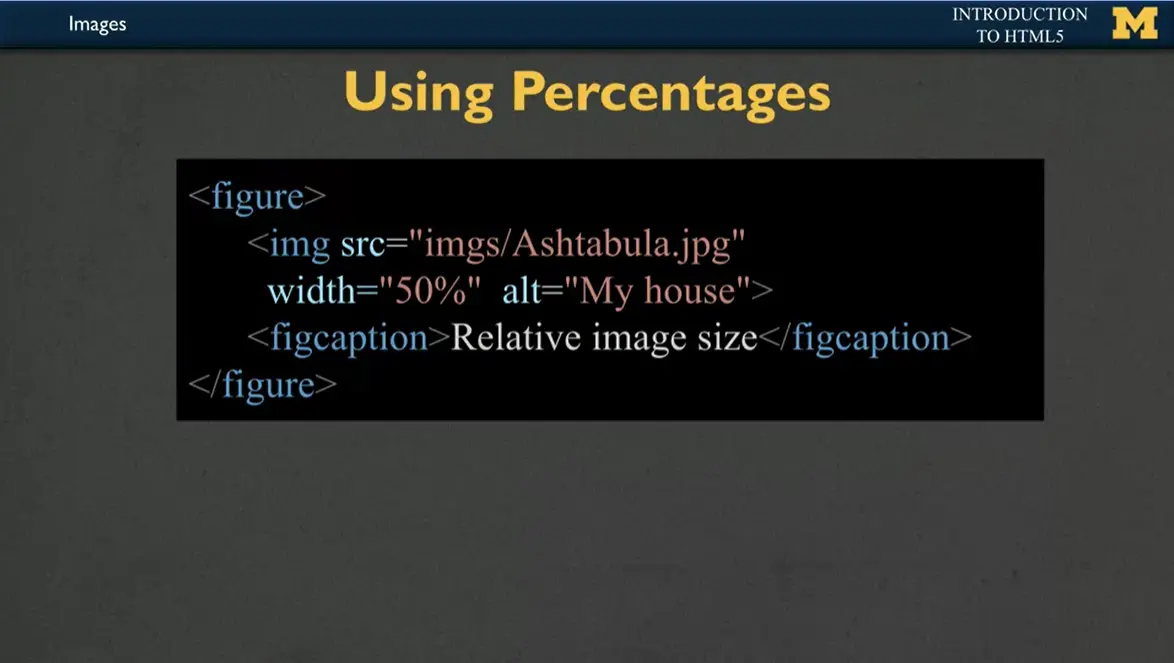

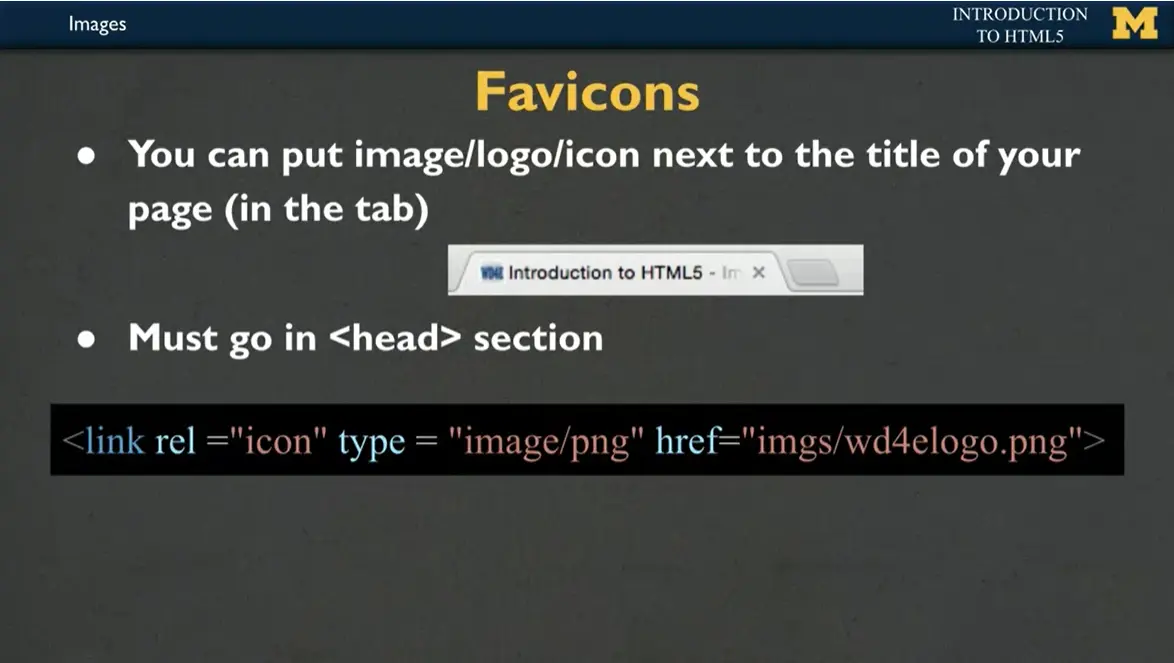

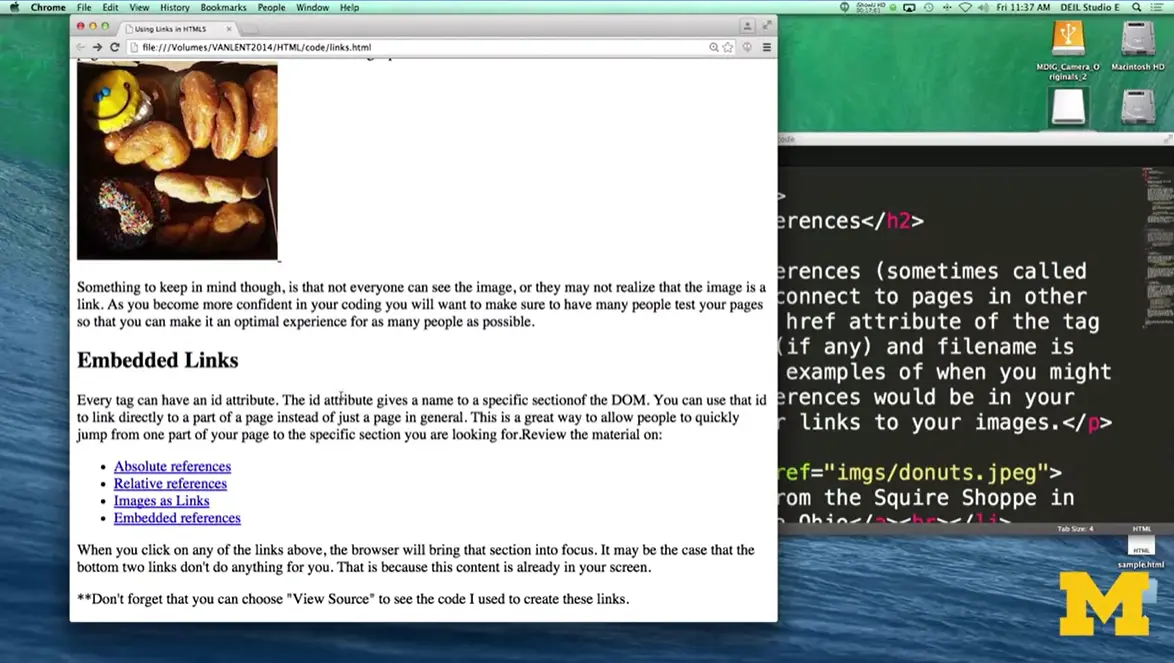

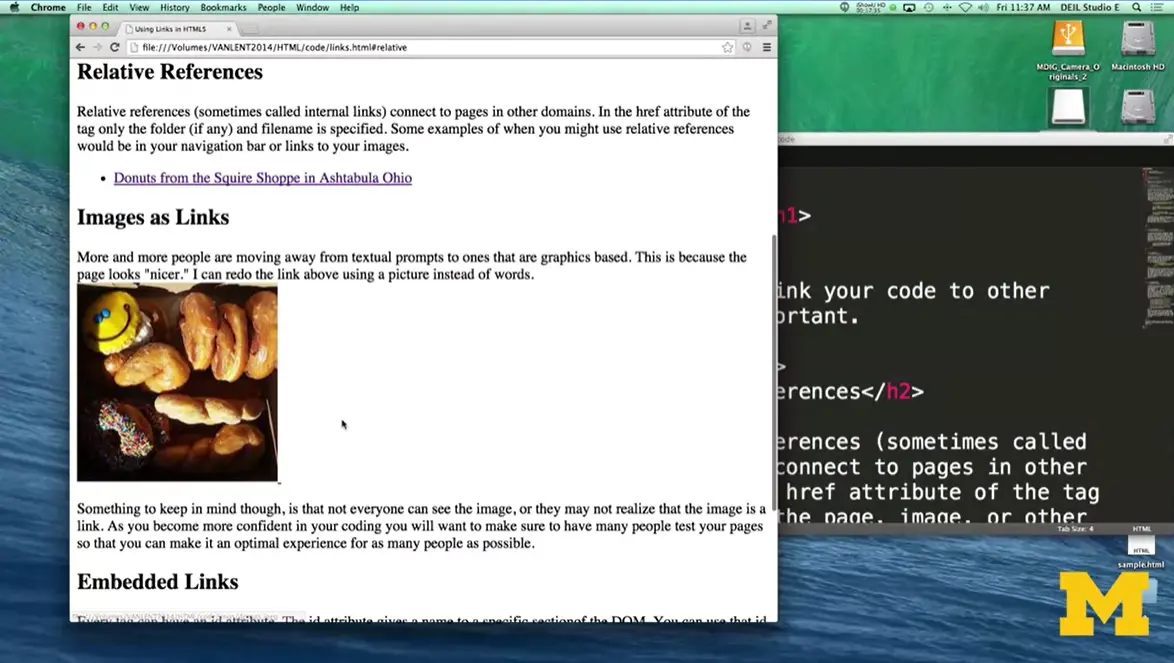

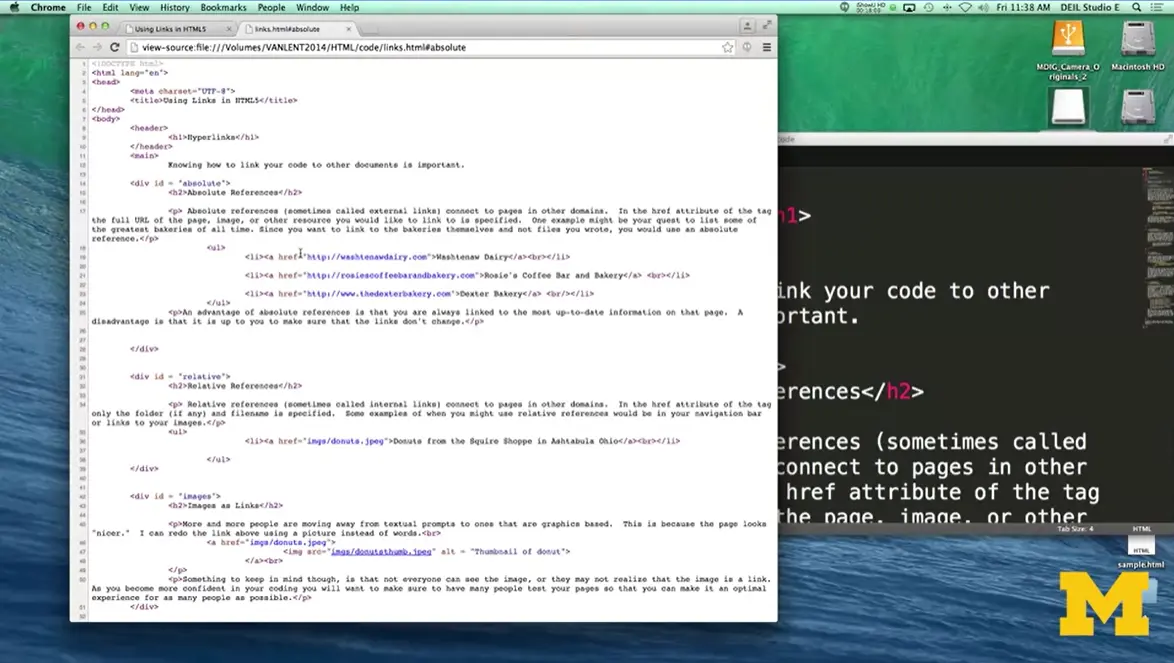

2.06 Images

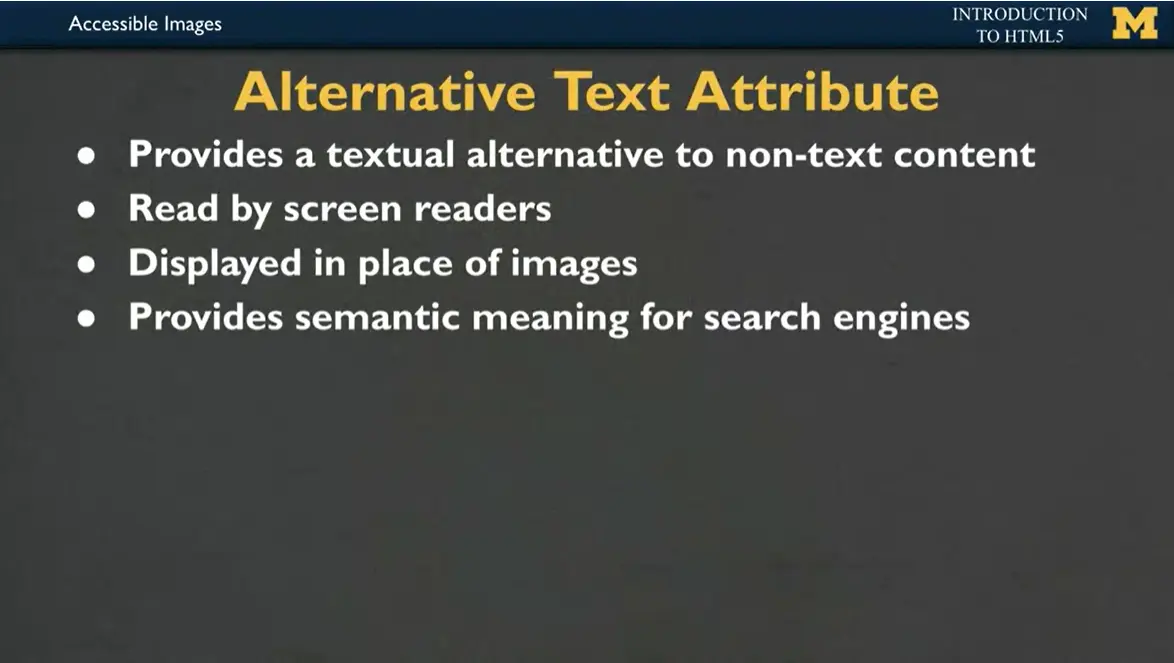

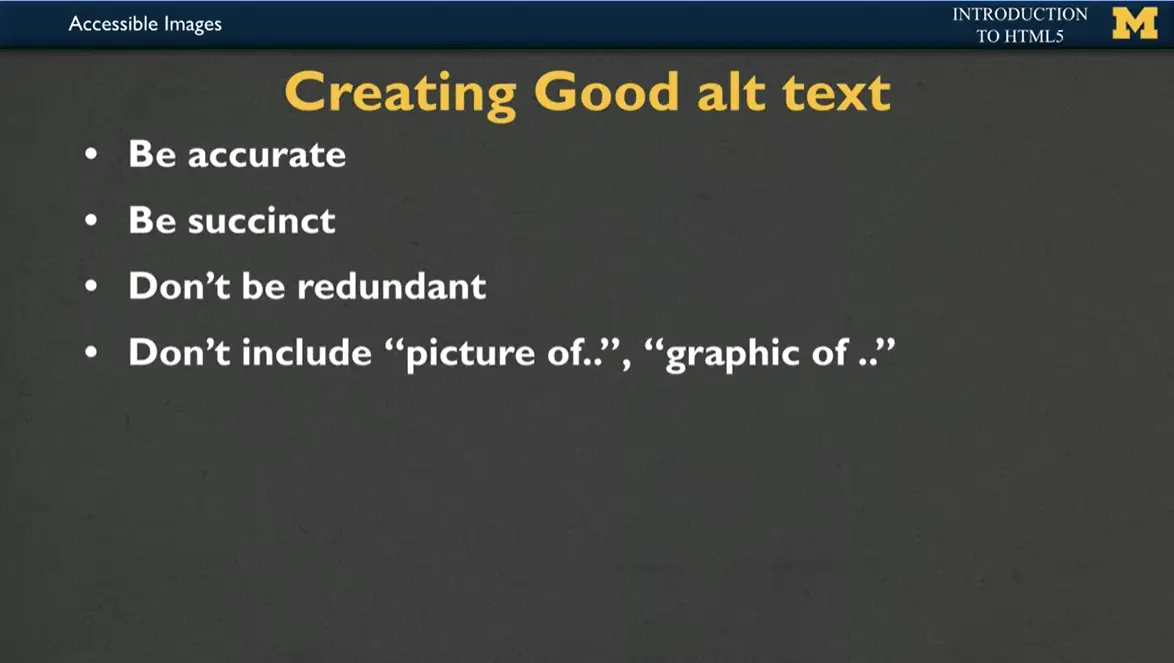

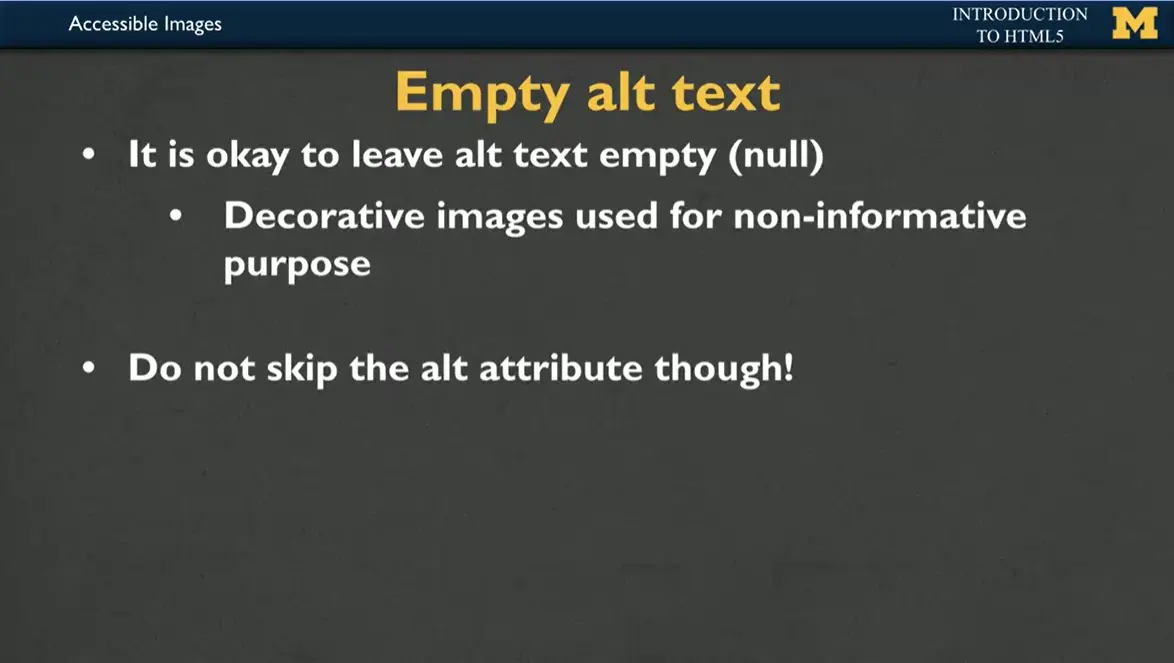

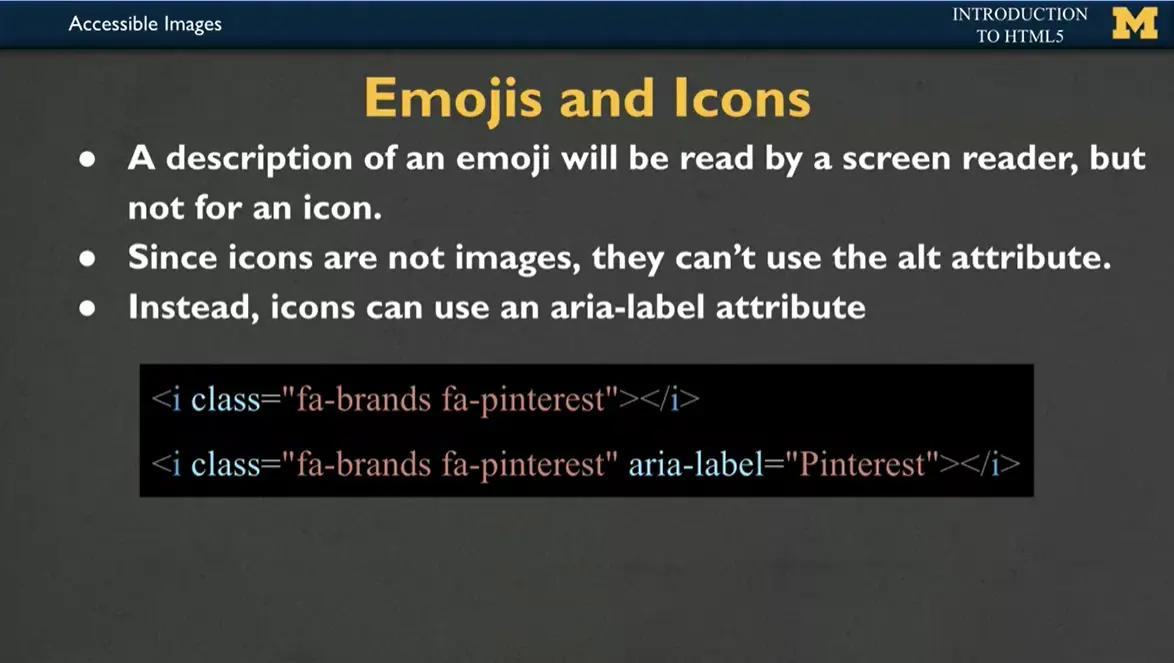

2.07 Accessible Images

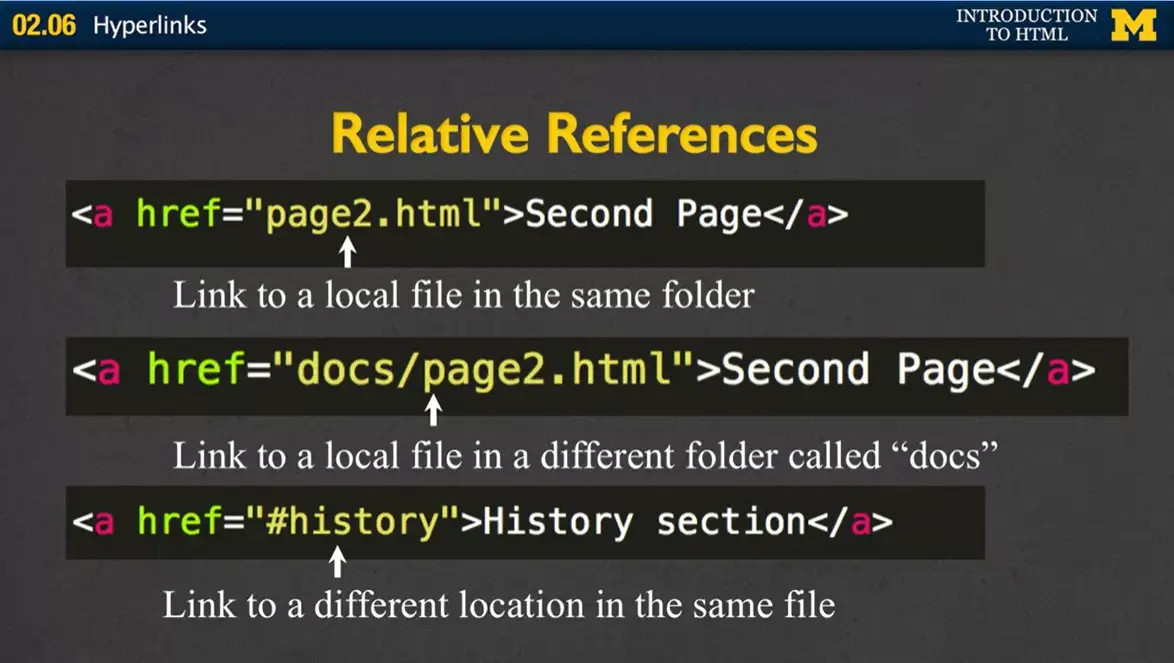

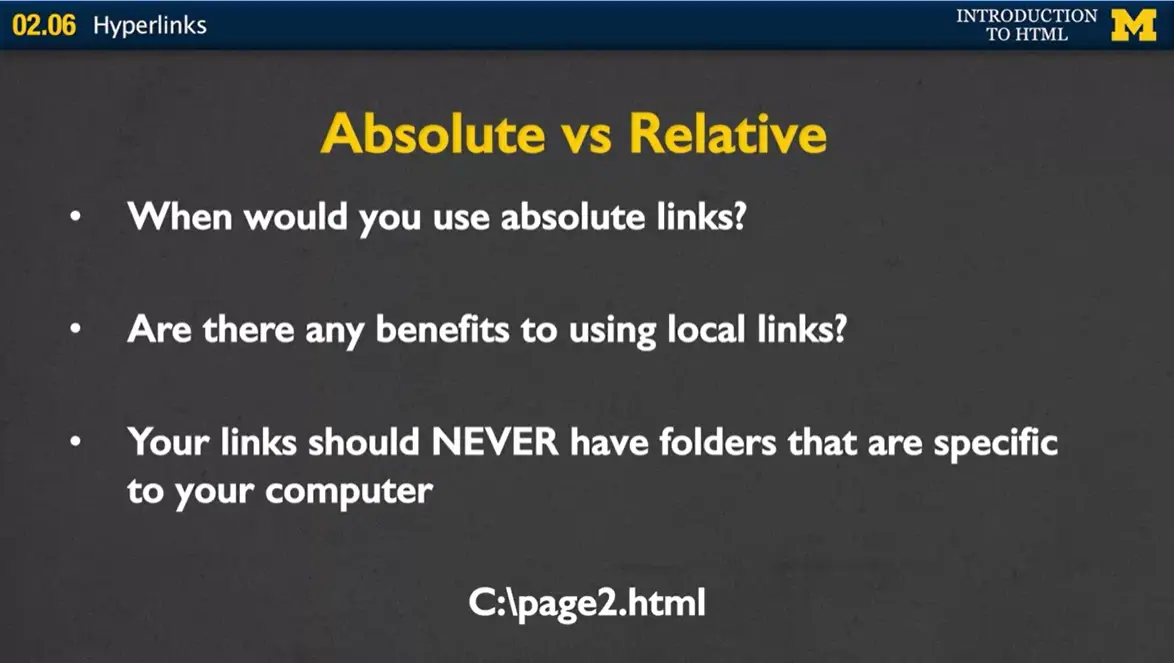

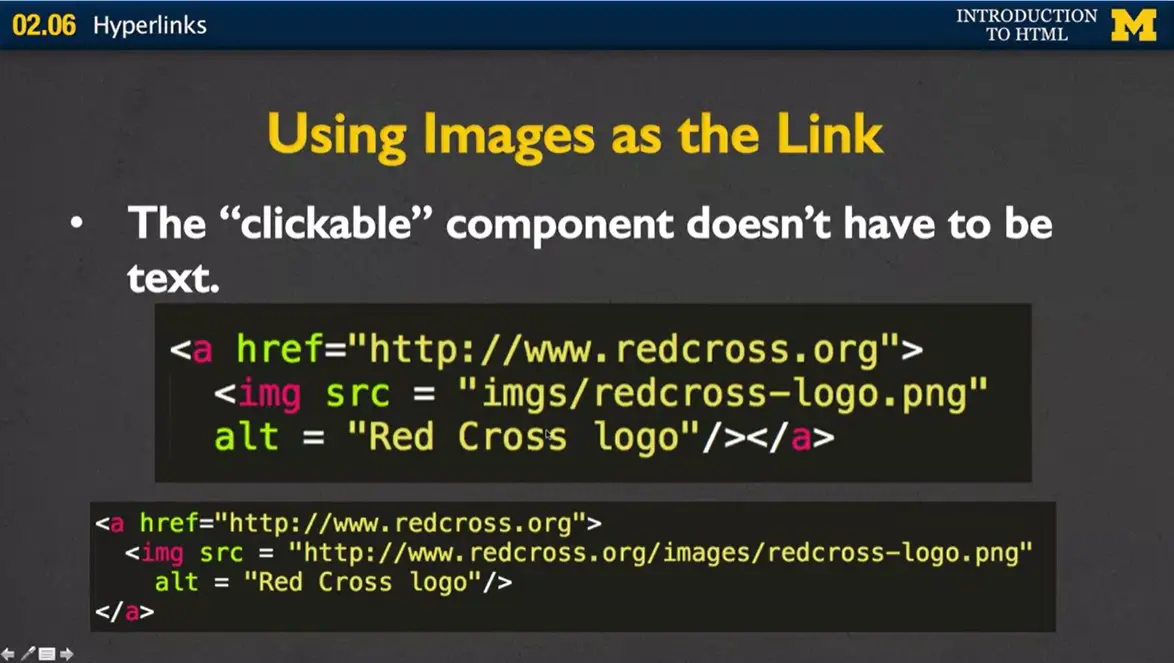

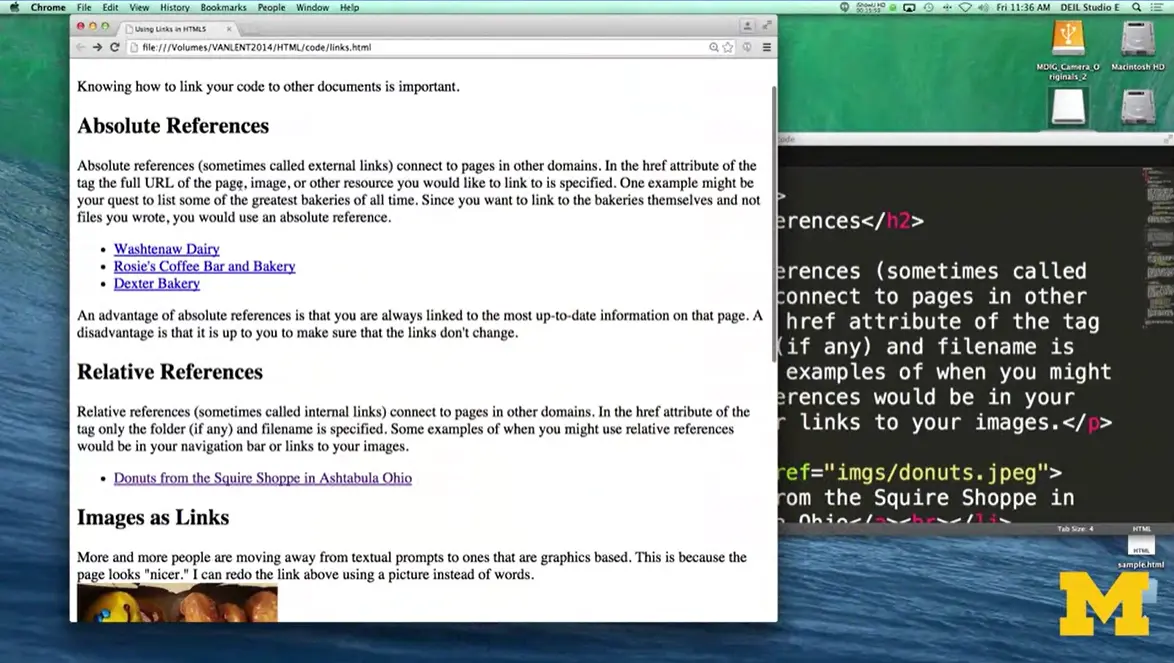

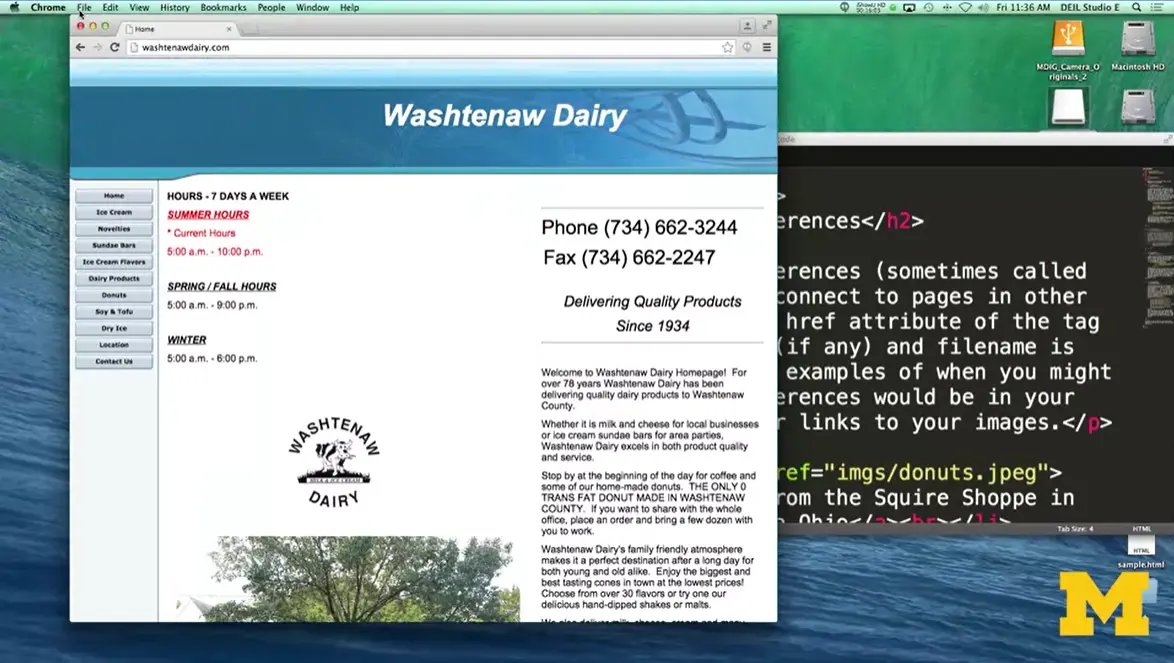

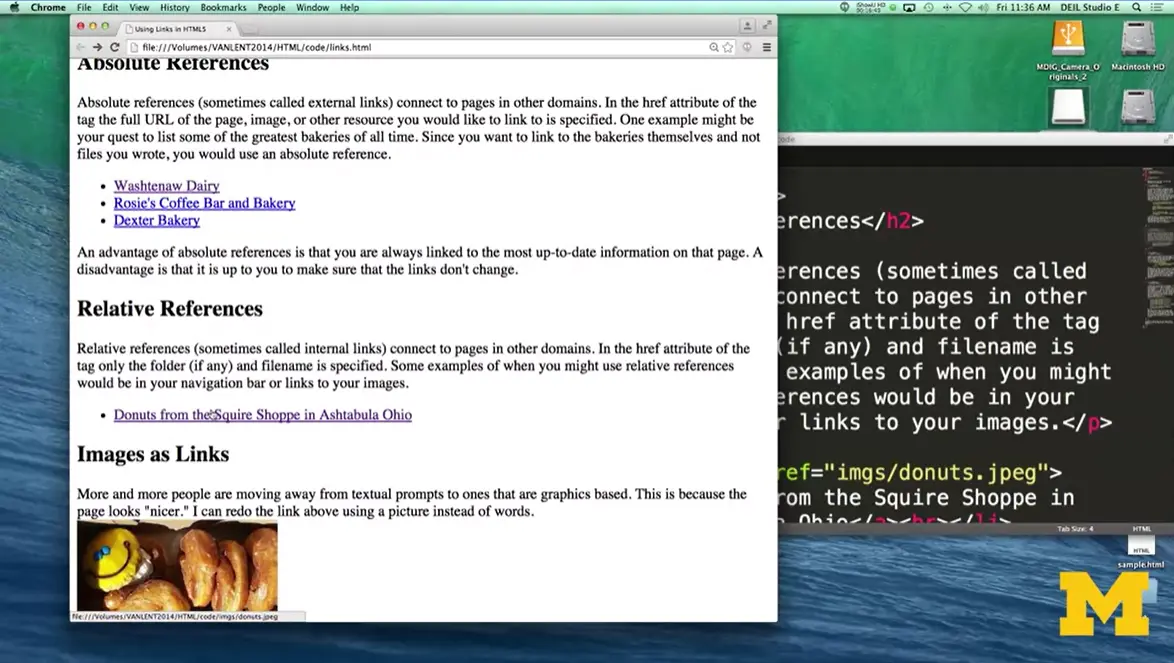

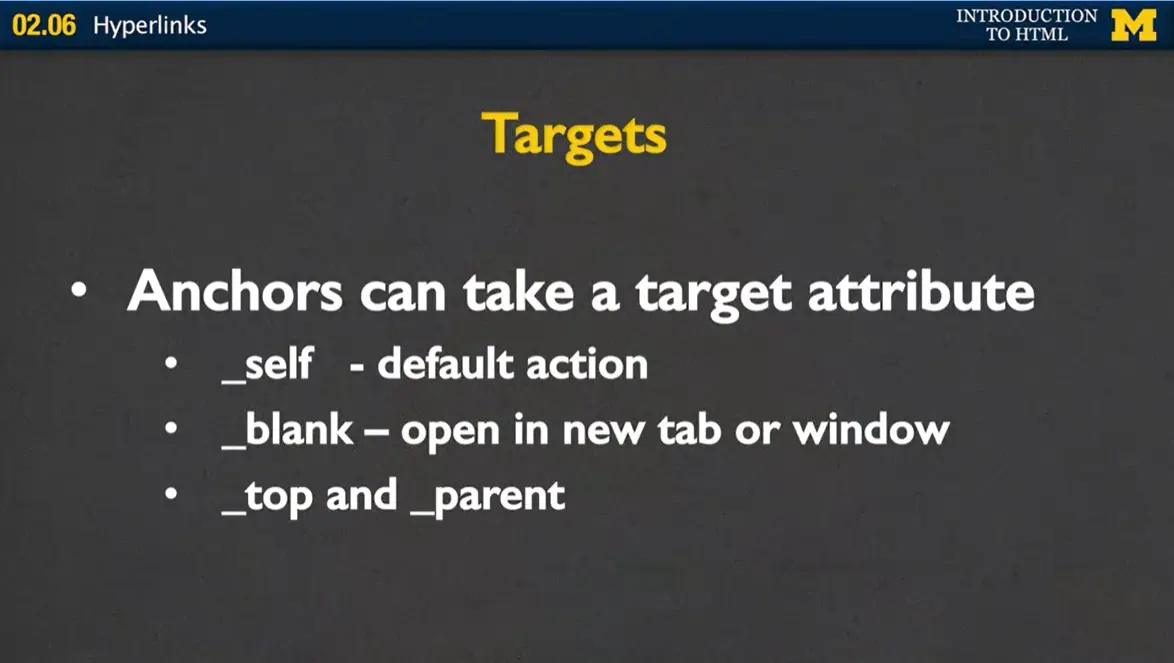

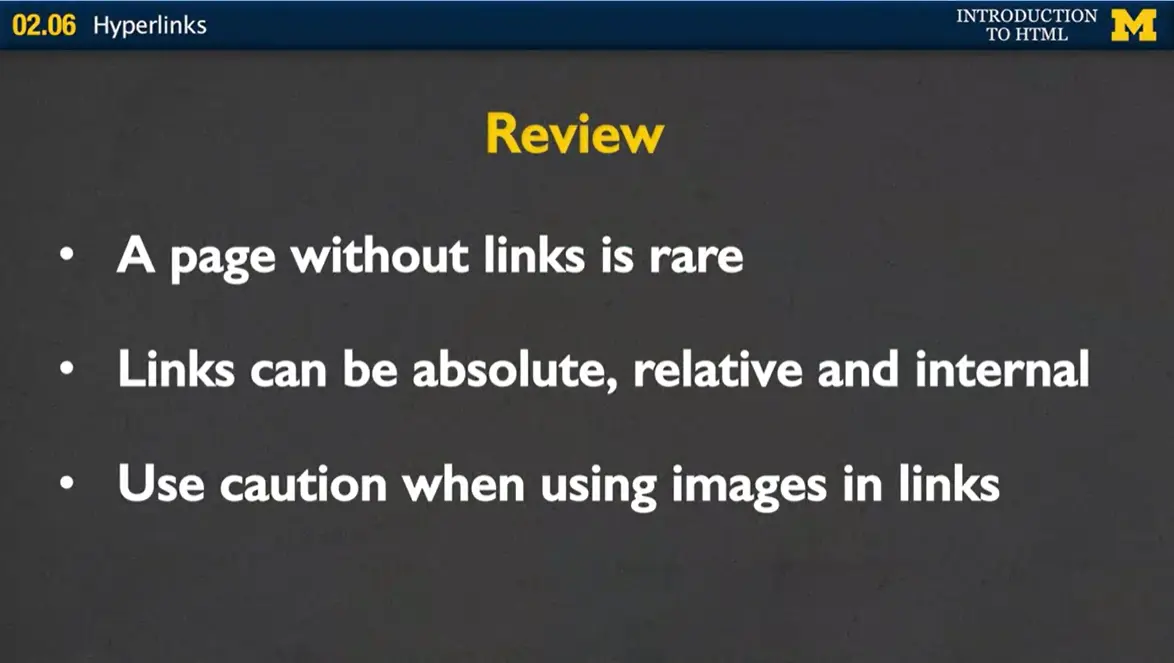

2.08 Hyperlinks

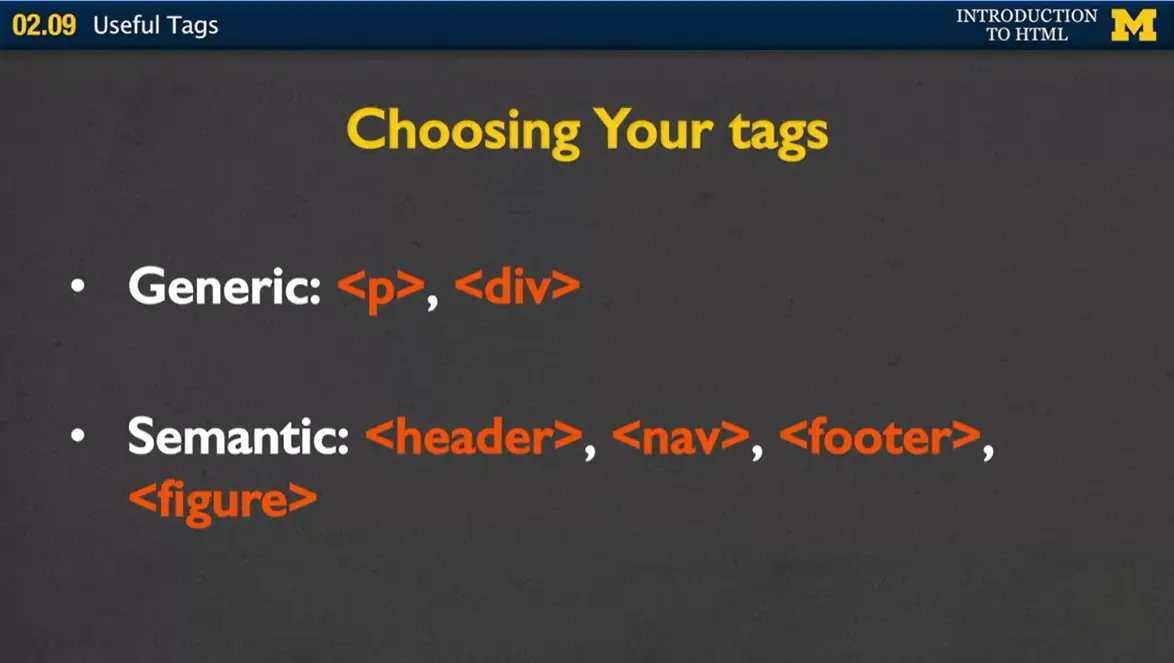

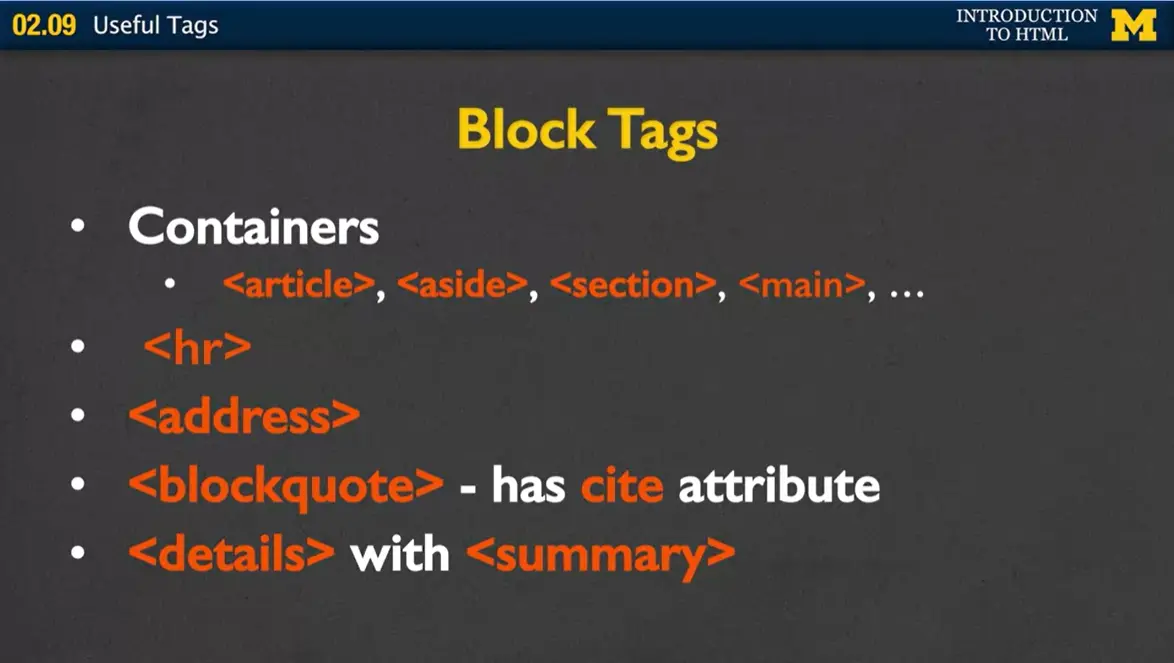

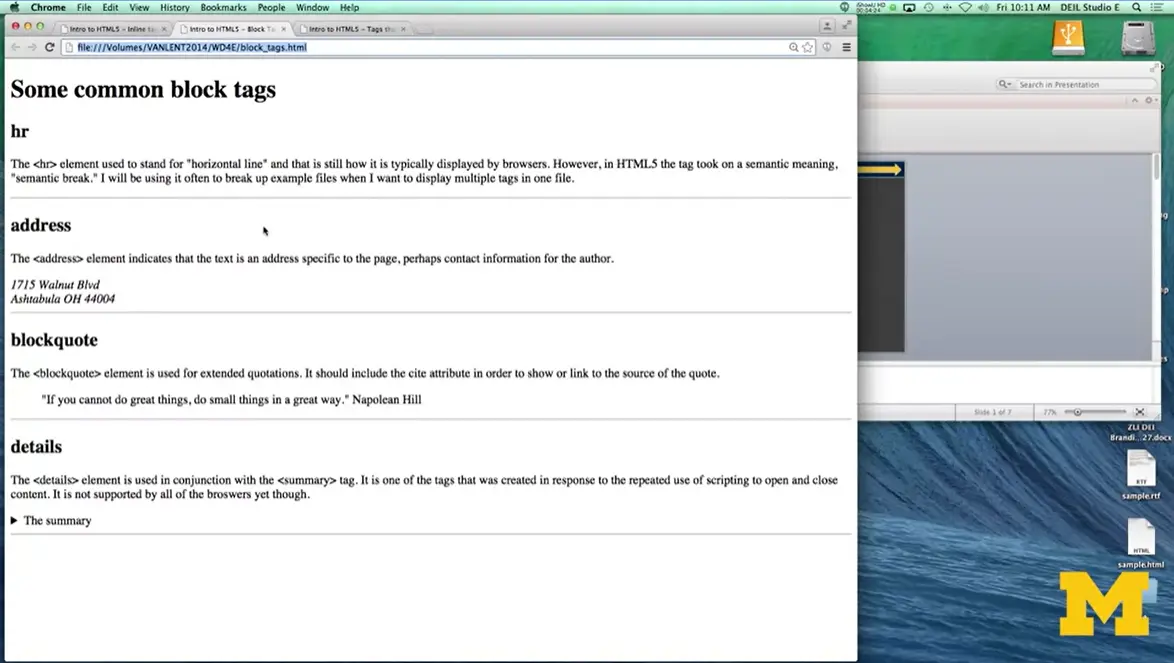

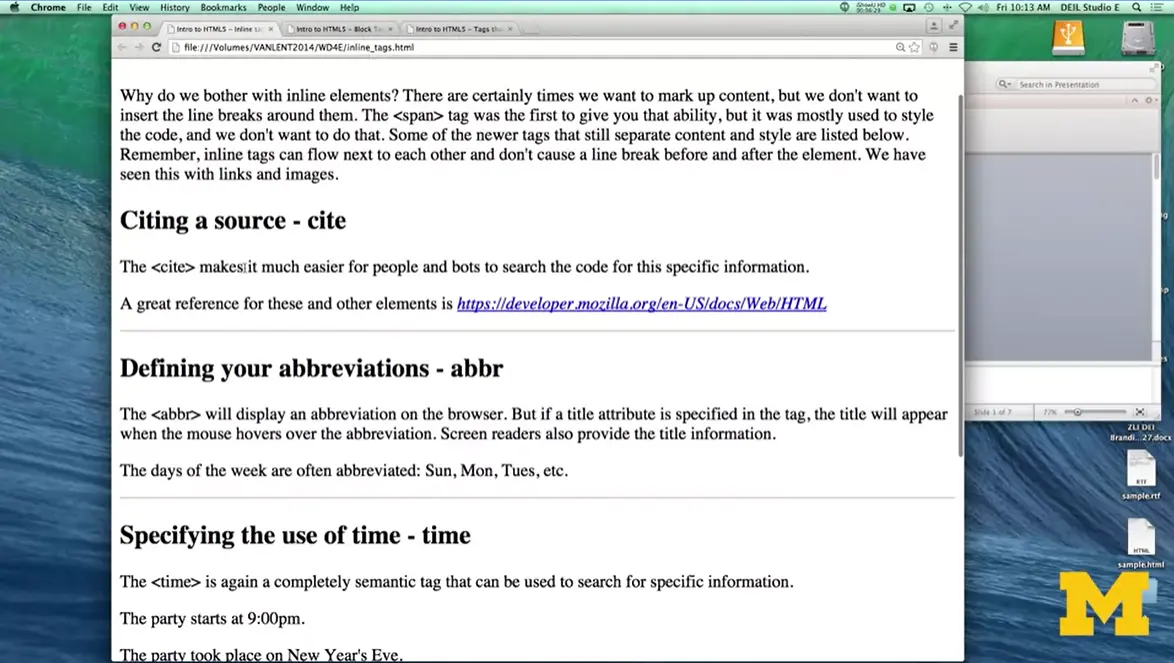

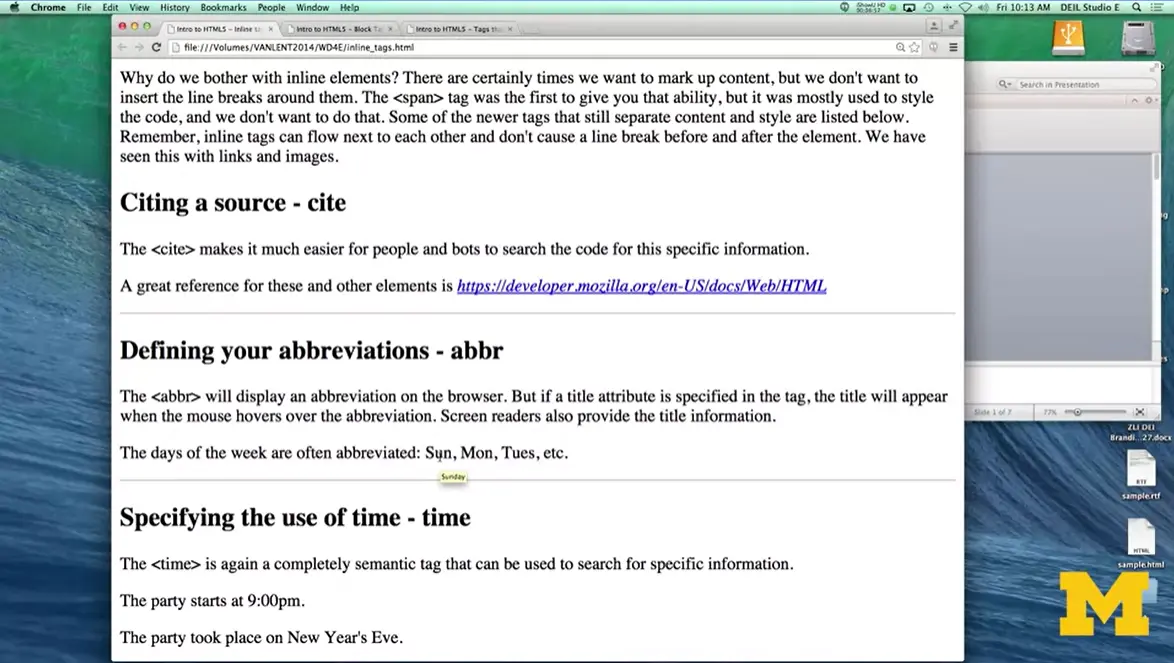

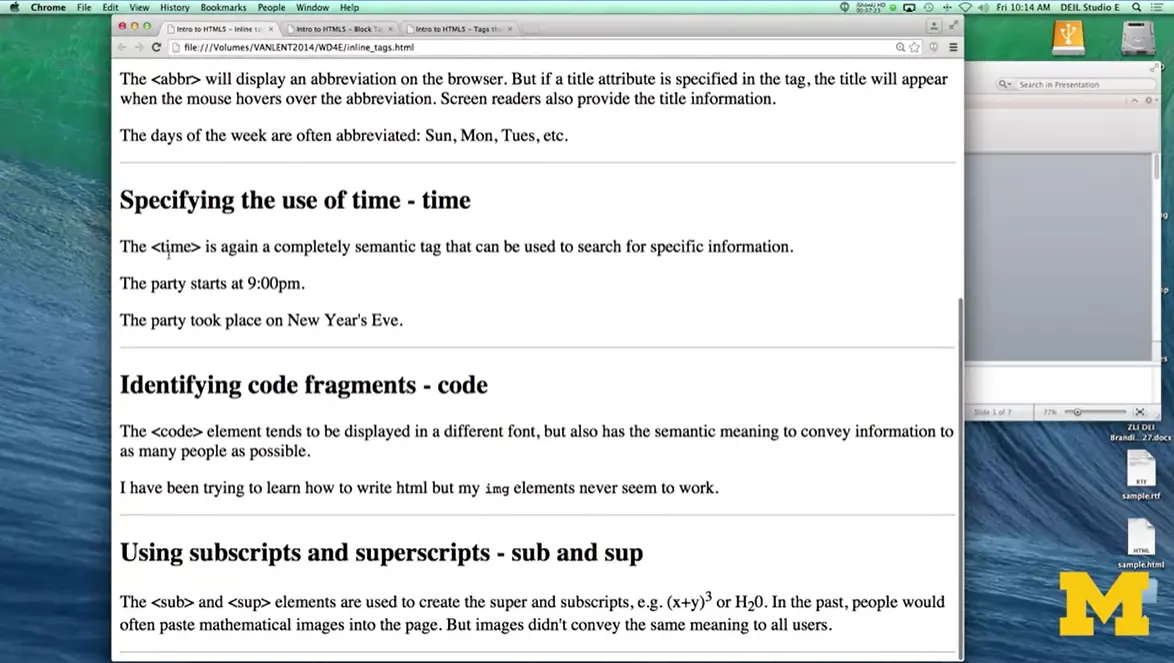

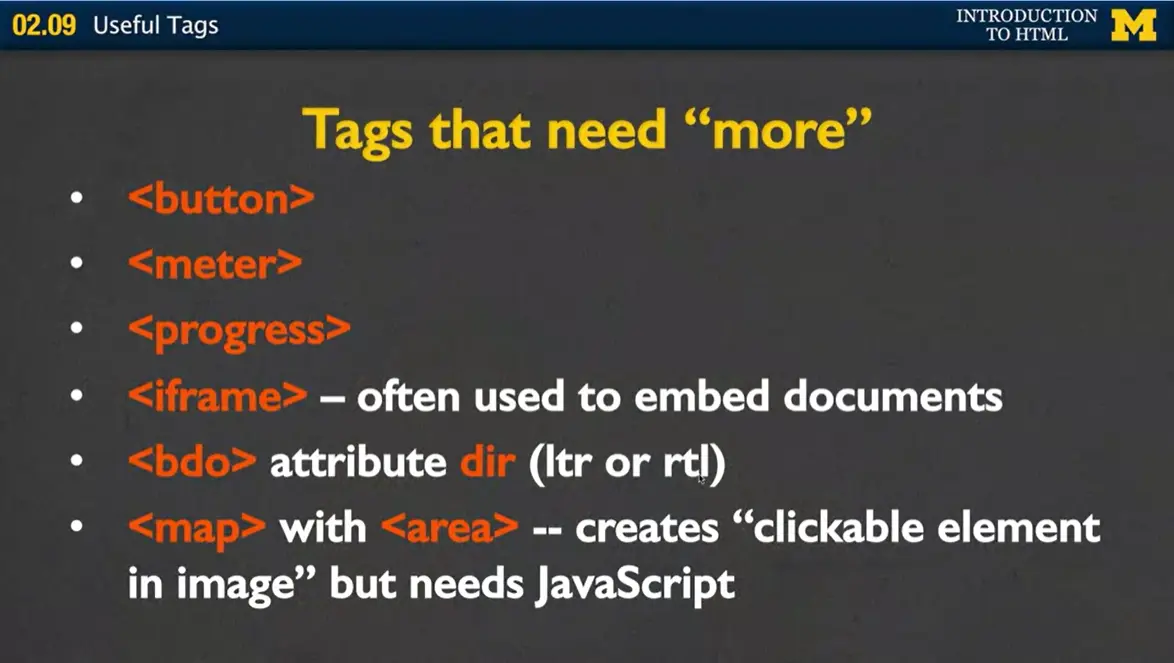

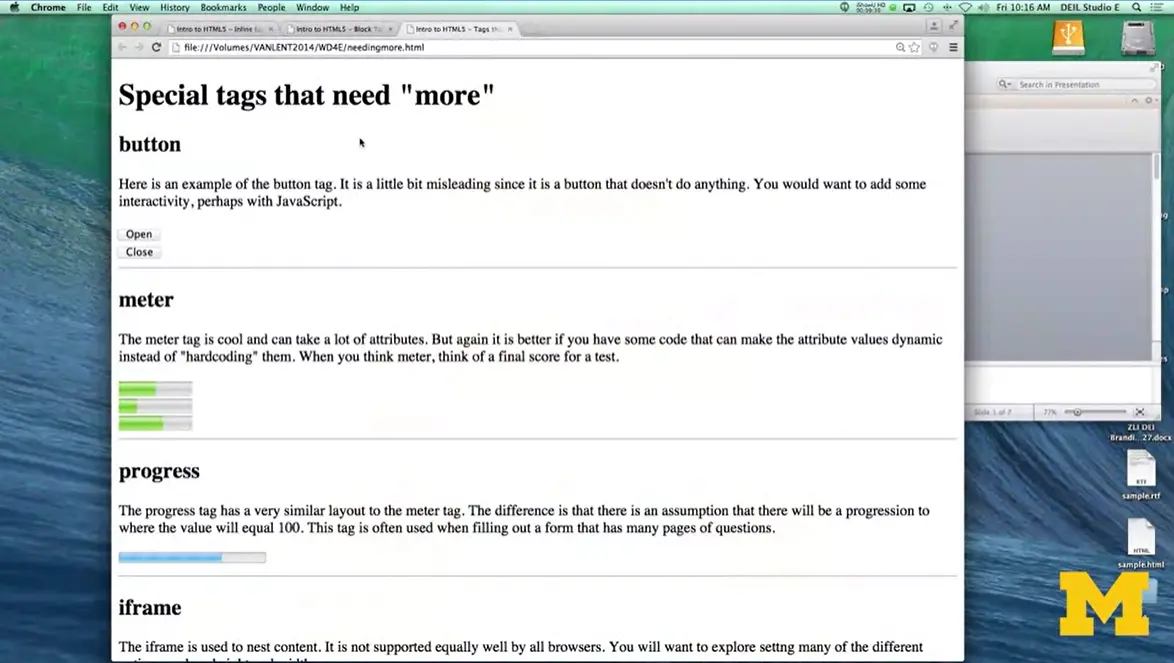

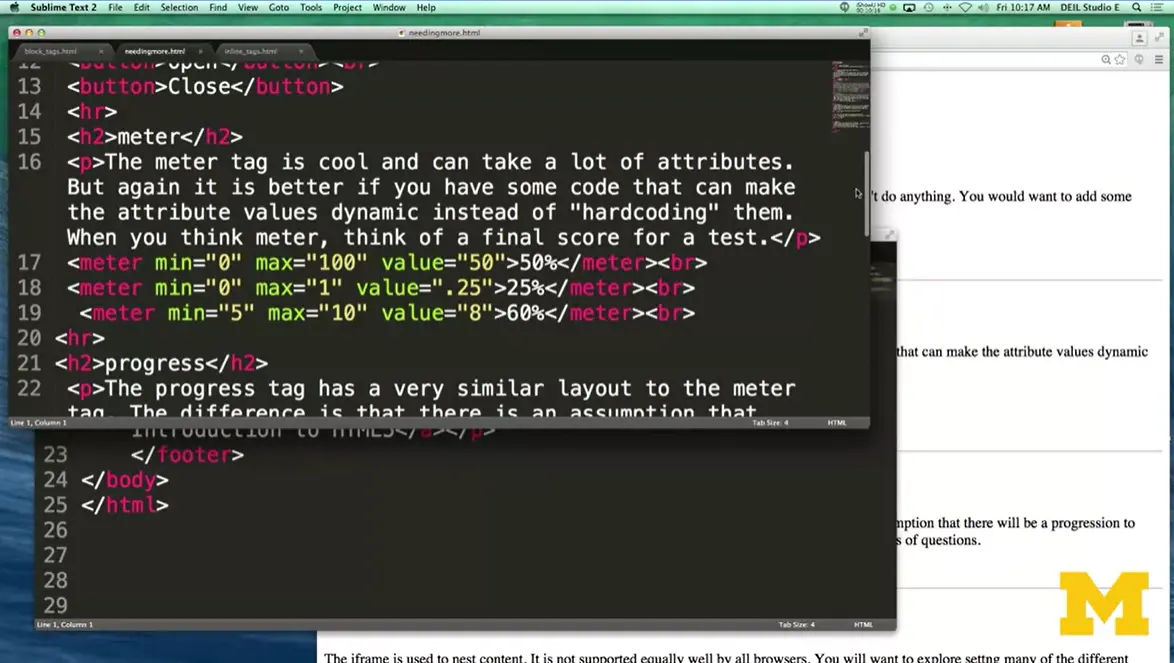

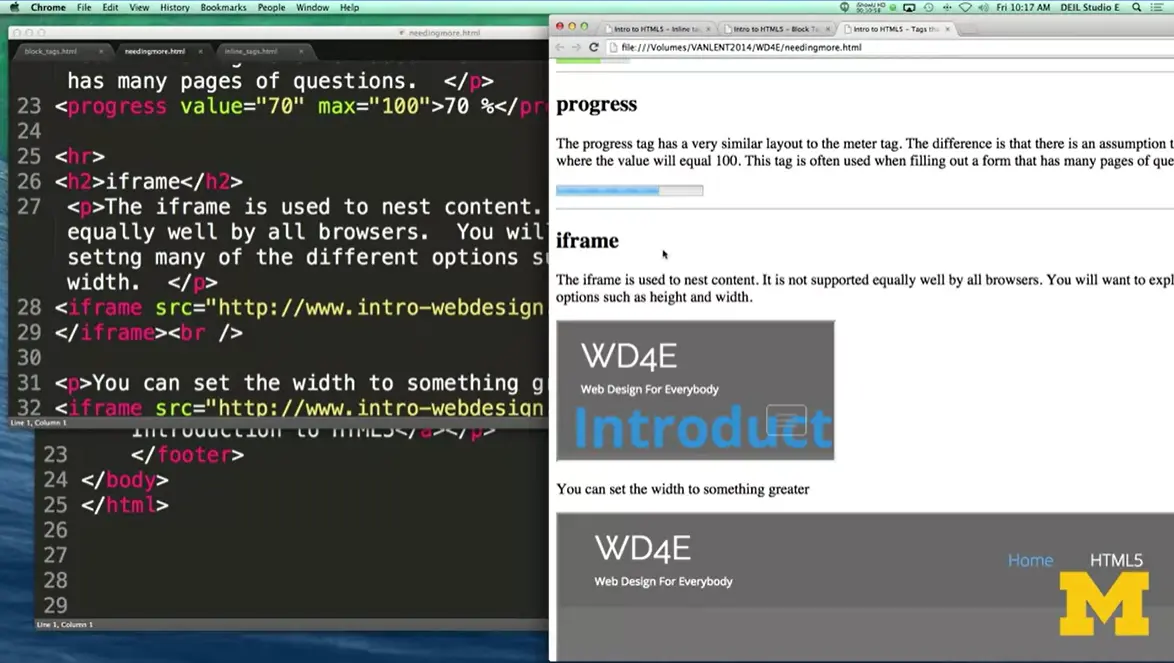

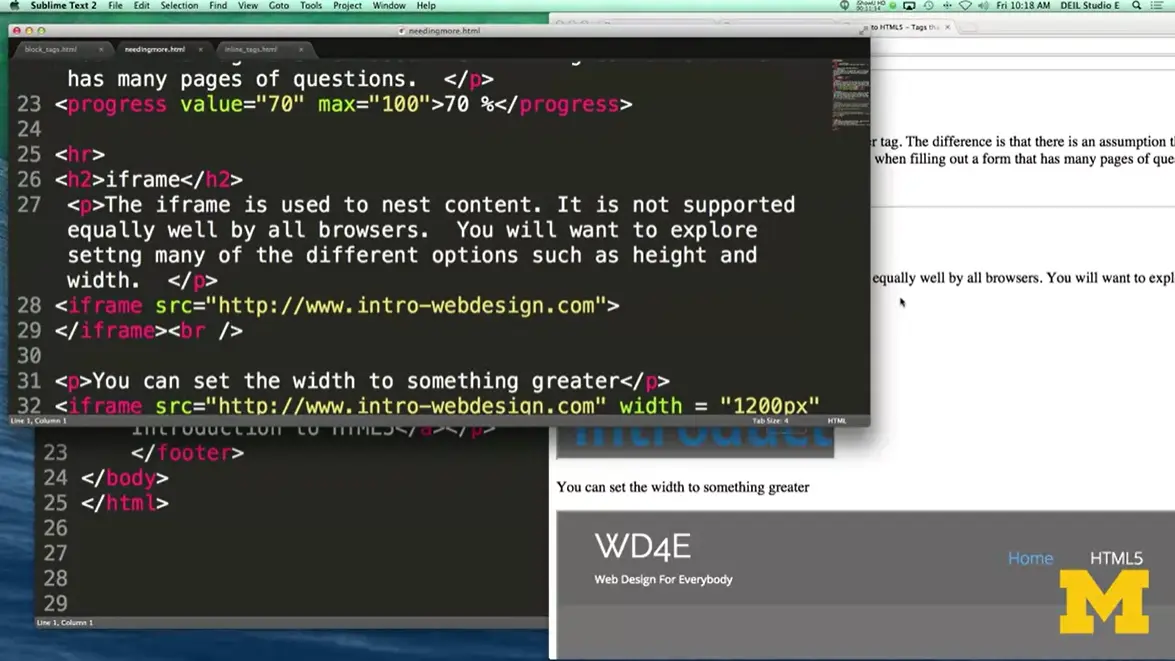

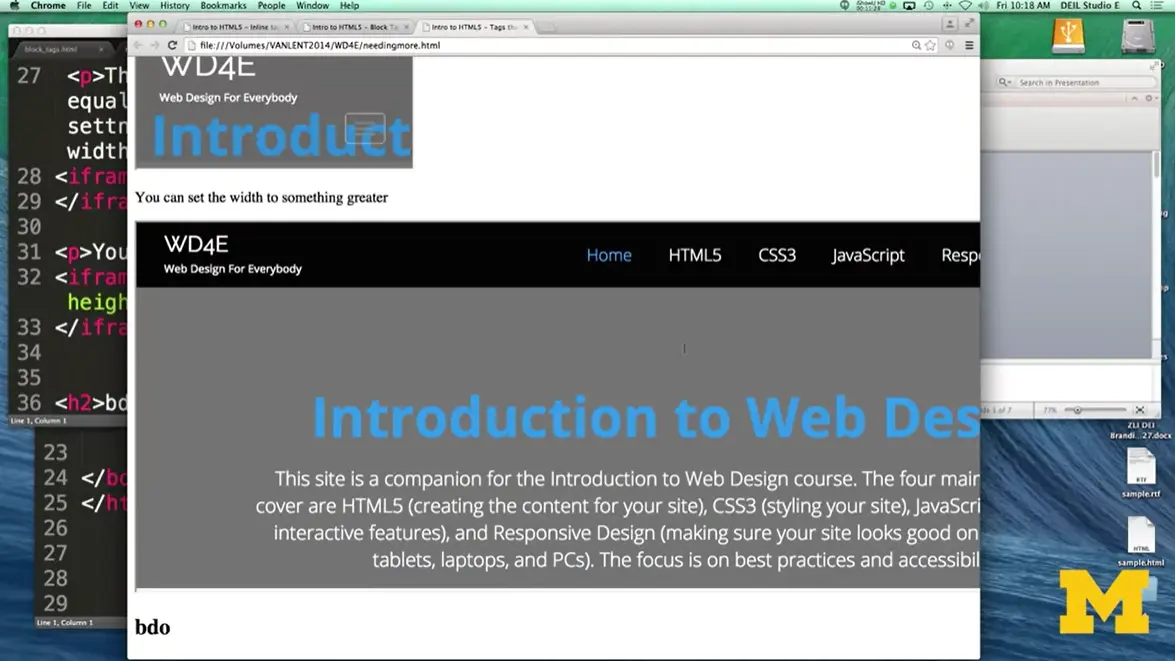

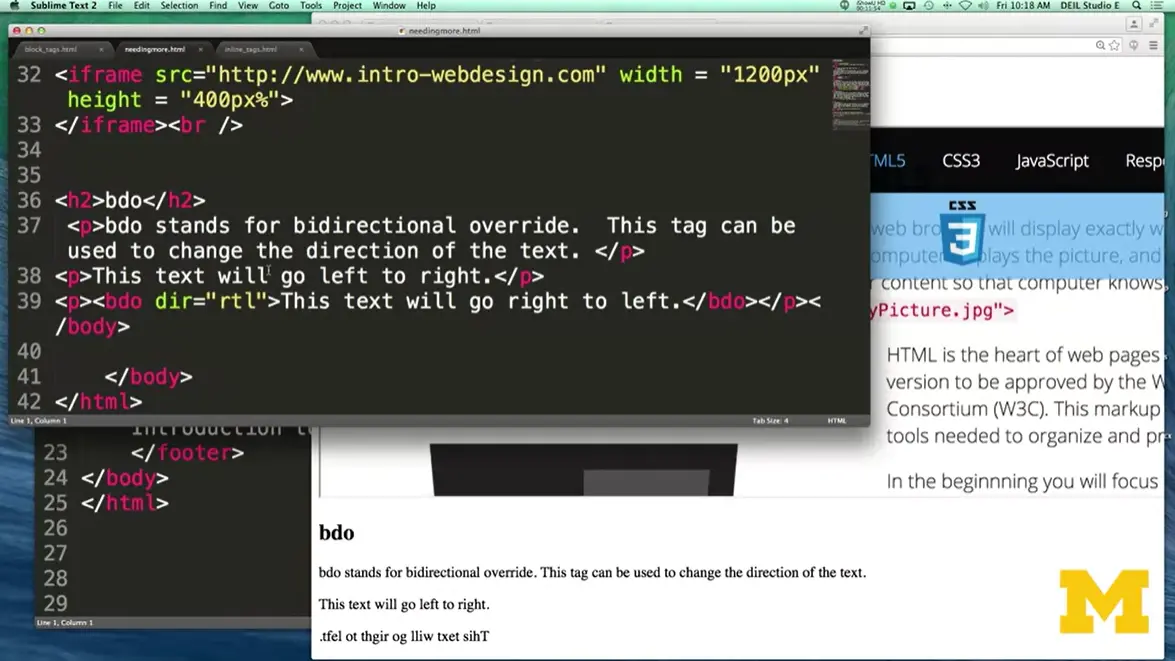

2.09 Useful Tags

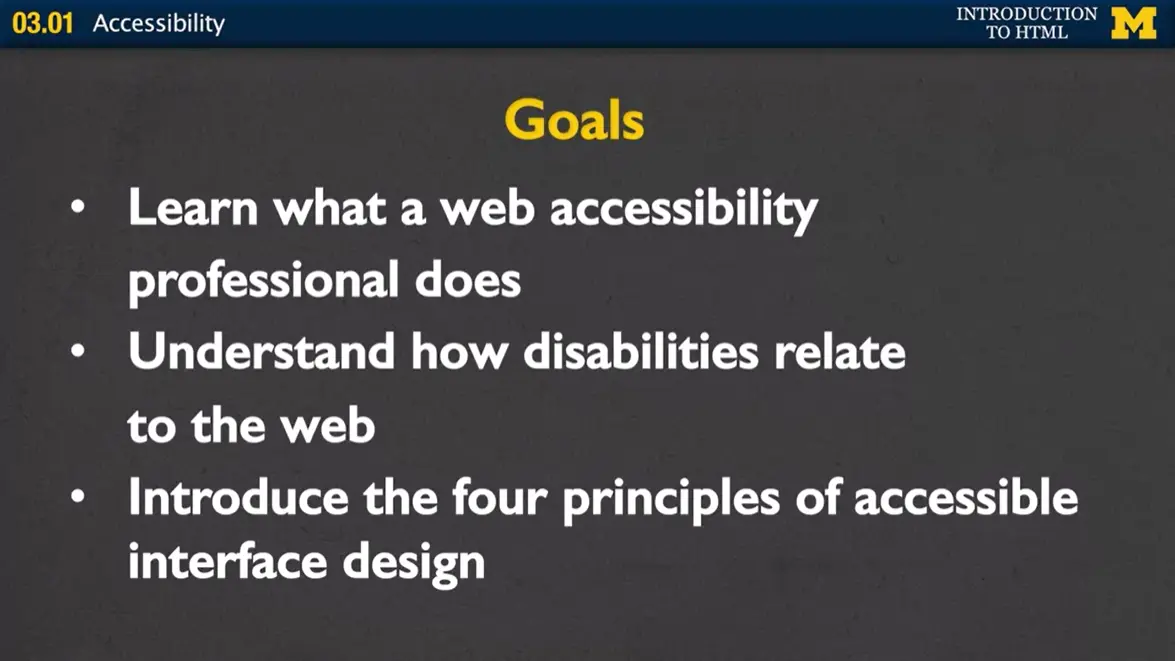

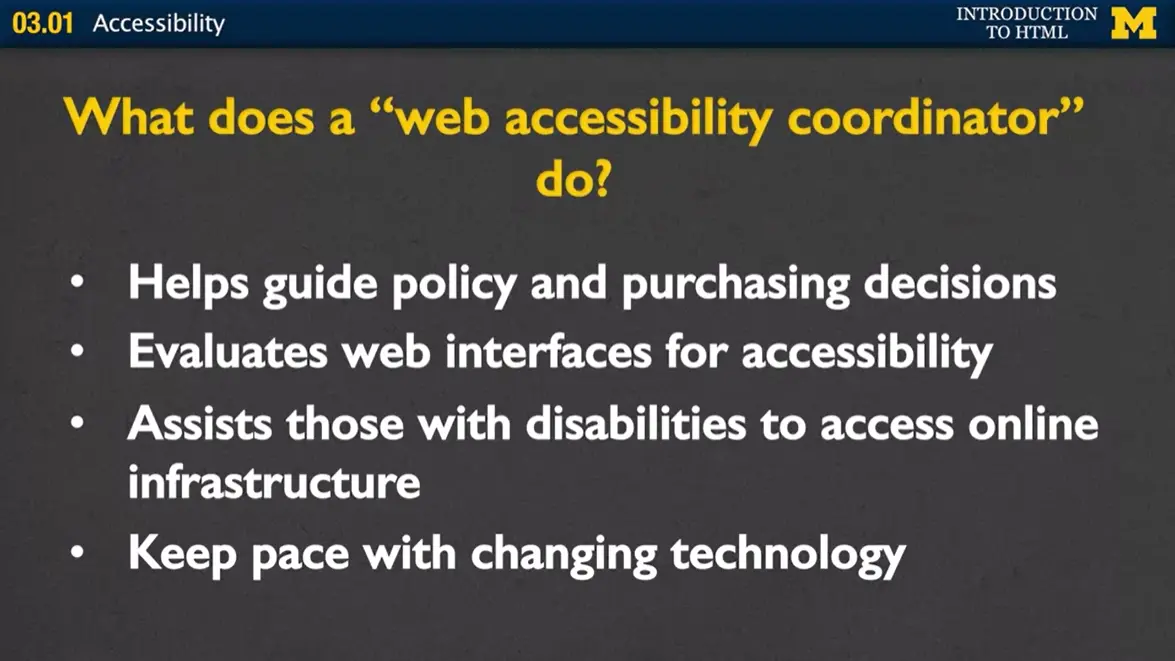

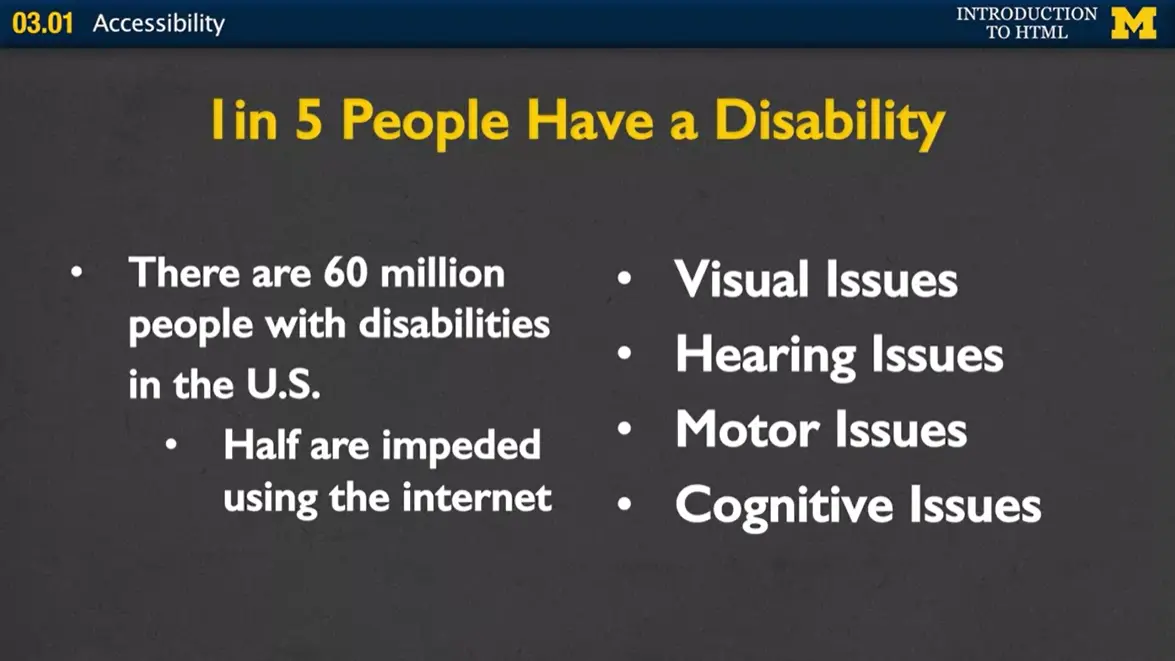

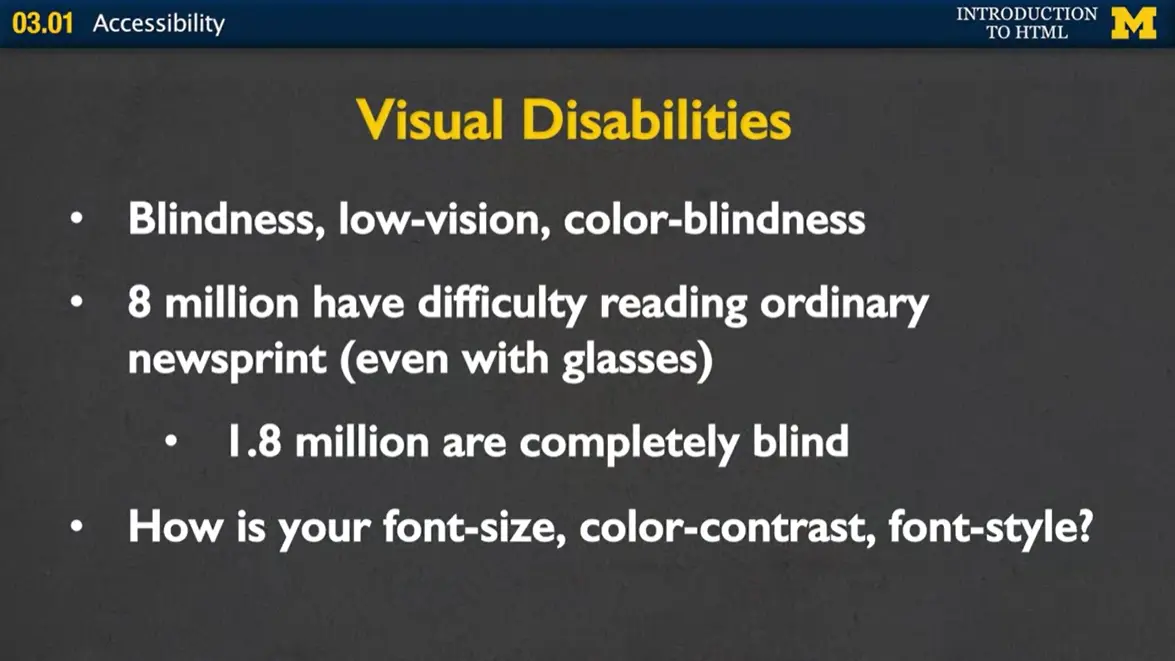

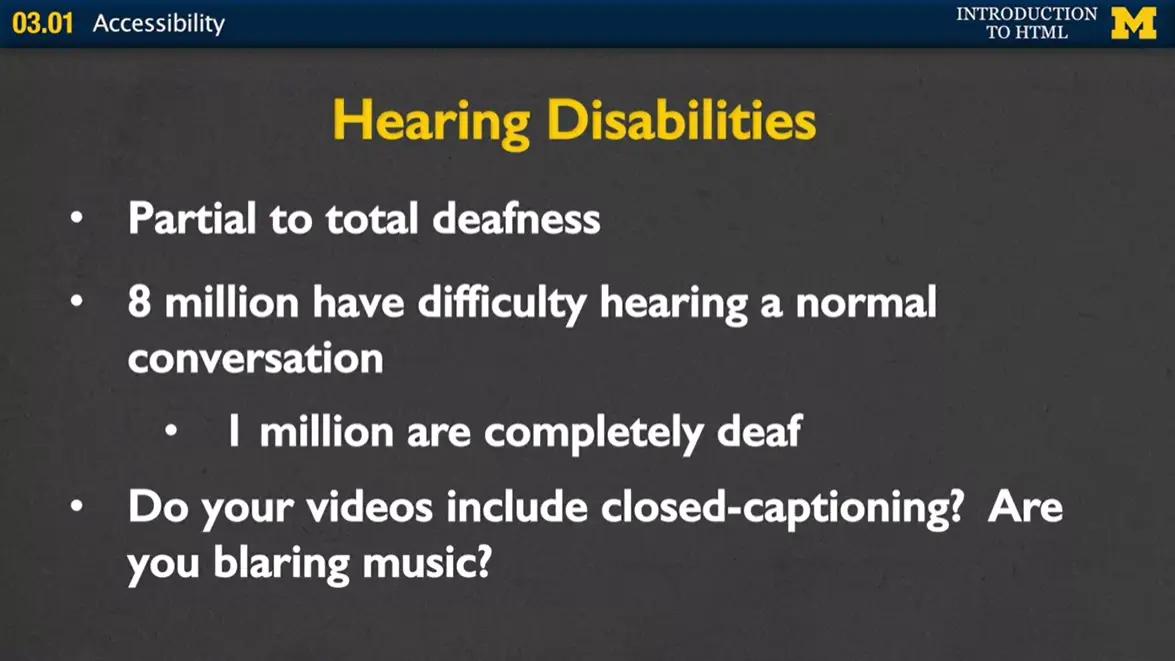

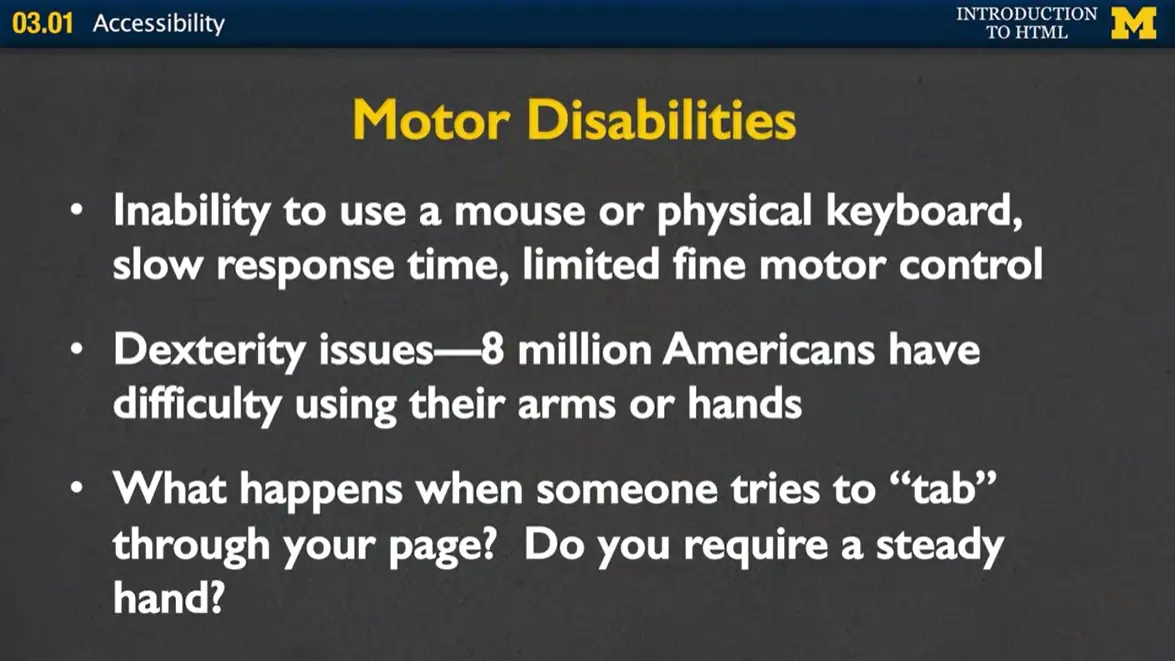

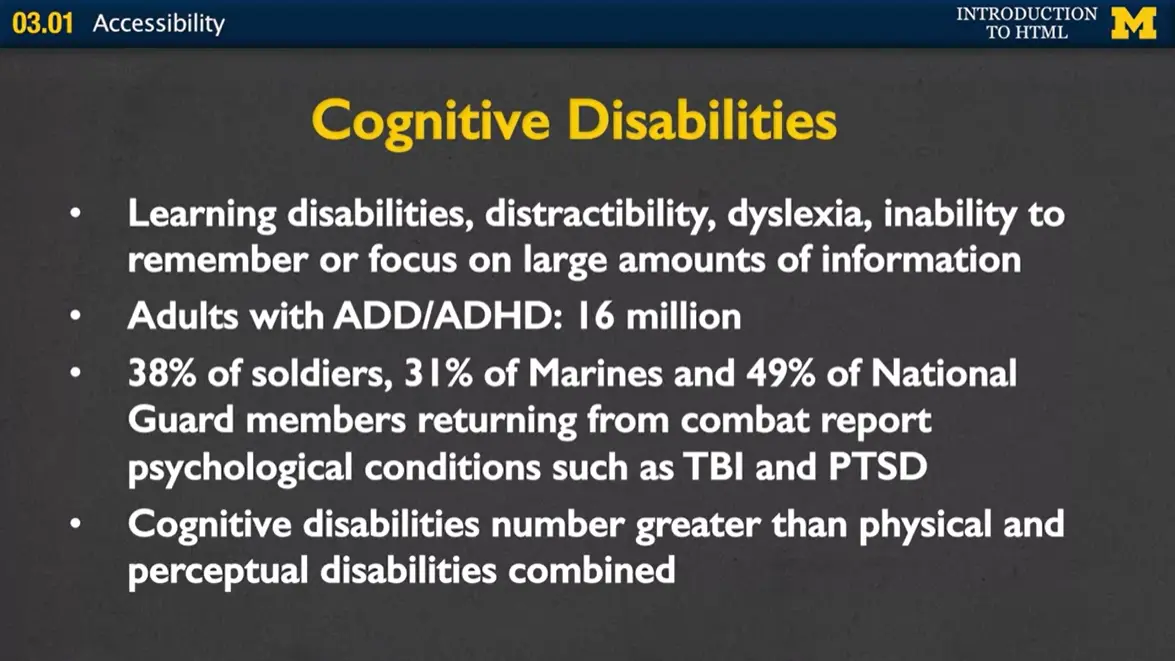

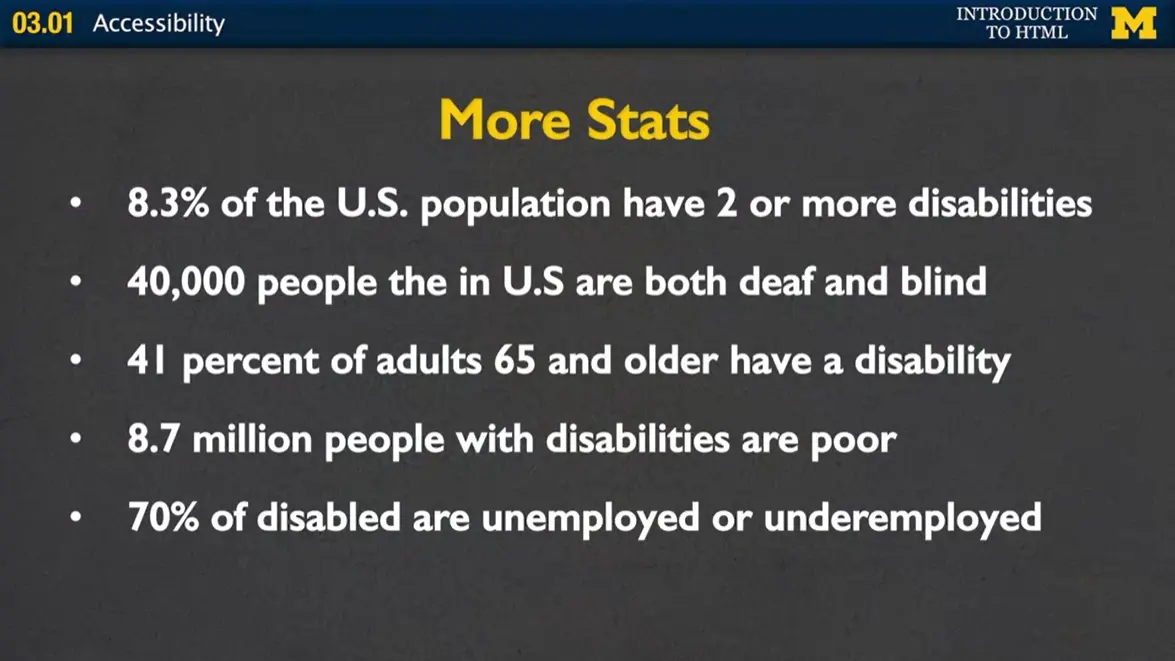

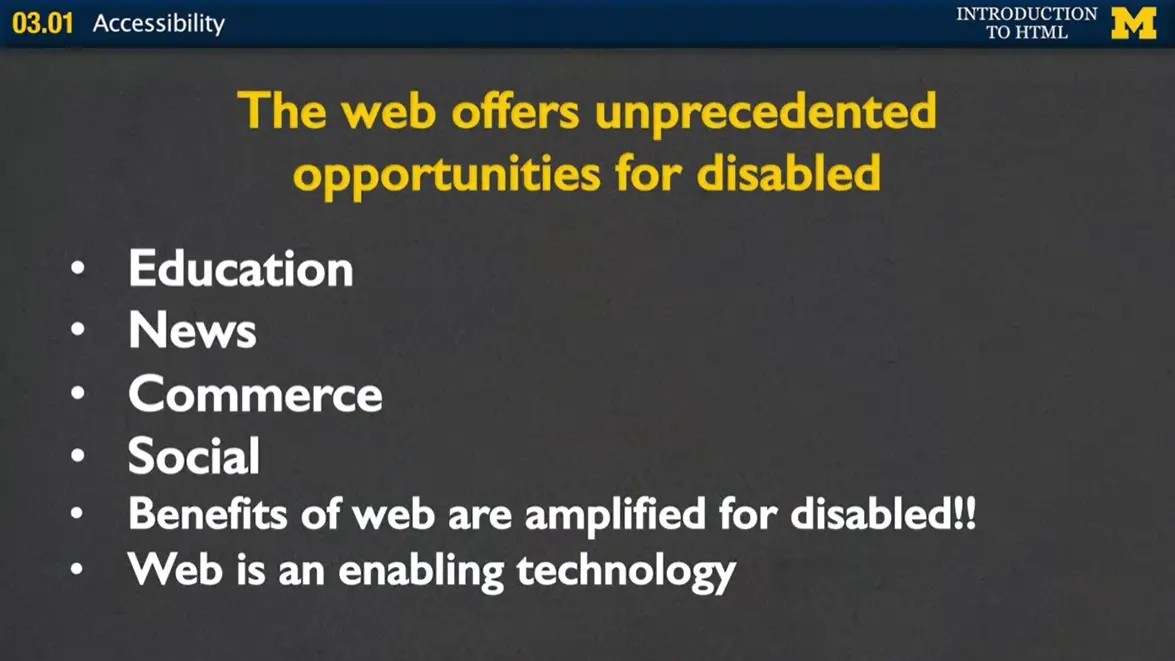

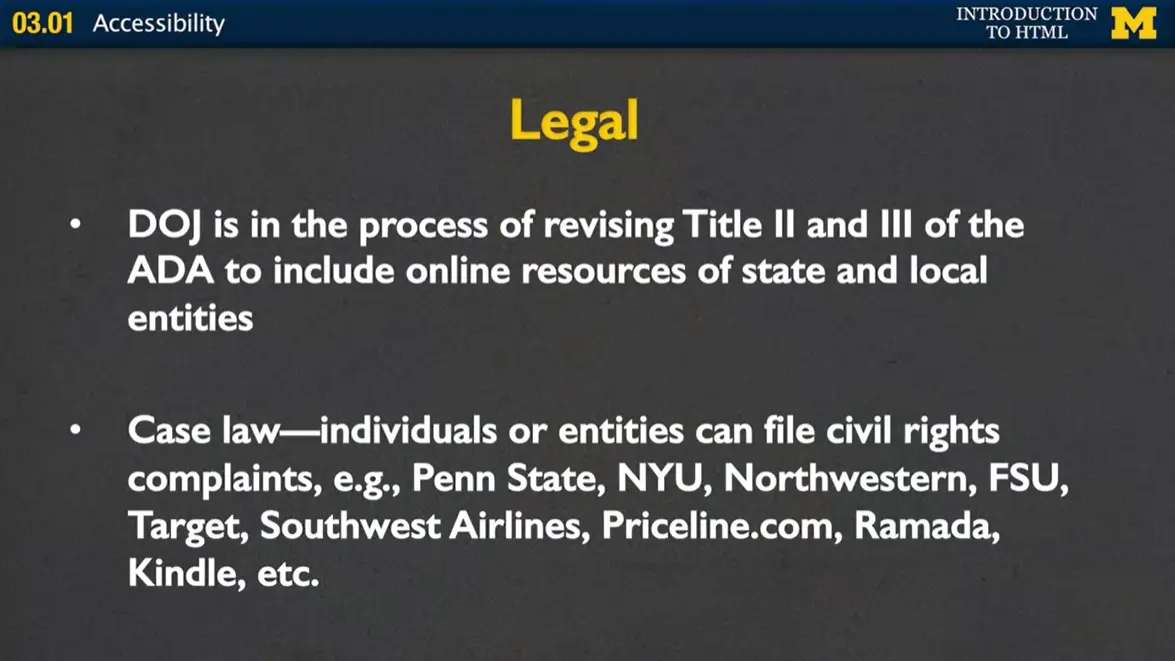

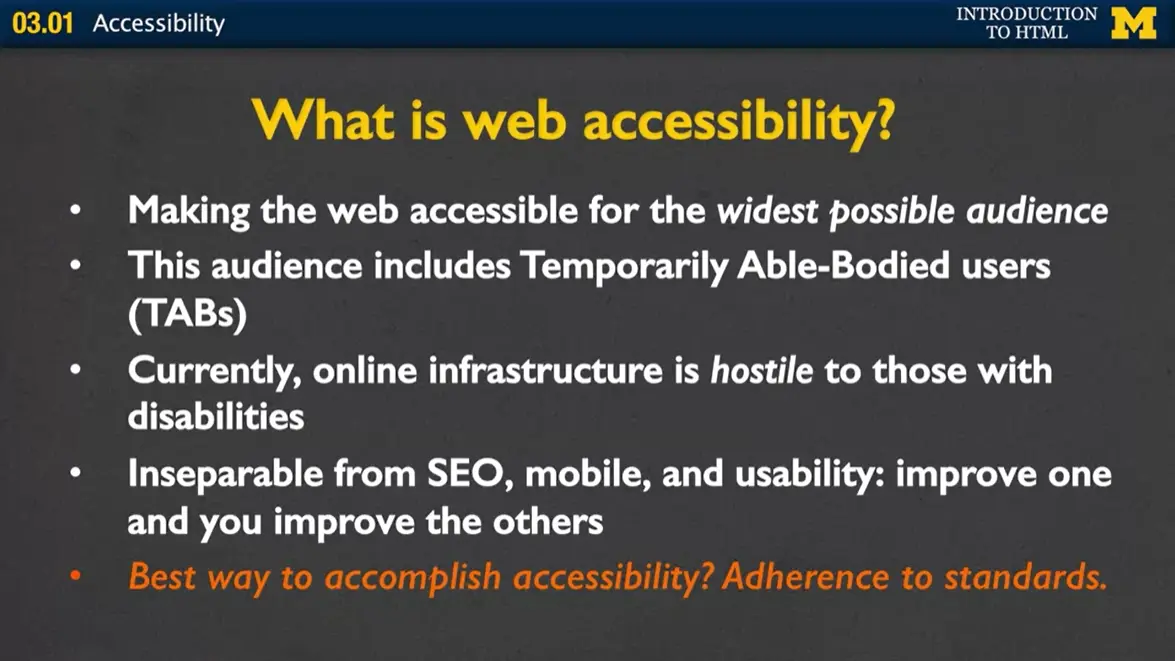

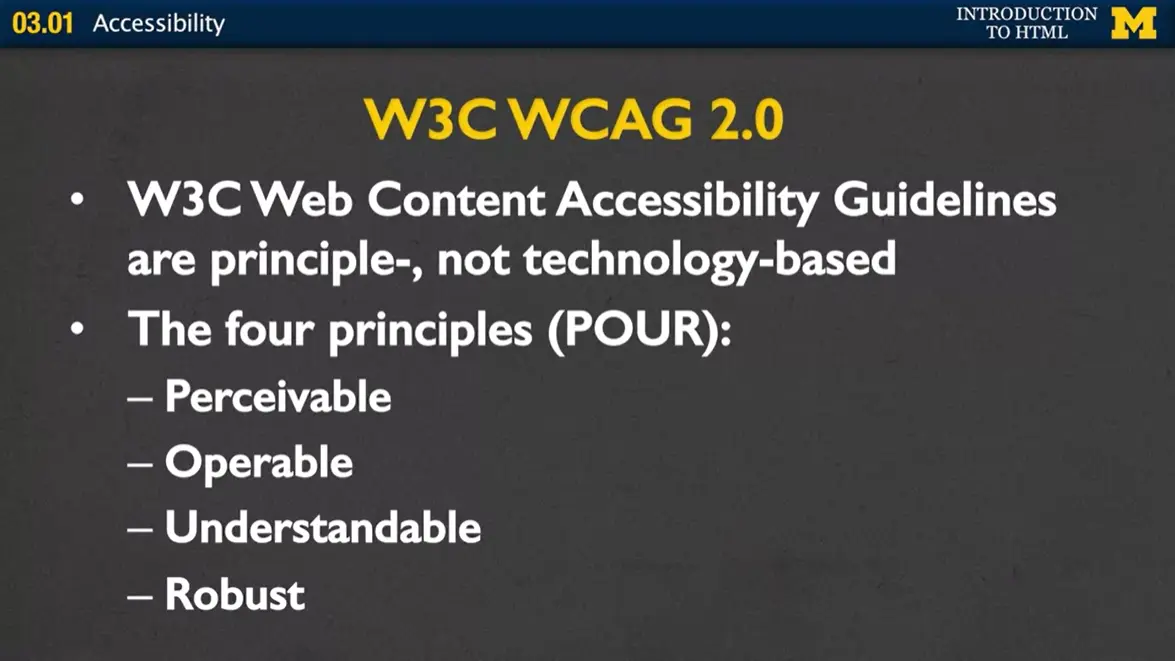

3.01 Accessibility

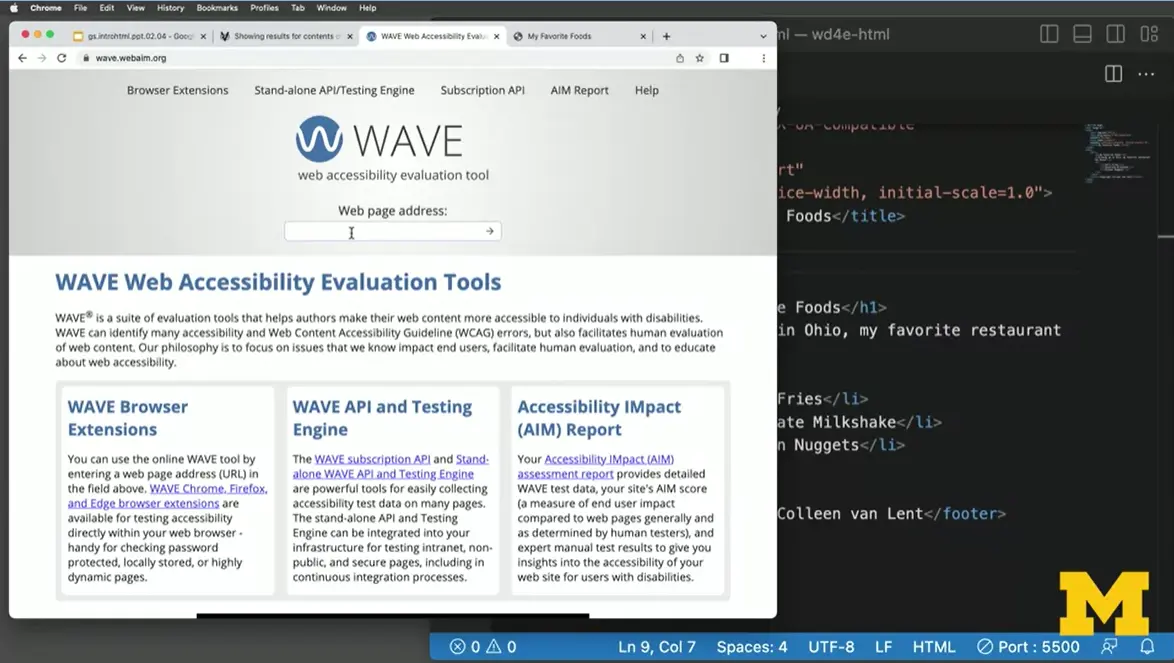

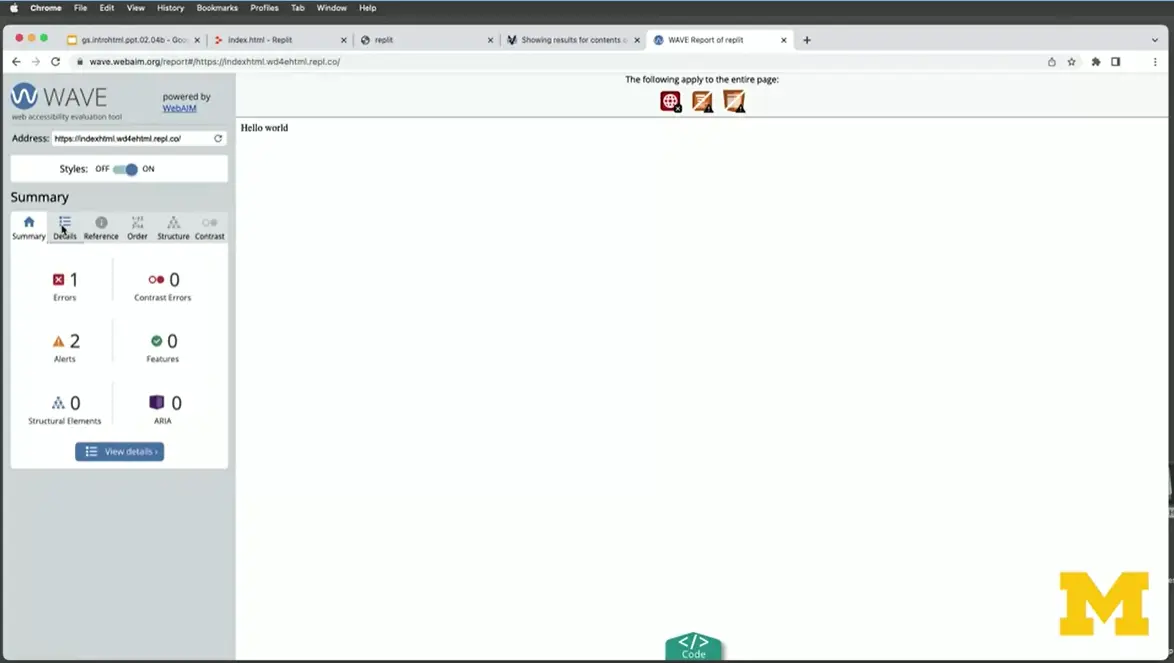

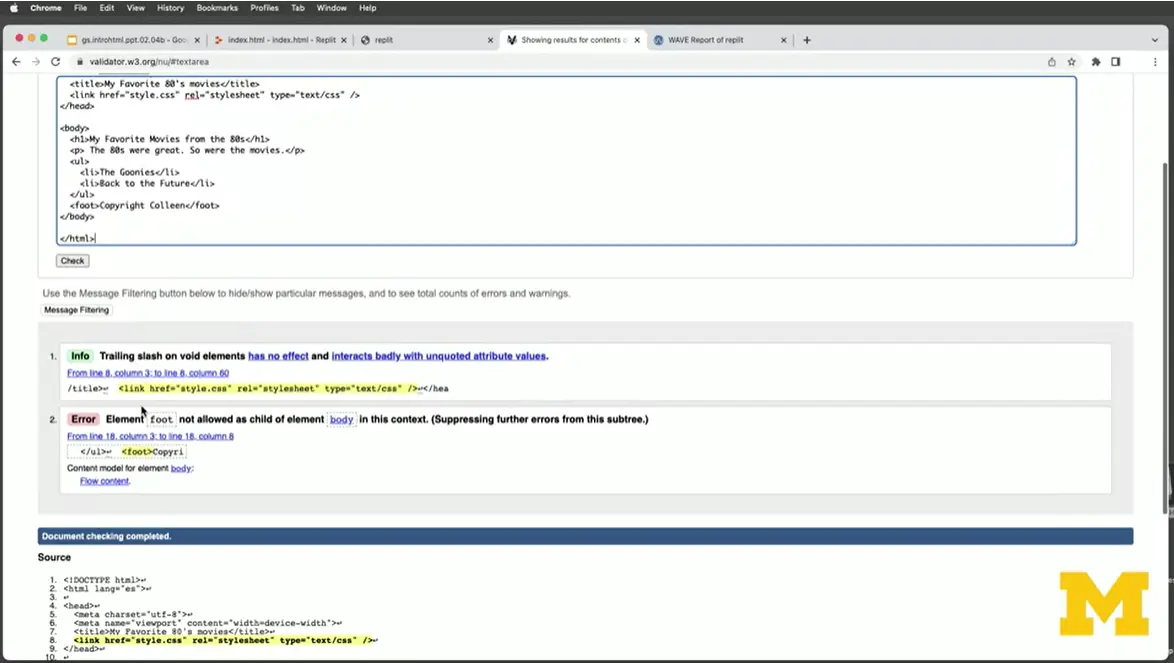

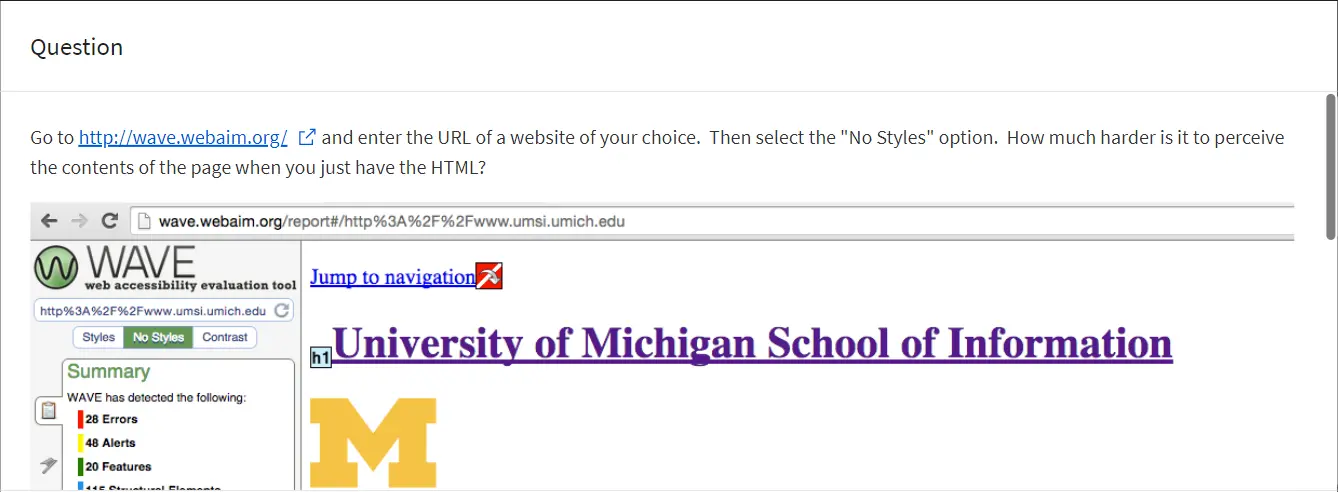

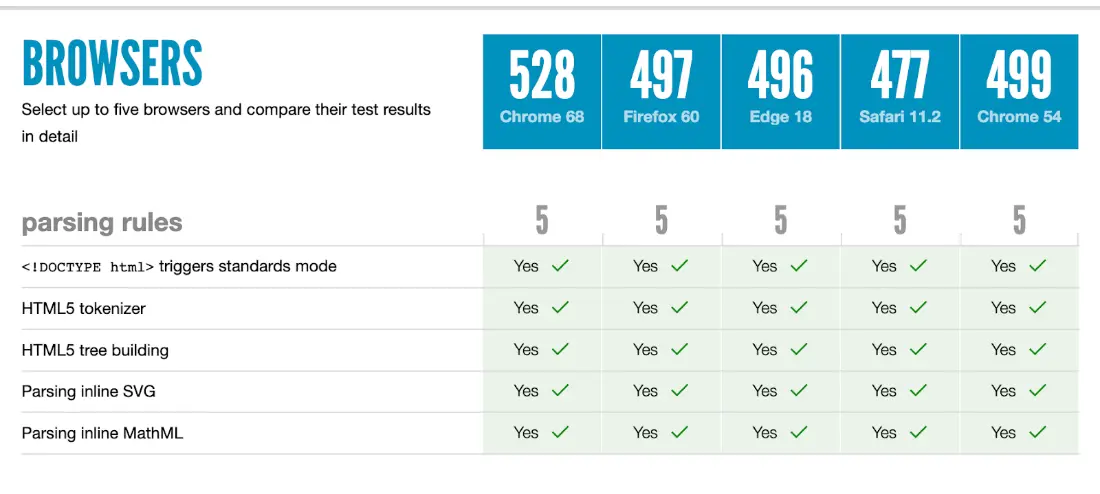

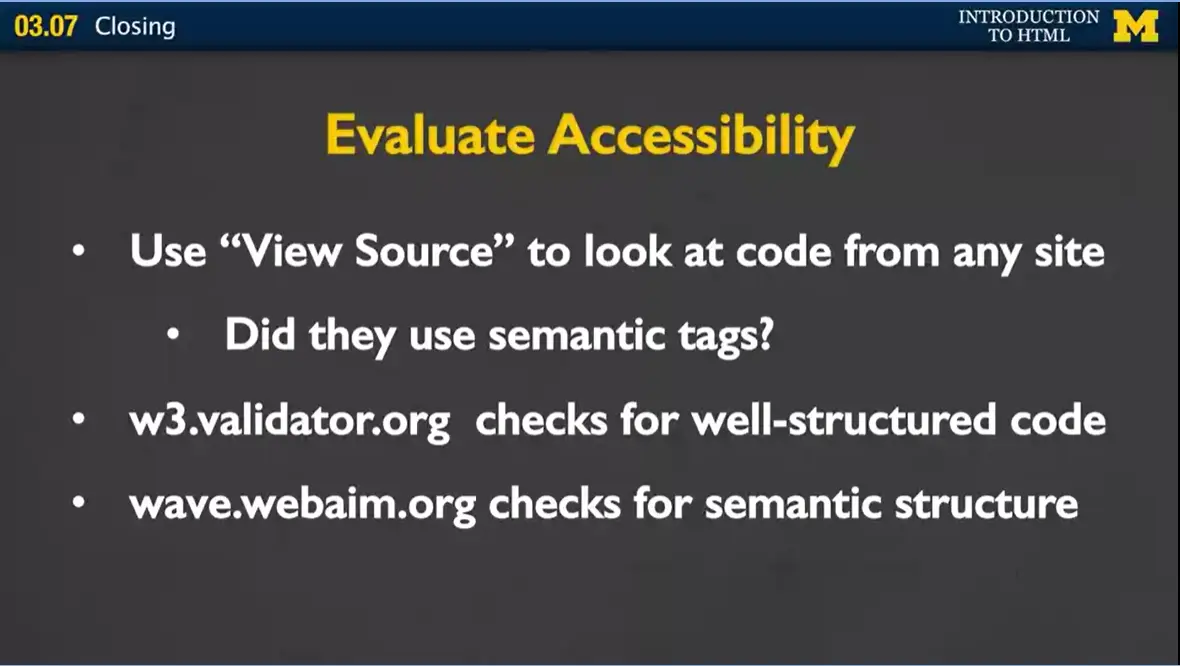

3.02 Validating Your Site

3.03 Hosting Your Site

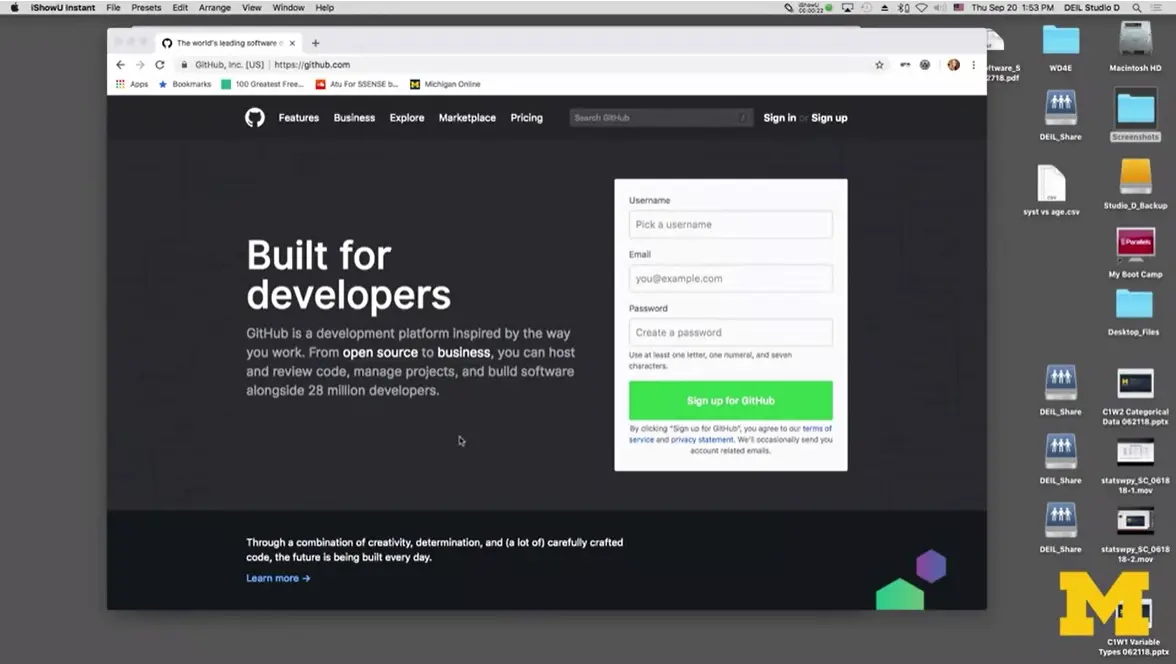

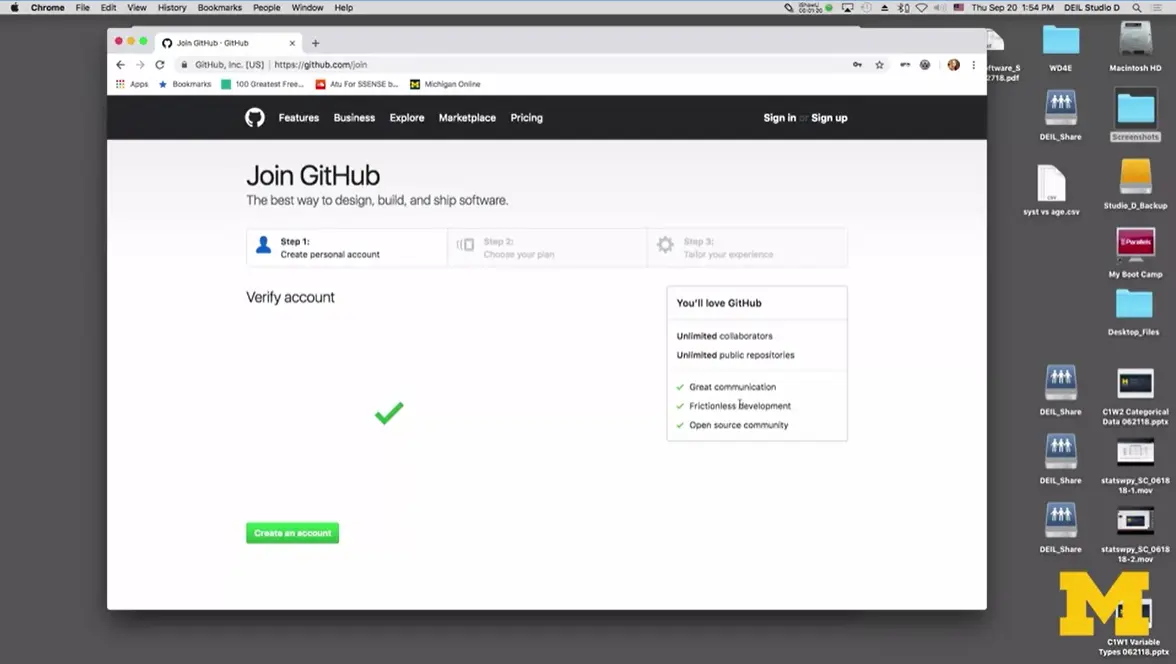

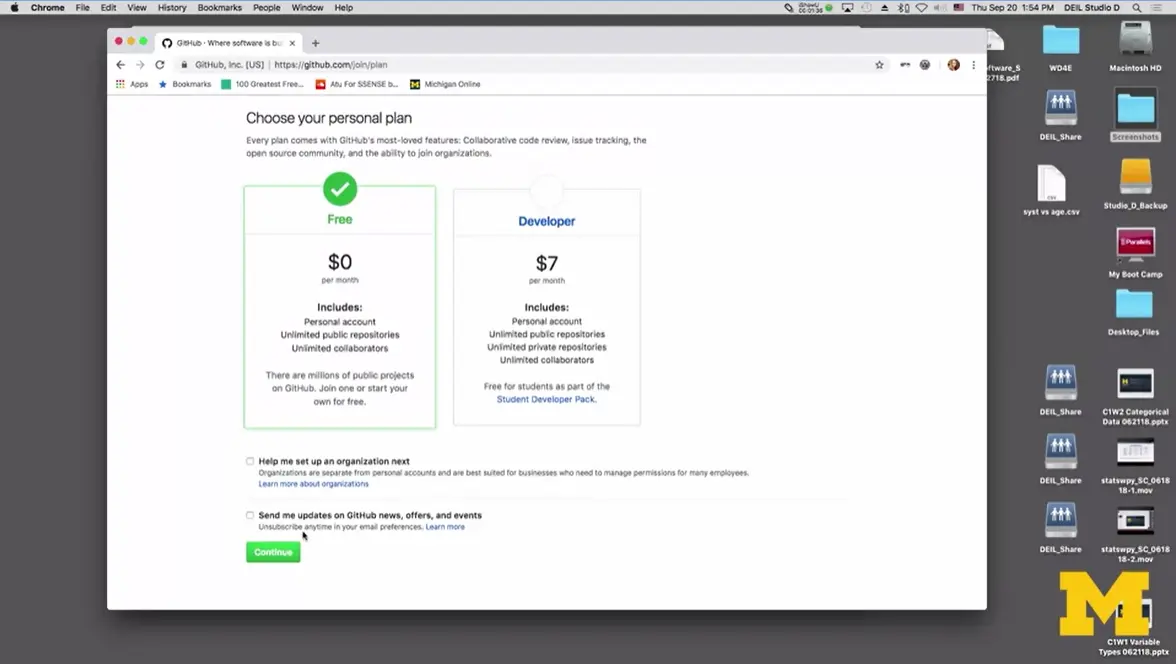

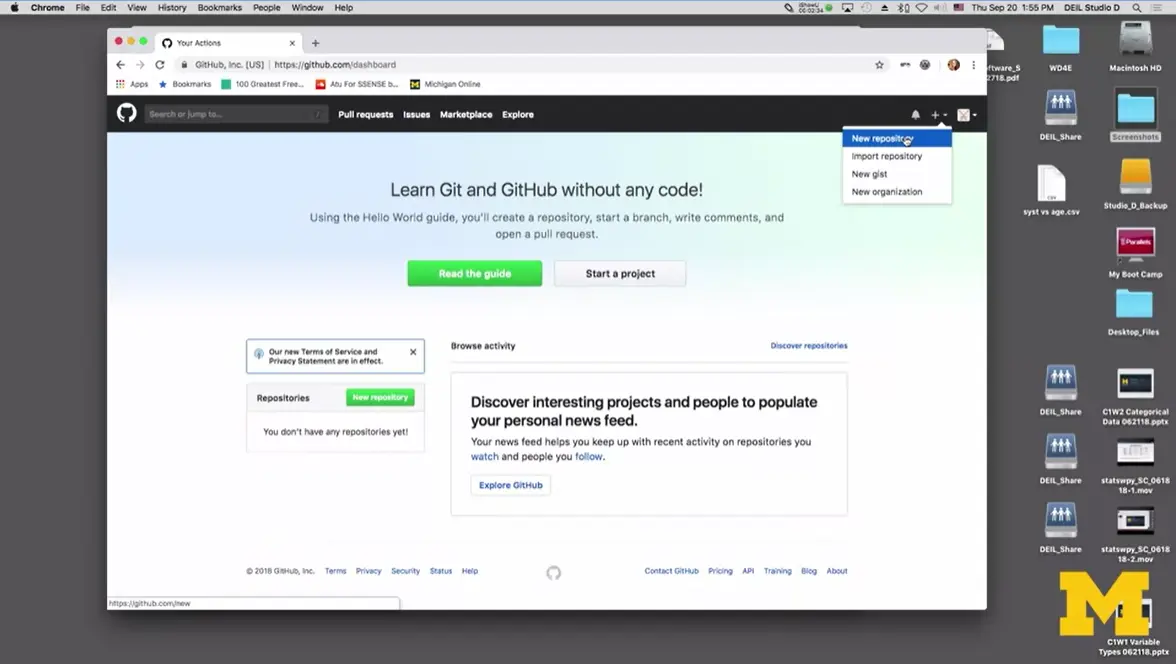

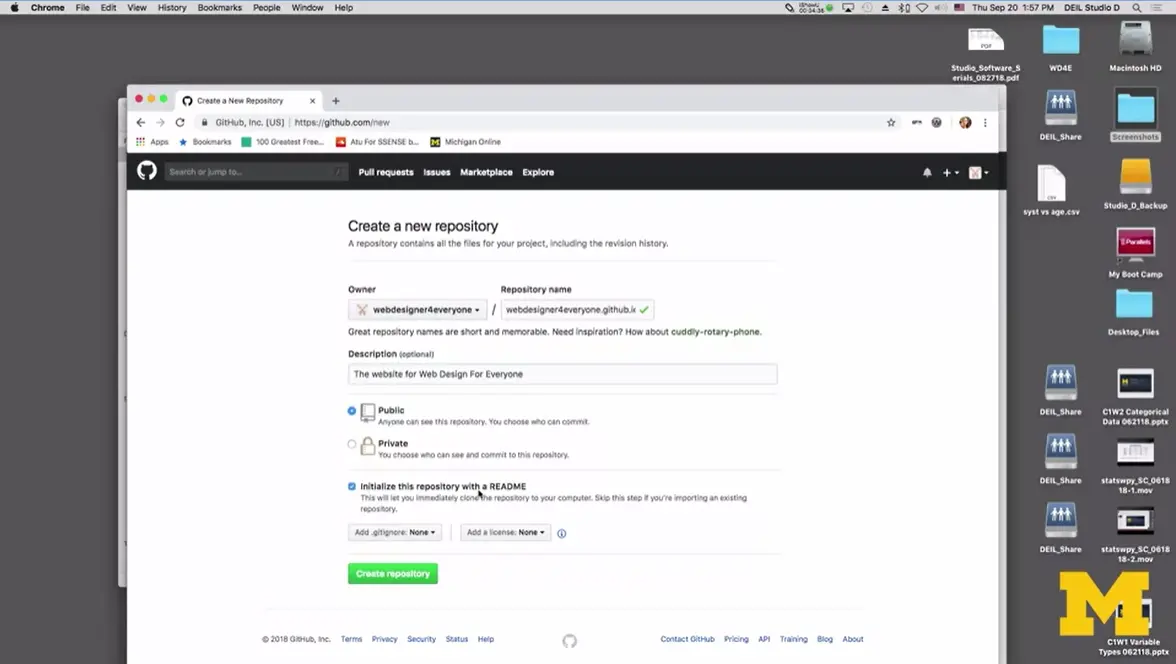

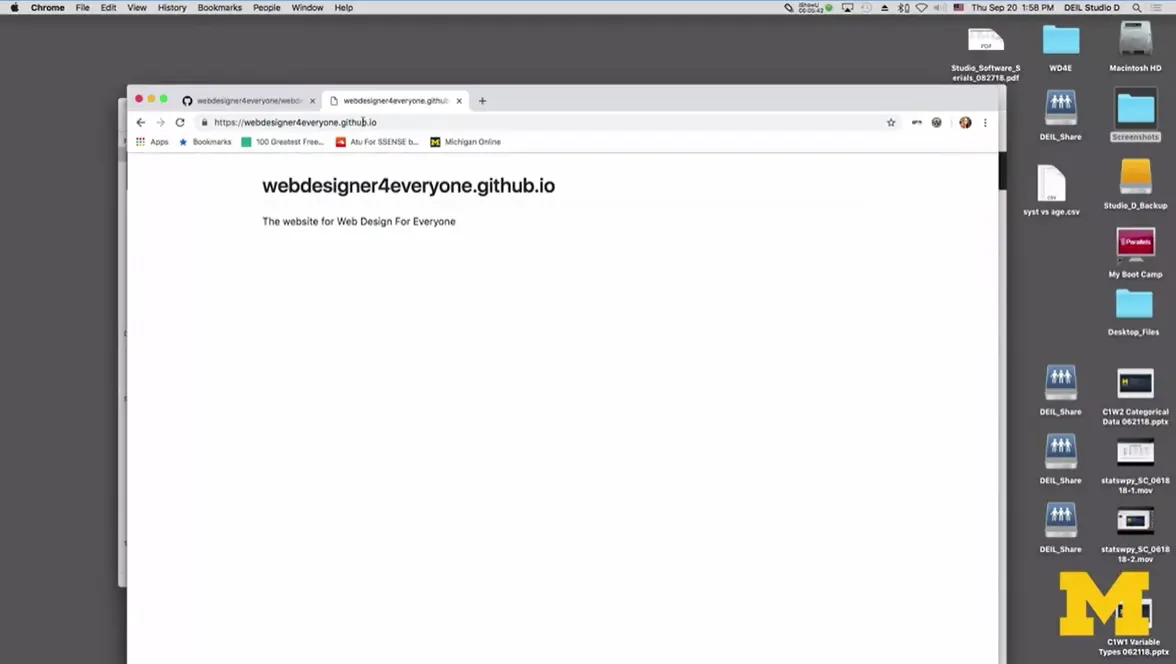

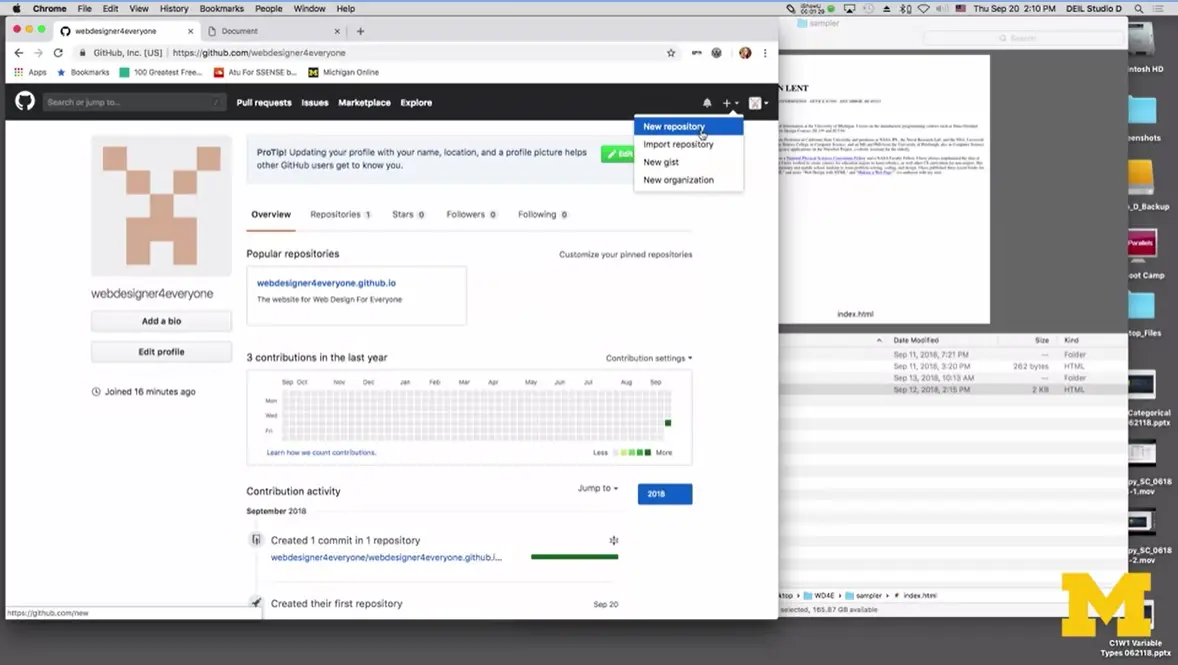

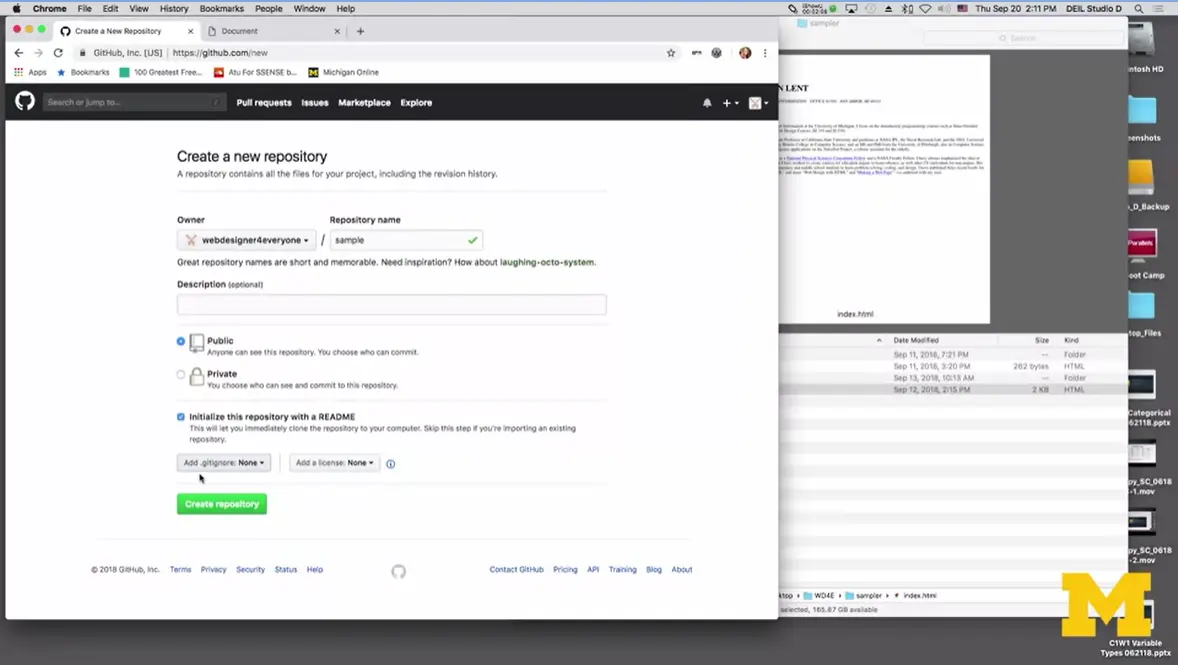

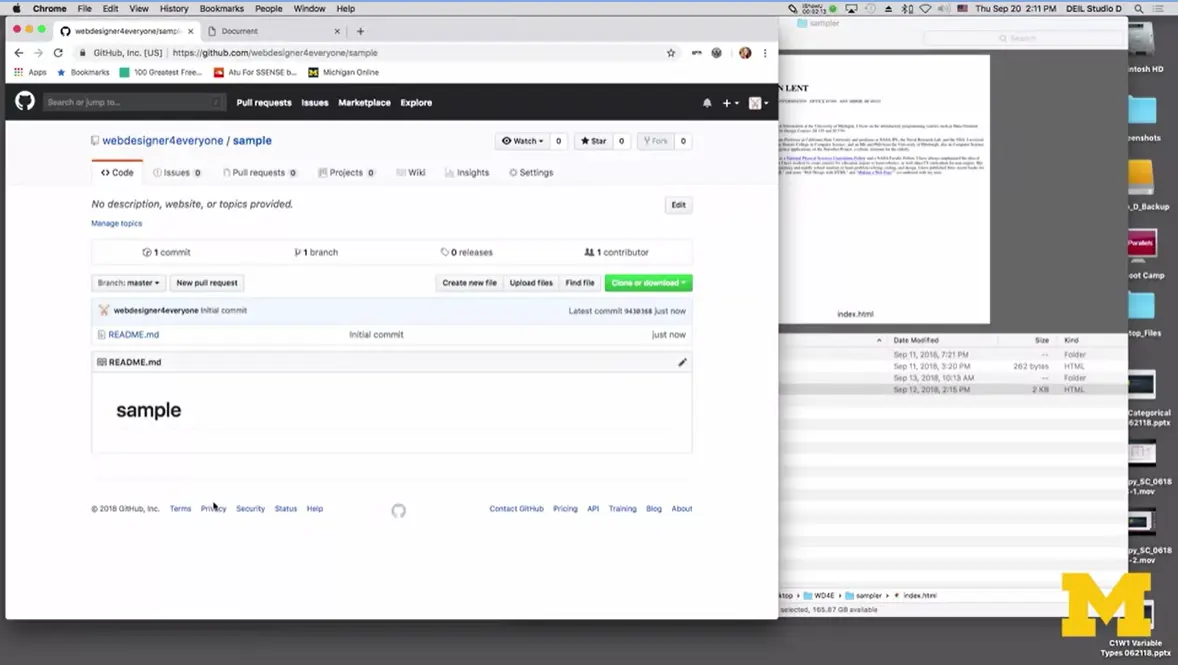

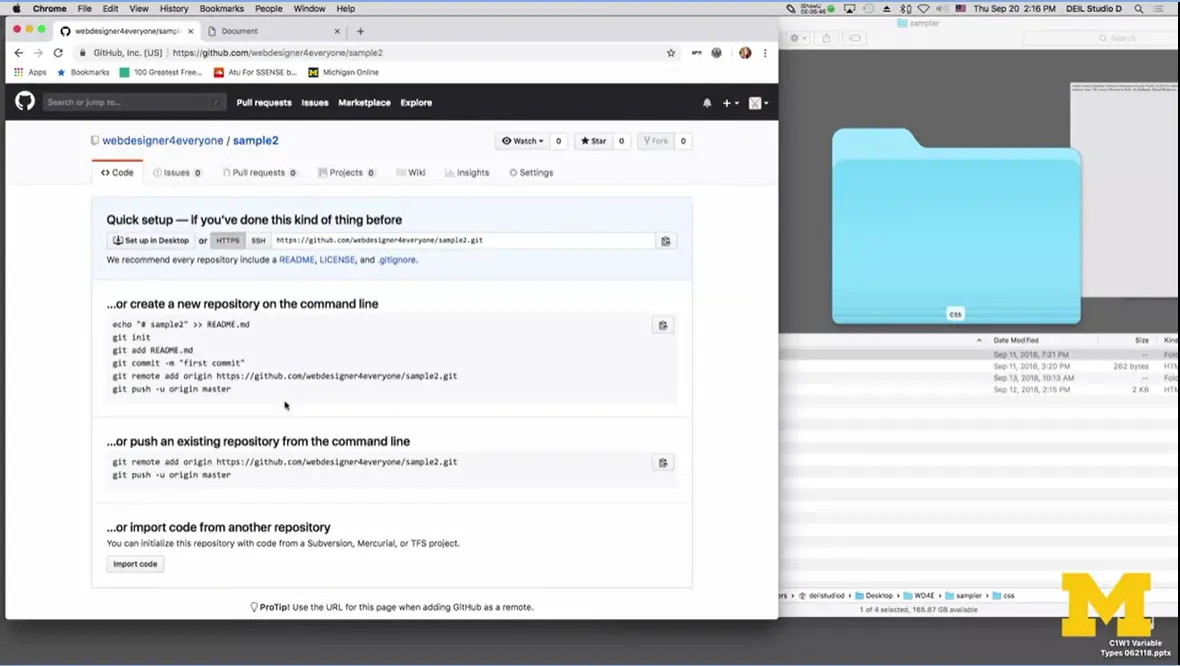

3.04a Creating a GitHub Pages Account

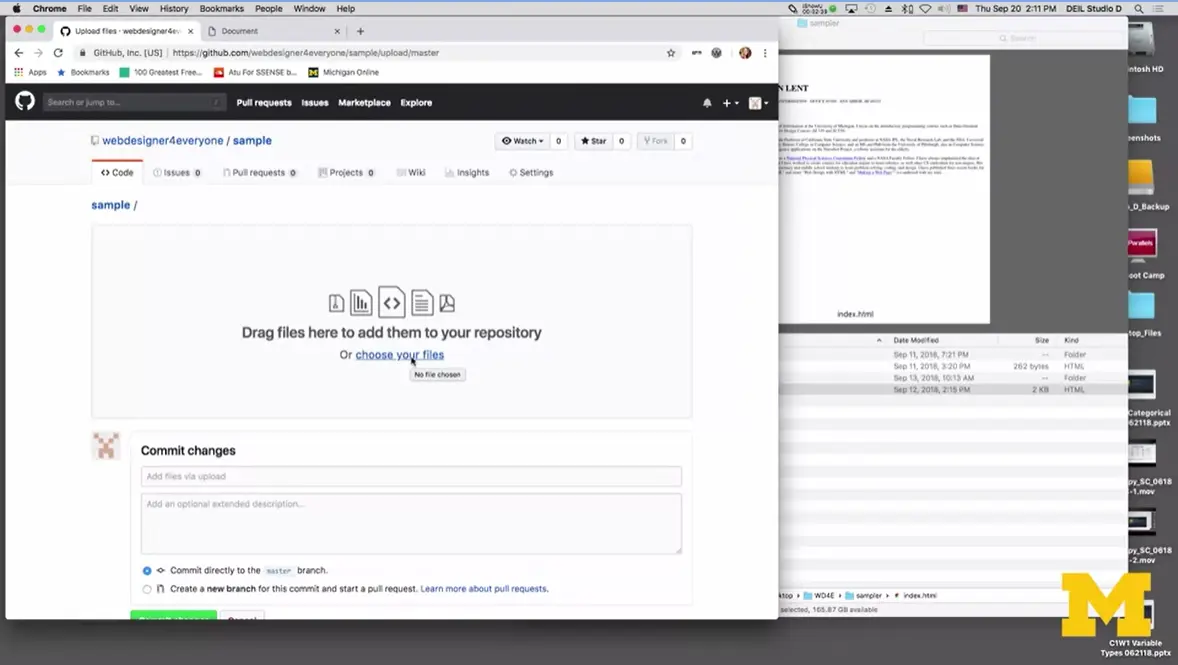

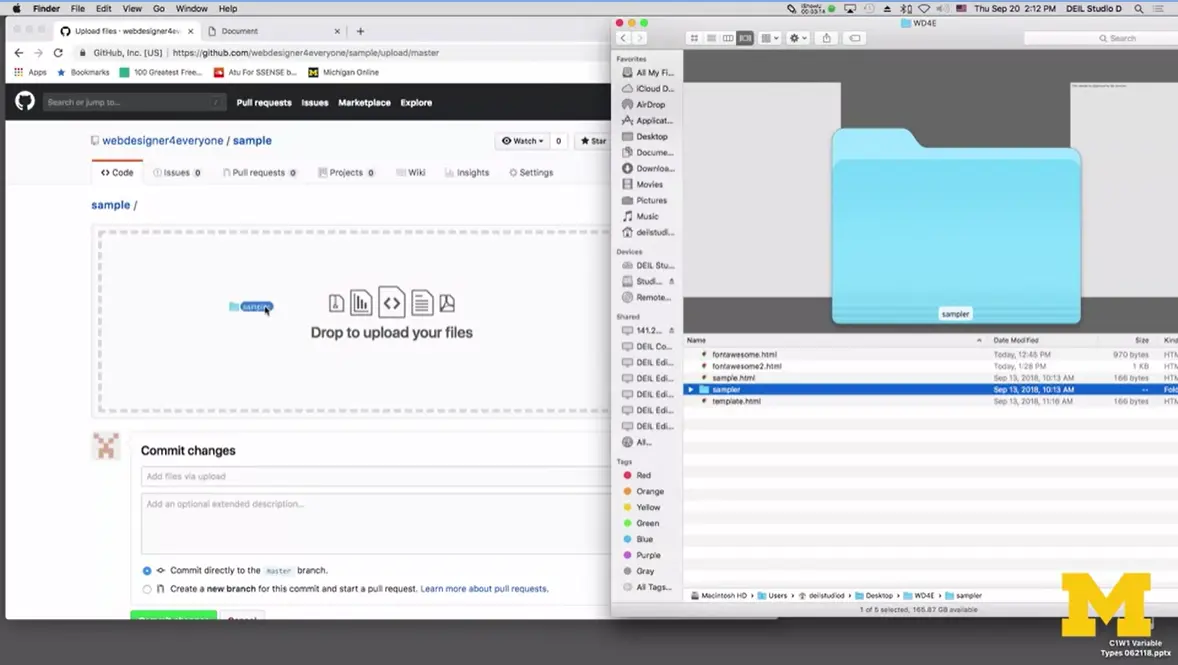

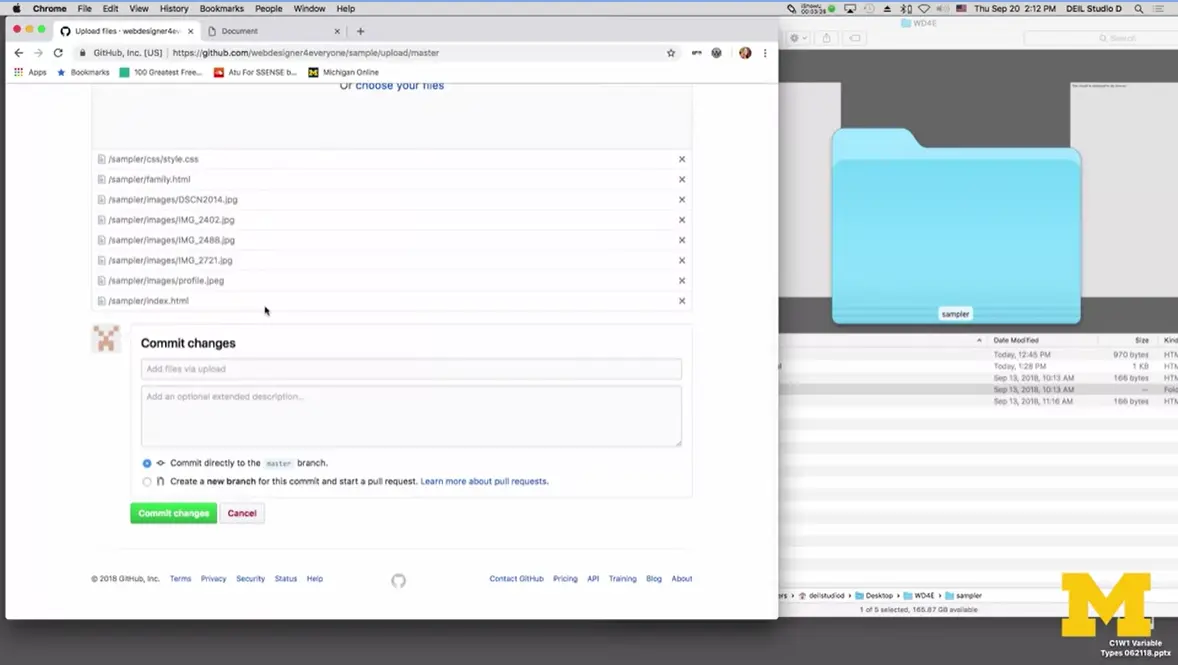

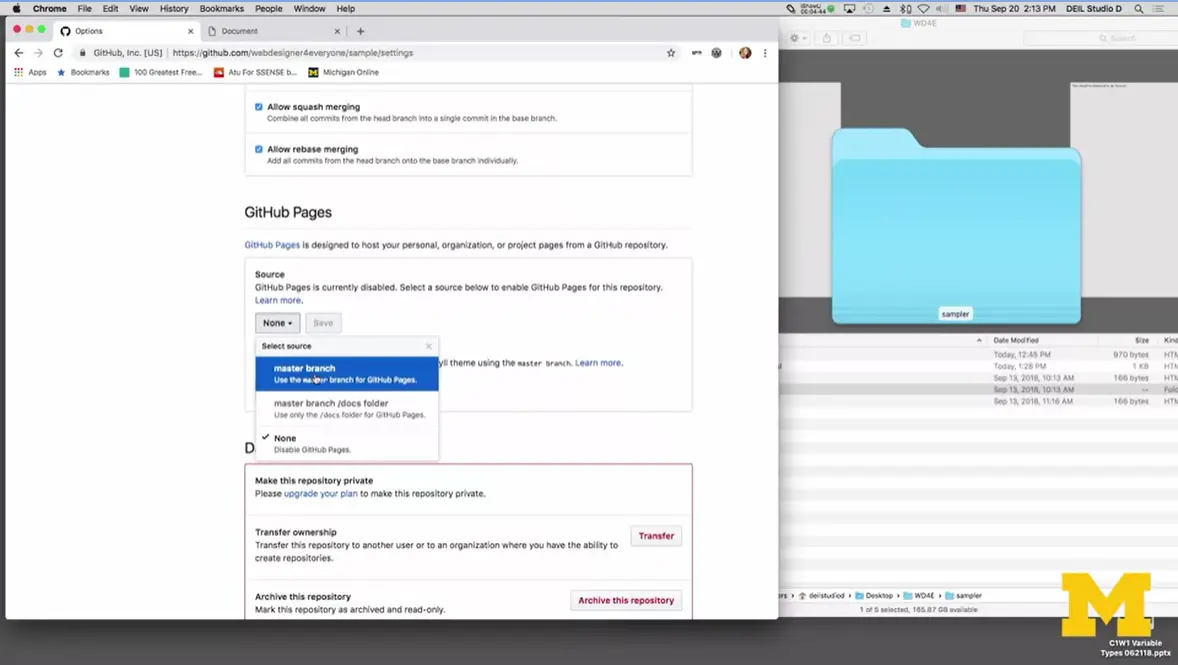

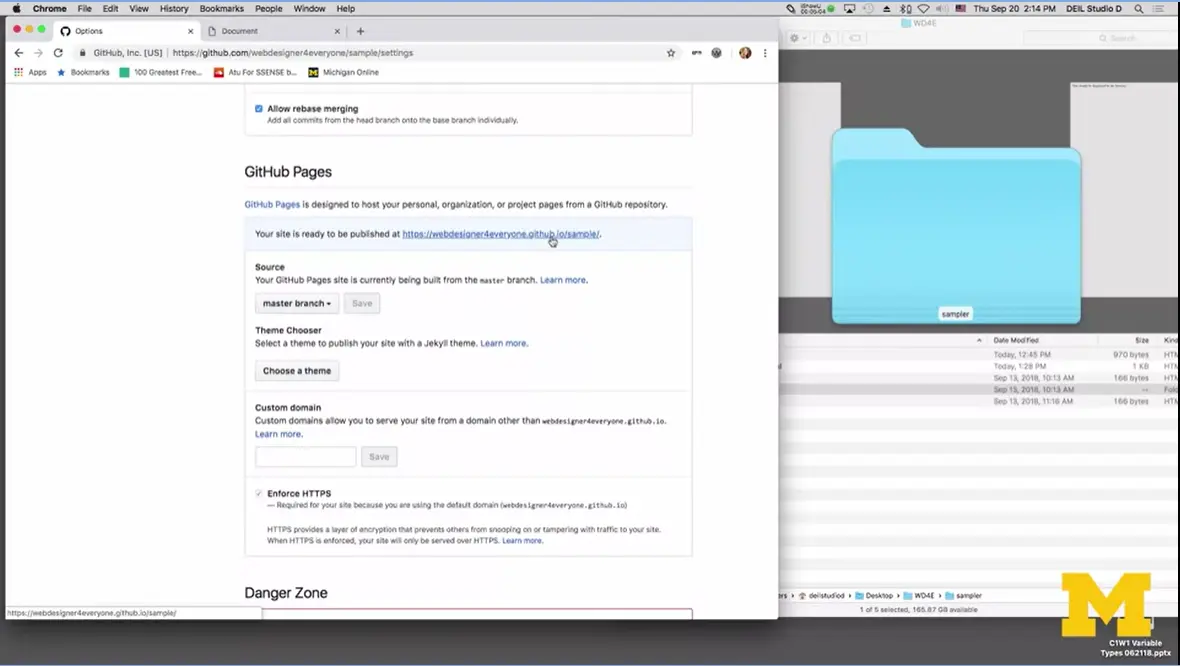

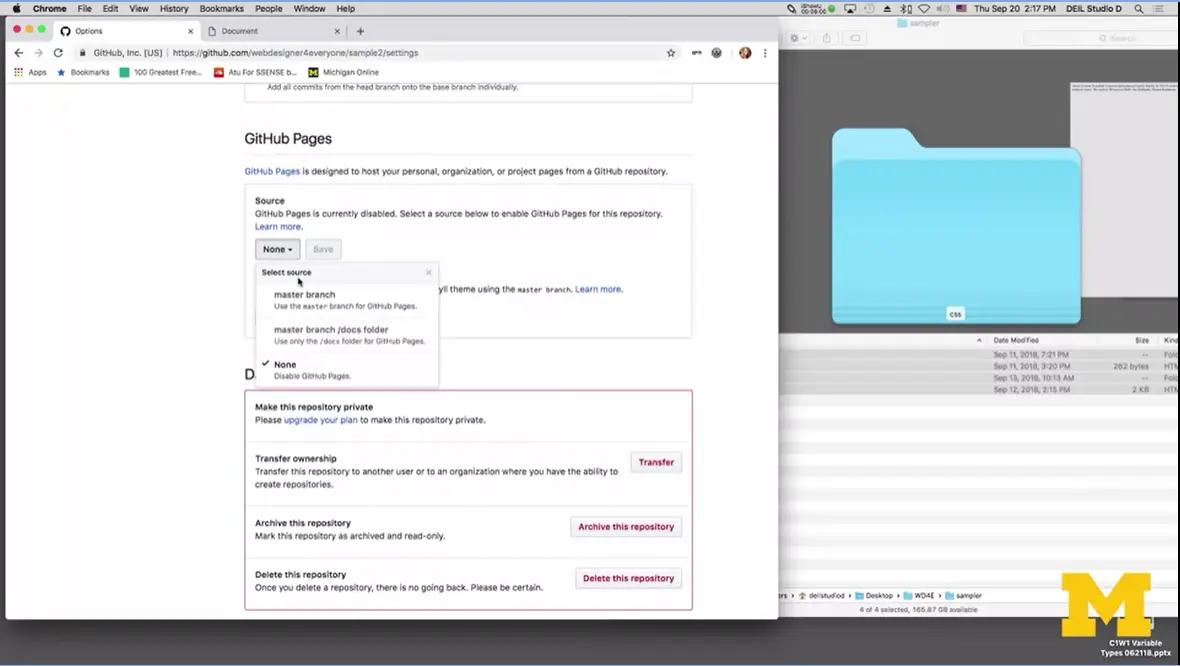

3.04b Uploading to GitHub Pages Account

3.05 Sharing Your Page from Replit

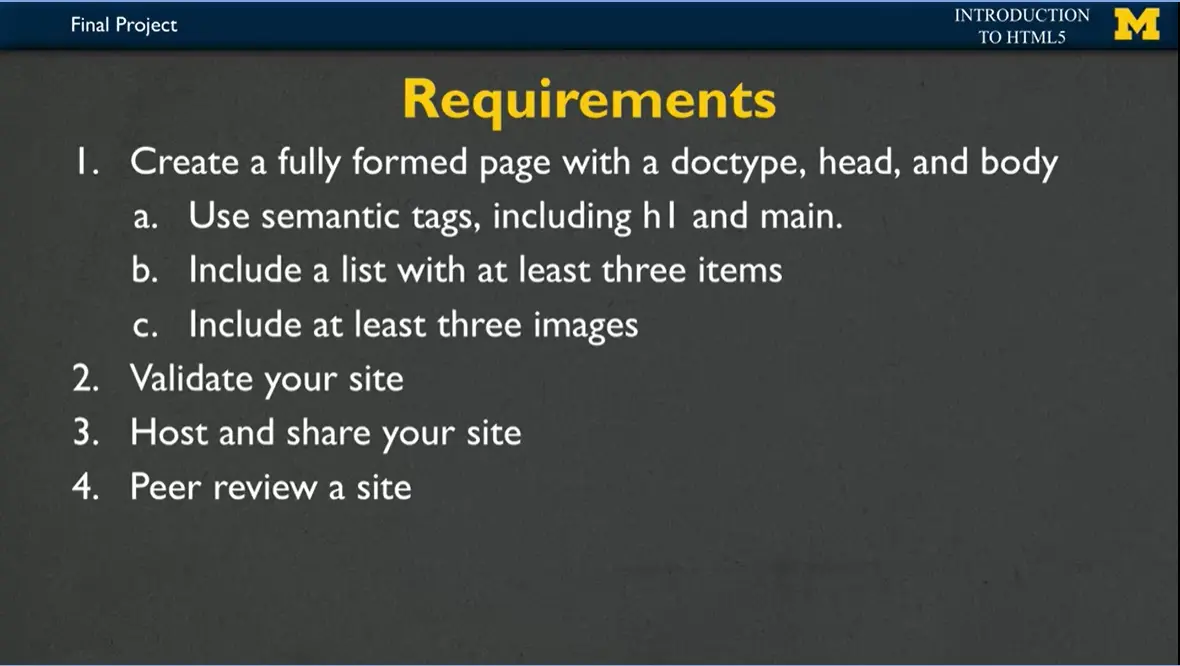

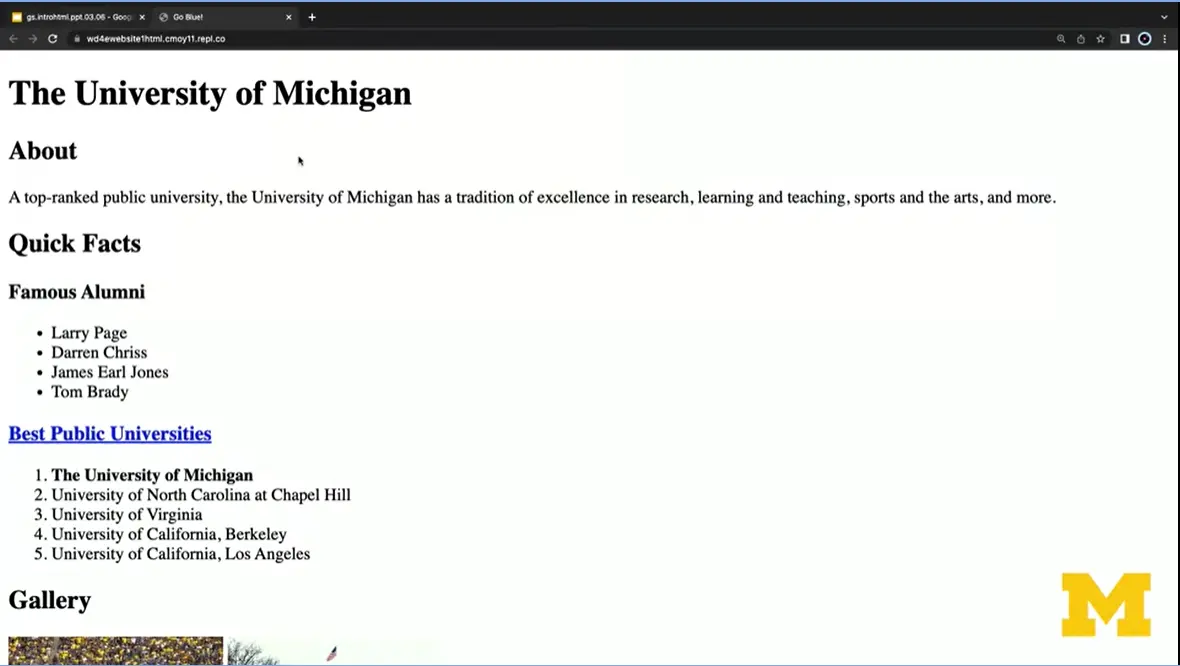

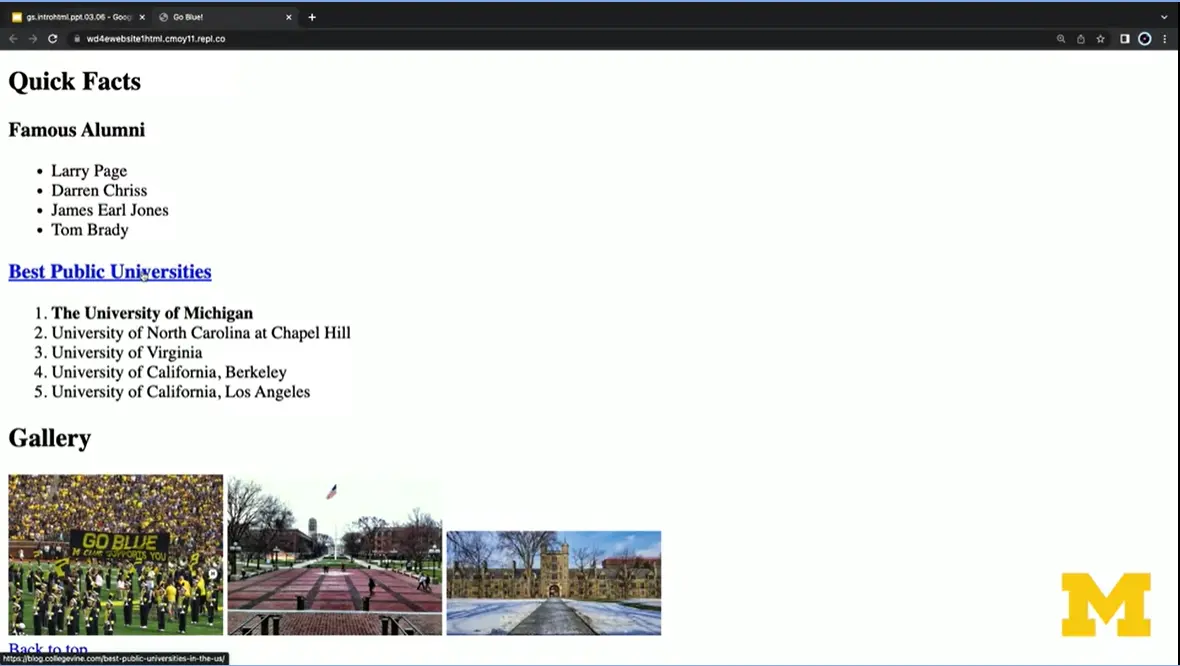

3.06 Final Project

3.07 Closing

This week we will uncover the "mystery" behind the Internet. What happens when you type a URL into your browser so that a webpage magically appears? What is HTML5 and what happened to HTML 1 - 4? We will also cover some practical concepts that you need to master before you begin coding your own pages.

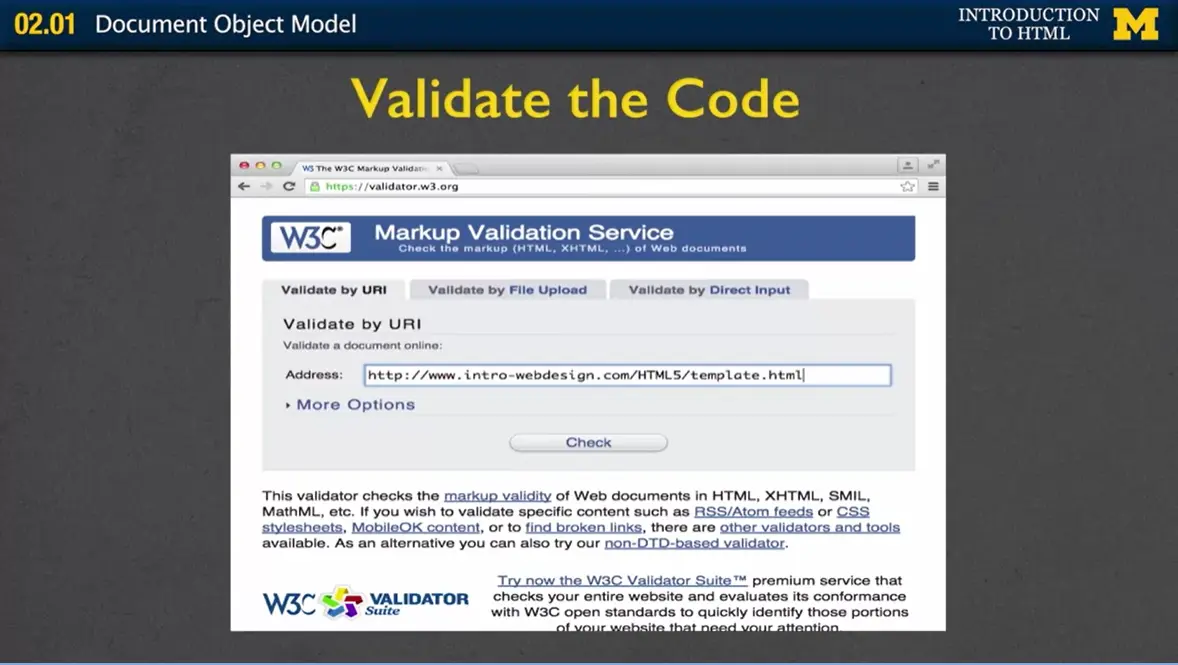

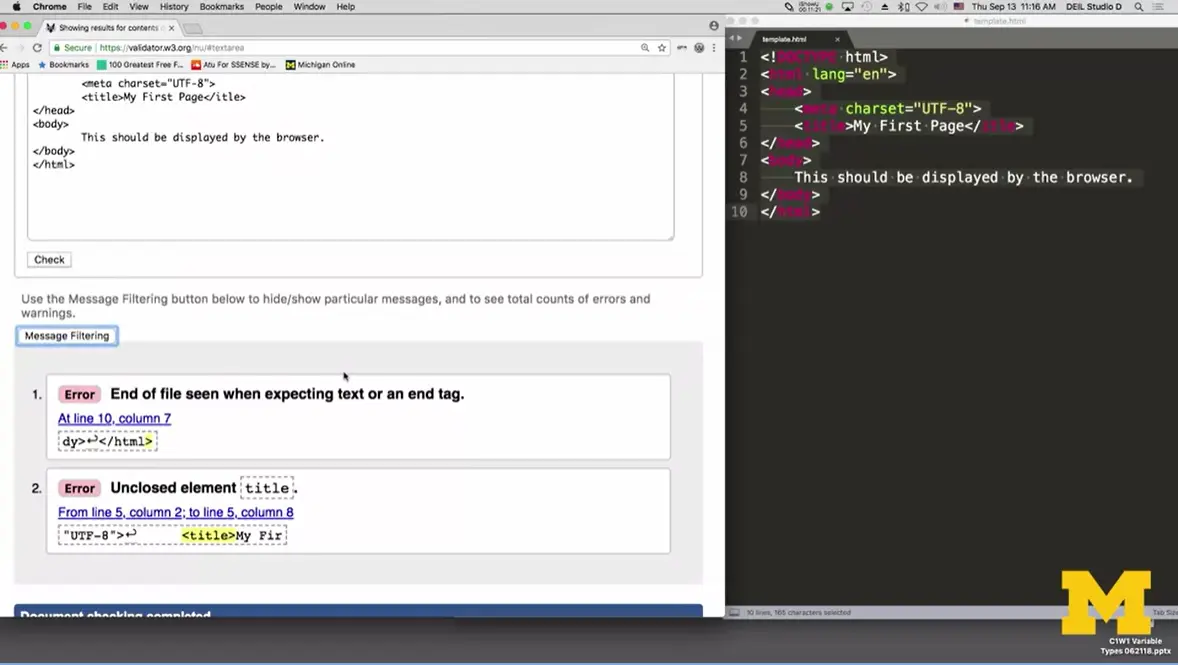

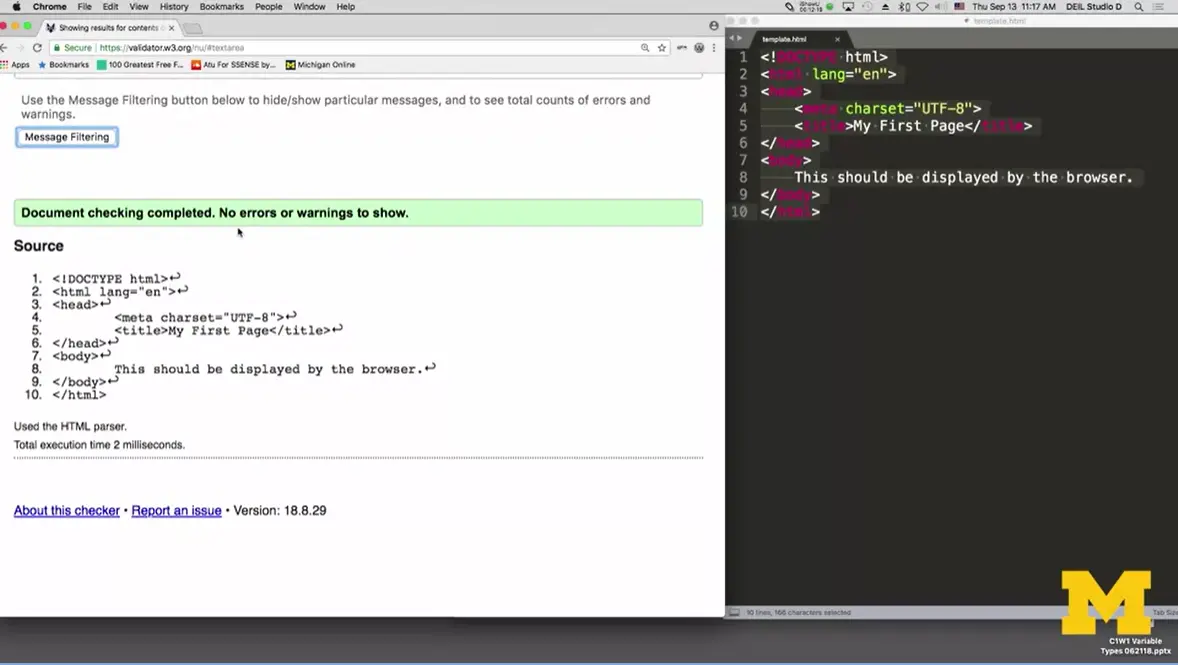

Use a validator to evaluate their code.

Identify the difference between syntax and semantics.

Identify the parts of a syntactically correct HTML page.

Recognize and use common HTML5 tags.

Be aware of what an editor is and use one.

Learn about how the web works.

Describe how and why HTML has changed.

Welcome to Introduction to HTML5. This course is an introduction to how web pages are created, sent across the Internet, and viewed on your computer, tablet, or smartphone.

This course is meant for the absolute beginner, but also touches on information that may be new to someone who has been using HTML for some years. In particular, the new options available in HTML5 and some recommended policies for making sure that your page is accessible.

HTML stands for HyperText Markup Language, a way of marking up files so that browsers (Chrome, Safari, Edge, etc.) know how to display your content as a web page. HTML uses tags to distinguish between content (what the user should see) and the instructions for displaying them (make this a list, make this a link to a different page, show this picture, etc.) There are so many things you can do with HTML. While it is possible to make a long list of HTML tags, this approach won't help you as much as practice with a smaller subset. Therefore, we focus on the following:

What HTML is and how we got from the original version to HTML5,

The "magic" behind the Internet and how your web page isn't just one file, but many pieces put together by your browser using something called the Response/Request Cycle,

The syntax behind the tags - how to write good syntactic HTML,

The semantics behind the tags - some tags have special meaning and are extremely useful if you want to make your pages accessible. Accessible pages are ones that can be accessed by the widest range of people and that includes those who have physical or cognitive disabilities, and

Getting your page on the web - This class will not require you to post your site on the Internet. However, you will learn how to publish your site if you choose. (And we hope you do and share your work with me and others in the class.)

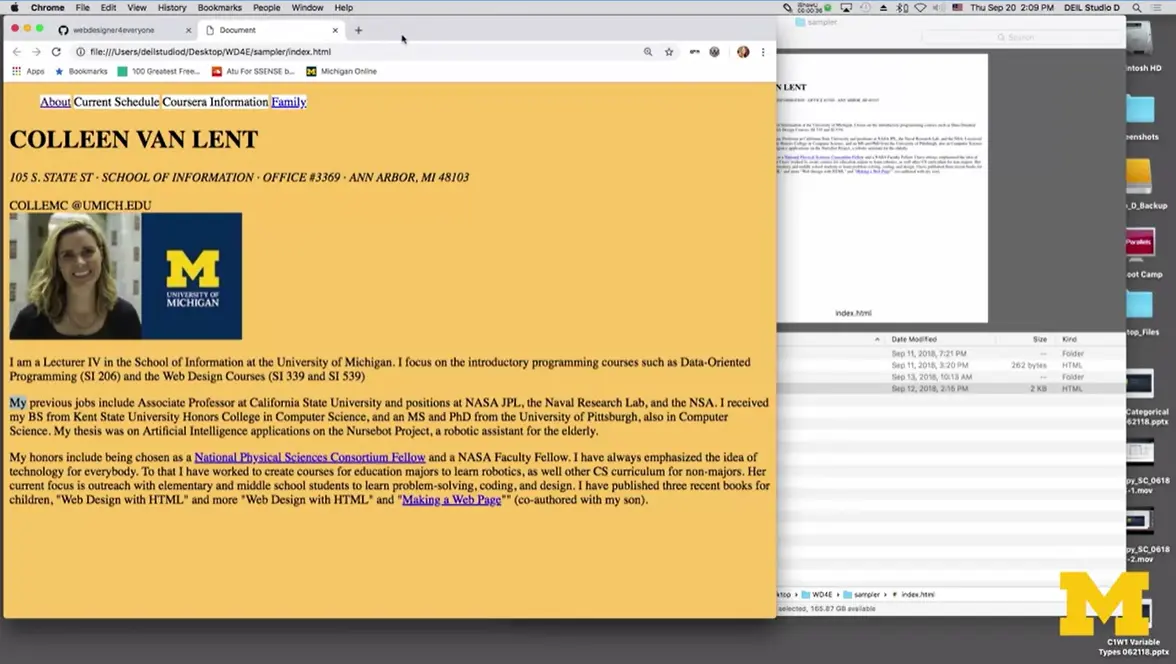

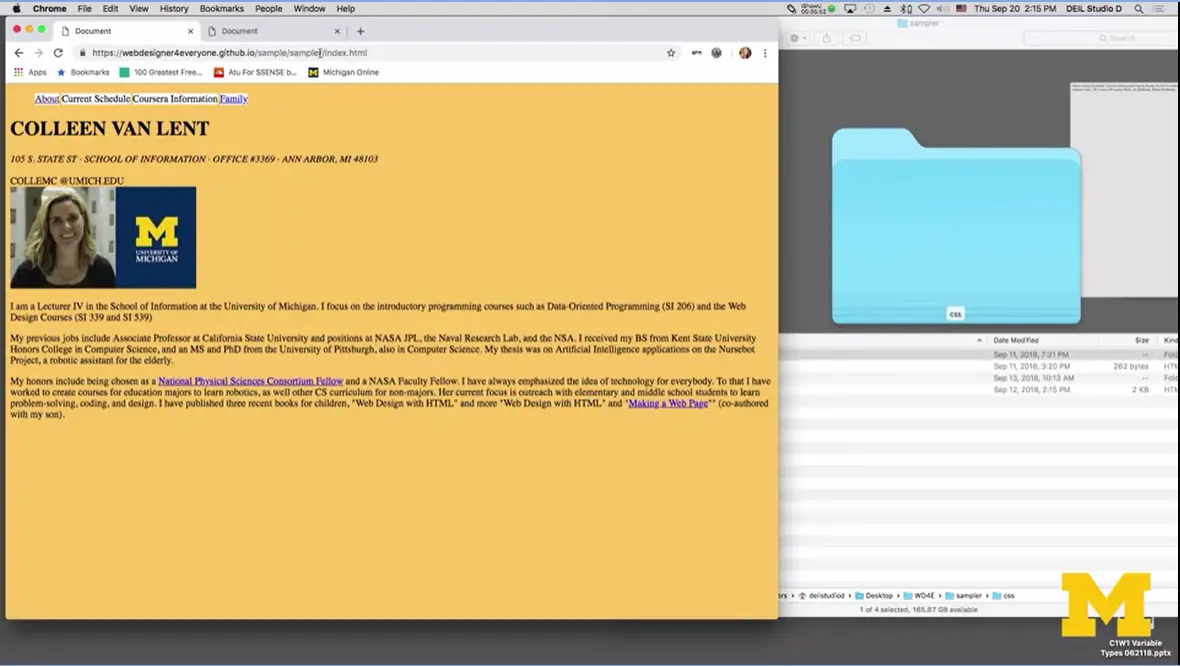

Throughout the entire course there will be an emphasis on the importance of good habits and examples of potential pitfalls. This course is about learning the proper syntax of HTML5 and styling is not covered. You can see an example Web Design for Everyone site for reference. However, upon completion of this course you will be ready to take the next course in this Web Design for Everybody Specialization, Introduction to CSS3.

Engaged learning looks different for everybody. In this course, we hope you will define your own measures of success and engage with the material in a way that best suits your needs. We recognize and celebrate the diverse ways learners engage in courses. As you go through this course, we hope you will reflect on your unique skills, needs, and aspirations, and engage in the course material in a way that aligns with your own goals. While the course provides time estimates for completion, you should feel empowered to engage in the material in whatever ways make sense to you.

We expect everyone to be mindful of what they say and its potential impact on others. The goal is to have respectful discussions that do not violate the community space created for these conversations. Here are some productive ways to engage in this course:

Participate: This is a community. Read what others have written and share your thoughts.

Stay curious: Learn from experts and each other by listening and asking questions, not making assumptions.

Keep your passion positive: When replying to a discussion forum post, respond with thoughts on what was said, not about the person who posted. Avoid using all caps, too many exclamation points, or aggressive language.

We expect all learners to abide by our full Learner Engagement Policy. We will specifically be monitoring this course for language that could be considered inflammatory, incivil, racist, or otherwise unacceptable for this learning space, and we will remove language deemed such.

Note regarding “study groups” outside of the platform: While learners are encouraged to interact with one another using communication tools offered within the learning platform, note that any study groups formed outside of this platform, such as over social media or communication applications and websites (e.g., WhatsApp) are not affiliated, endorsed, or moderated by the University of Michigan. If you receive an invitation to an outside study group mentioning the course and claiming to have any official connection to U-M or individual instructors, please exercise caution as this may be an attempted scam.

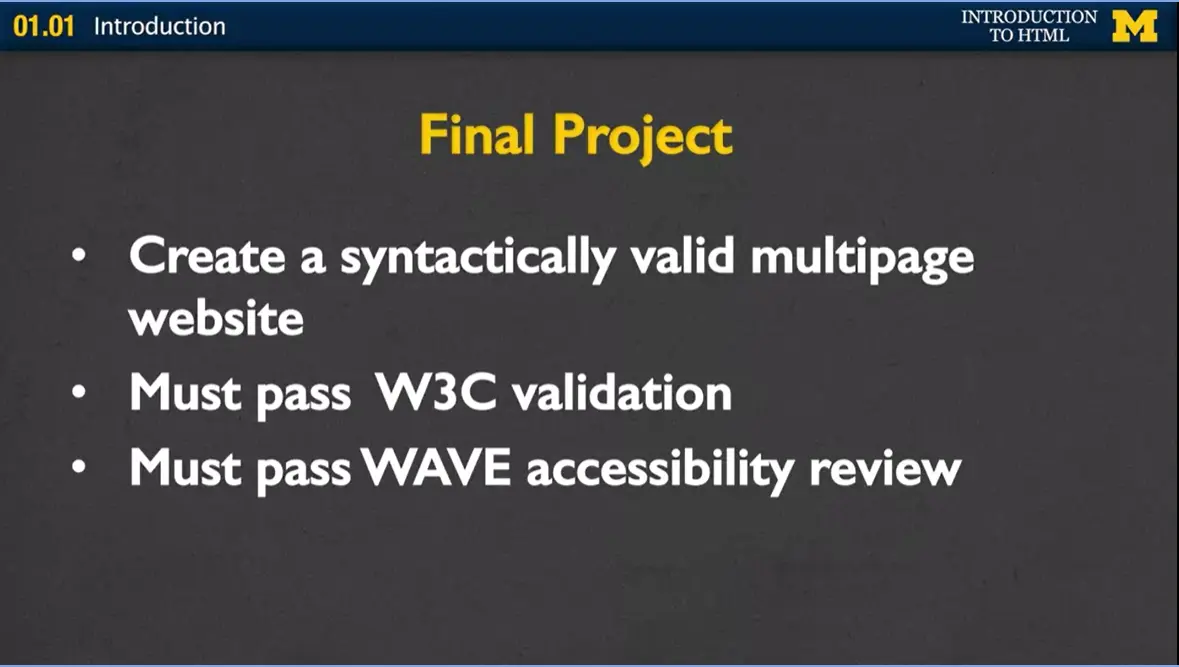

This course will culminate in the creation of an HTML document. You will be provided with an example document and asked to style it. This will not be a creative project, rather one that shows you can write syntactically correct code. You can see an example Web Design for Everyone site for reference. We will be peer grading this assignment which means that you will grade the code created by your fellow students and they will grade yours. But don't worry, we all want each other to succeed in my courses!

All submitted work should be your own and academic dishonesty is not allowed. Academic dishonesty can be defined as:

Copying words, ideas, or other materials from another source without giving credit to the original author

Copying answers or copying from your peers within the course

Employing or allowing another person to alter or revise your work, and then submitting the work as your own

Using Artificial Intelligence tools, such as ChatGPT, to create or edit your work and submitting that work as your own, unless you were instructed to use AI as part of the assignment

This course assumes absolutely no previous knowledge. In each module you will be asked to do the following:

The information has been broken down into pieces to help you learn the material in the smallest chunks that still give you enough information to do something with it. The goal is to give you the ability to listen to these during any time you have. You will find that some of the videos have material that makes sense to you at once. Sometimes you may want to replay other videos to clarify the material.

Some of the videos are not traditional lectures, instead they are videos where I demonstrate the concepts from an earlier lecture. I highly recommend that you code along with me while you watch these videos. [The key to success in this course is in writing code.] I put these videos in so that you have something specific to practice. It is also a great way for you to see how often I mess up when I am coding!!

You may find that you can speed the videos up and still retain the information. On the other hand, my mom is always telling me I talk too quickly so you may want to slow the videos down. The important thing is to find something that works well for you. Use the in-video quizzes to help you gauge how your learning is going.

Each week will include reading material. It is impossible to learn everything you need to learn just by listening to the lectures. Some of the material will come from a (free) online textbook. Other material will be other online readings.

There will also be optional material provided in many of the weeks. These may range from links to recent articles to videos on pioneers in the fields of design and accessibility. None of these materials will be required for the quizzes, but rather provide additional ways for you to branch out and learn more about the history of the field or the emerging ideas.

Questions and discussion of course material should take place within the course itself. Please do not contact instructors or teaching assistants off the platform, as responding to individual questions is virtually impossible. We encourage you to direct your questions to the Course Support Discussion Forum, where your question might be answered by a fellow learner or one of our course team members. For technical help please contact the Coursera Learner Help Center support forums.

We are committed to developing accessible learning experiences for the widest possible audience. We recognize that learners with disabilities (including but not limited to visual impairments, hearing impairments, cognitive disabilities, or motor disabilities) might need more specific accessibility- related support to achieve learning goals in this course.

Please use the accessibility feedback form to let us know about any accessibility challenges such as urgent issues that keep you from making progress in the course (e.g., missing or inadequate alt-text, captioning errors).

Third-party sites and software: While the University of Michigan is not responsible for the accessibility of third-party sites or applications that may be linked from this course, we still encourage you to report associated third-party accessibility issues so that we can ensure you are able to participate. In such cases, we may contact you for additional information as we investigate ways of removing accessibility barriers or to suggest accessible alternatives.

We welcome all learners to this course. People like you are joining from all over the world and we value this diversity. We strive to create a community of mutual respect and trust, where people from all backgrounds, identities and views are valued and heard without the threat of bias, harassment, intimidation, or discrimination. We pay attention to your feedback, how different types of learners experience this course, and aim to make improvements so the course can best serve everyone. We hope you enjoy learning about topics that are important to you.

Below is a list of technologies that you will use to participate in this course. I recommend that you spend time reading the brief description of each technology before jumping into the course. By doing this, you will have a better idea of what to expect and can create a plan for how you will approach taking this course.

If you are new to Coursera and you want to familiarize yourself with the platform, read the Help Articles in Coursera Help Center. This is a good resource where you can find answers to many basic questions such as how to adjust video settings, how to submit assignments, and how to gain a course certificate.

This course uses a sharing tool called the Gamut Gallery. Throughout the course you will be asked by your instructor to create your own work related to the course content. The Gallery provides a digital place to submit and share your own work, receive feedback, and pose questions to other learners about their work. It will appear as an item titled, “Ungraded App Item.” For more information about this tool and its use in our courses, please see the Center for Academic Innovation’s Software Terms of Service.

In this course we will assume that students will use Replit to host their code. Replit is an online Integrated Development Environment (IDE) for writing and sharing code. Once you get the hang of using Replit you will be able to easily share your code and your deployed website sites with your family and peers. However, students may choose other hosting options if they prefer.

If students choose not to use Replit, they will want to have an editor to create their code. Two common editors that you will see used in this course and by others are Sublime and Visual Studio Code (also called VSCode). Both of these programs are free to download and use and there are also many online tutorials available to help learn the software.

Replit has free hosting built-in – they will often refer to it as "sharing your repl." There are other free hosting services as well, including using Github Pages. Learning to use Github Pages can take some time, but is a useful skill for advanced learners.

Hi, I'm Colleen van Lent and I'm happy to welcome you to Introduction to HTML5. I am very excited to teach this course because I love the idea that we finally will have some course that really will explain the basics to as many people as possible. I love working with people and I love working with technology and I think the best thing we can do is have as many people involved as possible to really make sure that we're building things that everyone can use.

In this course, we will be covering the basics. I really can't emphasize enough that we will be starting at the very basic building blocks.

We'll start off talking about what's called syntax and semantics. What is the actual code that people write in order to make a webpage a webpage? Are there any special meanings behind any of these words that can convey special information to those who may not be able to access the web the same way I do? Perhaps, someone who uses special accessibility tools.

After we cover the syntax and semantics, we're going to talk more about this accessibility idea that I just alluded to. This idea that if we're going to build a webpage, what do we need to do to make sure the most people as possible can access the information?

We're also going to be talking about getting started in technology and writing code. When I mean talking about getting started, I mean really talking about getting started, right down to you and I are going to walk through together on how we're going to create a file. One of the things I think that really trips people up when they're starting to learn computer science or any type of technology-based criteria, or curriculum, is that professors or instructors say let's get started, here's your homework. Go ahead and do it and everyone just kind of stops because they're not sure where to get started. I really want to be there for you to show you how to get started and get off on the right foot.

Let's talk about what we'll cover in this course. In Week One the focus is on questions. It's not on coding, it's on questions. I want you to understand what happens when you type something into the URL. If you type in www.introwebdesign.com, how is this page magically appearing in front of your browser? I also want to talk to you about what types of tools you are going to need in order to code.

We're going to talk about editors and browsers and other different software tools because I want you to know right from the start what you're going to need in order to succeed in this class. Finally, we're really going to talk about HTML5. What happened to HTML1? What happened to HTML2? What is this evolution of what's going on with web design and the languages we use? In Week One, again, almost no coding. Really, just giving you an idea of how the web works and why it's important for you to be able to interact with people and with code that's being used to create your sites.

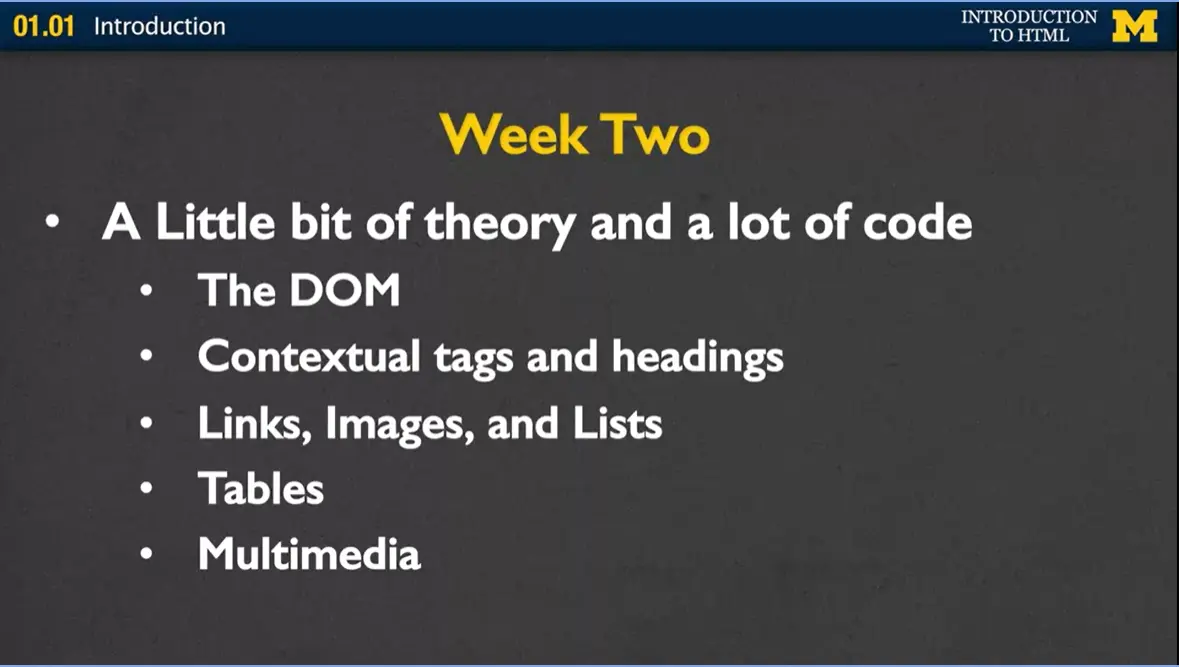

Week Two, we're going to talk a little bit of theory, and then, unfortunately for some people, a lot of code. There's this idea of something called the Document Object Model, upon which all webpages are built. If I can get you to understand just a little bit about that, then later on, if you decide to go off and use WordPress or some other software to make your own website, you're going to be able to really understand what's going on so much better.

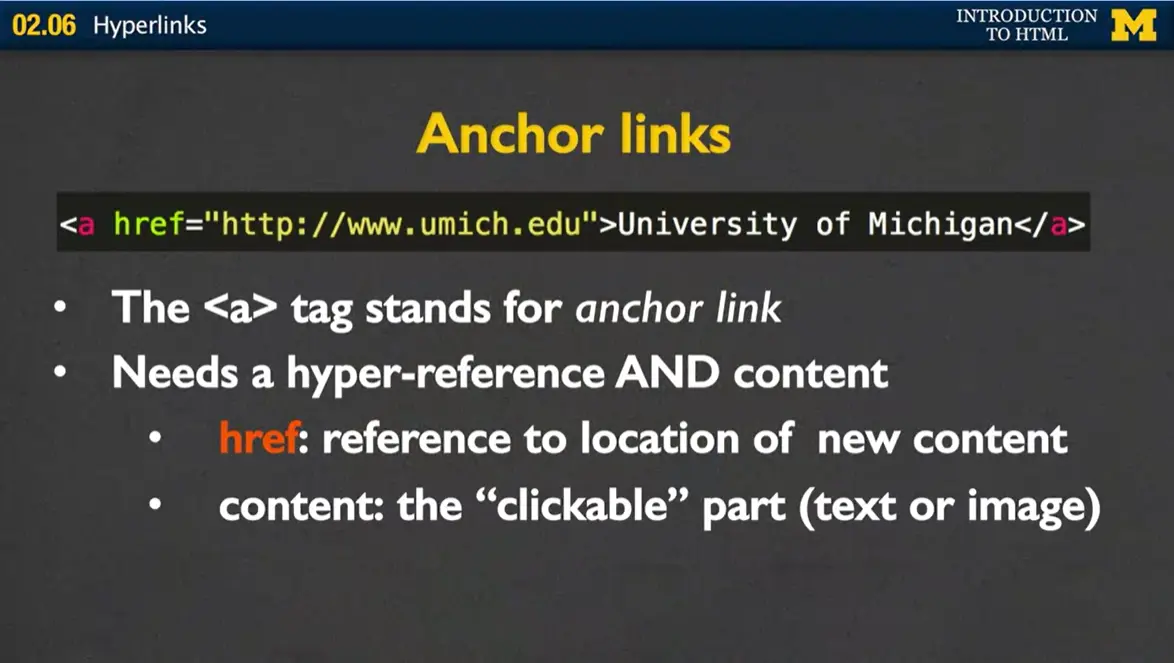

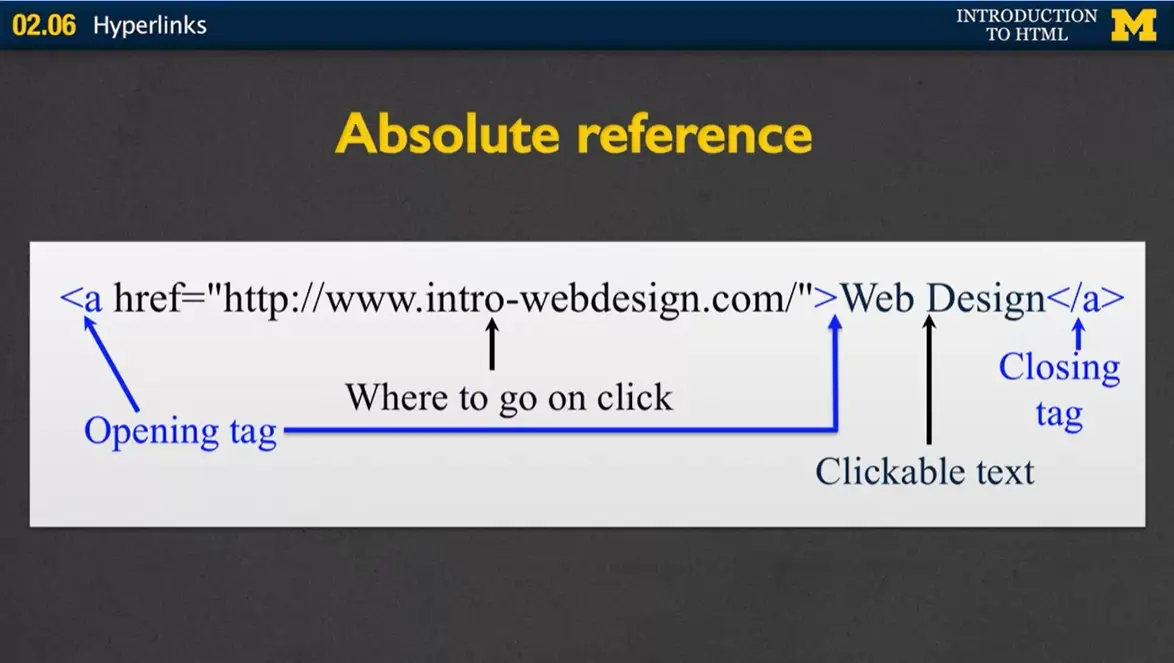

We're going to talk about things called contextual tags and headings and different things we can use to make our site have different meanings and different appearances. We're going to talk about links, images, lists, tables, and also multimedia in case you would like to add any video or audio to your site.

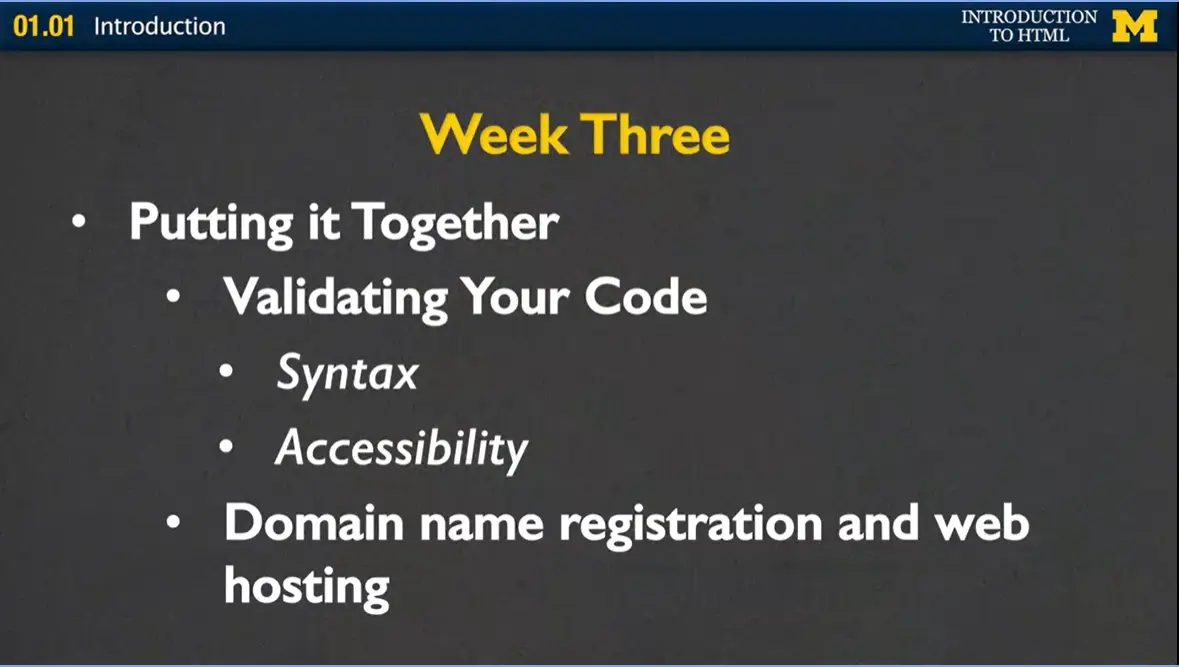

Week Three, we're really going to put it all together. At this point, you should know just enough about HTML5 where you'll be dangerous. Where you can create something that works but doesn't work all the time. In Week Three, we're going to put it together, and I'm going to talk to you about some of the things that are often overlooked, such as validating your code. How can we make sure that the code that you wrote doesn't just look good, it's syntactically correct? It's going to work everywhere. Again, when we validate your code, we'll talk about the syntax but we'll also talk about accessibility, which is hey, we validated your code to make sure the rules are there. Let's also validate and make sure that the meaning is there, as well. Finally, we'll talk about what's called domain name registration and web hosting because it's a lot more fun to make websites if you can actually put it out there on the internet and let your friends and family see it, as well.

Finally, we'll work on a final project where you'll put together a lot of different things that you've been learning. You are going to create what we call, syntactically valid multipage website. Your site will have at least two to three pages. After you've done your coding, you'll run it through to make sure it validates and it's very accessible.

Your final project is actually going to be something that's a little bit ugly, I'm going to admit to right now because we're not going to be talking about styling, we're not talking about different things. I really just want you to understand the HTML5 language and that's all about content.

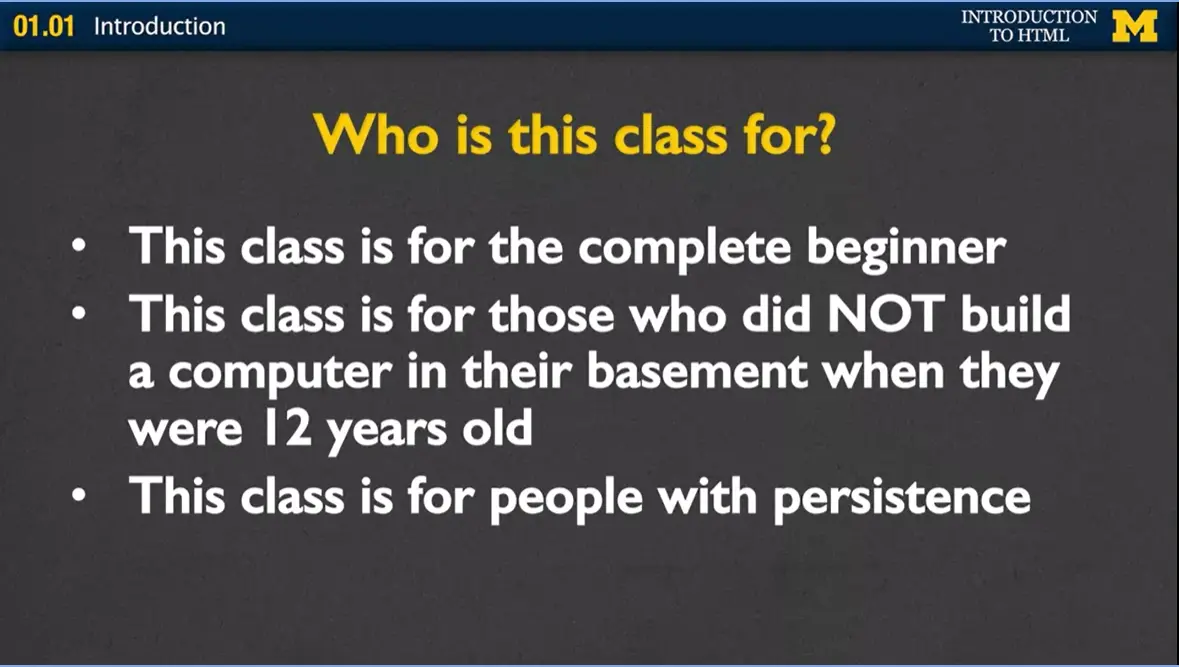

Let's talk logistics. Let's talk about who this class is for. Who am I aiming for my star student? I'm really looking forward to teaching the complete beginner.

This class is not for those people who were building a computer down in their basement when they were 12 years old. You are very welcome to hang out with us but we are really here to talk about how we, through persistence, can create a website. One of the things that I'm kind of anti about is the word passion. Now, I'm passionate about teaching you this material but I don't really feel like you need to be passionate about technology or passionate about computing to really get a lot out of this class. Instead, it's about persistence. I'd like you to just hang in there and learn enough that you can go off and help people build better technology.

A little bit about of who I am, I have a PhD in computer science which is really the least important part of my qualifications to teach this class. Instead, I have two decades of teaching experience and I've taught a wide range of different students. My emphasis is always been on education and I'm somewhat famous for running around the classroom helping people debug their code, finding out what's going on here, finding out what's going on there. This whole idea of teaching this class is kind of novel to me because I am sitting here not moving. The important part is that I really do care about people succeeding and I am hoping that I can help you take your skills to the next level.

Here is what everyone wants to know. In this class, what kind of workload will there be and how will you be evaluated? There are going to be weekly videos. Some of them are like this, a lecture format. You should really feel free to watch them anywhere but I also like to include some videos that are going to be much more demo format. By that, I mean you want to watch the video with a computer next to you, so you can type along and test it out and try it.

There will be weekly readings. Most of them will be from a free online textbook but there may be some other online articles I include as well, if I happen to come across something that's very timely for what we've been learning. There will be weekly assessments, typically, in the form of quizzes. There will be that final project and I put in here warning; it will be ugly. I don't mean that the process will be ugly. I think you'll find it very straightforward. It's just again, I can't emphasize enough that this class is about the language HTML5, it's not about creating beautiful sites. It's about you really learning just the building blocks and it's always so much easier to build something ugly the first time than build something beautiful.

How will you succeed in this class? In a perfect world, you would be coding with two or three other people and you'd be talking and you'll never be coding alone. I'm hoping that you'll create a community, probably through the message boards. I need you to work smart. One of the things that kills me is when people say I spent three or four hours working on this. I never want to hear that from a student. Instead, I feel that if you've ever run into a problem when you're coding, you should stop after 10, 15, 20 minutes max and go walk away. Go get help from someone, take a break, think about something else. It's all about working smart, not necessarily hard. Next, you really need to learn how to look things up on your own. There is no way I can teach you everything you need to know about HTML5, and you wouldn't want me to, it would be very boring. Instead, you need to feel the confidence to go out and use search engines to look up the topics that you're interested in.

My job is to give you those key words and key ideas so you know what it is you want to search for. Finally, you really need to practice, practice, practice. You will not succeed in this course unless you've written the code yourself and really tried to muster your way through some of the mistakes and typos that you're going to have. Let's just review. Once again, this class is for beginners, and I'm excited to have you join us.

When you're done with this class, you will have the ability to write and understand HTML5 code. You're not leaving as a developer but you are going to leave as someone who understands code. Finally, one of the key things that I'm going to stress throughout this whole course, is that you will understand the importance of accessibility in technology. If when this course was done, I had even one student who said, hey you know what, I'm going to go on and I might not be a coder but I am going to go work with somebody else to help make their code more accessible, I would be thrilled with that. Welcome to the course and I hope you have a lot of fun as you learn more about HTML5.

It is really difficult to find a textbook that focuses on just the basics. In the past I used a textbook that covered too many "extras". The new version of this course (and the entire specialization) will be using two online resources.

The first resource is a big-picture tutorial from Shay Howe called Learn to Code HTML & CSS. You can also purchase a paper copy of the book if you prefer, but everything you need is free and online. This book isn't perfect - it covers more than I would like to cover but it is a really good start. I do my best to direct you to sections that most closely follow what I will be covering in each video lecture.

The second resource is the W3 Schools tutorial. This tutorial is more of a dictionary of terms where you can quickly find specific topics.

While you are reading, make sure to look closely for code. The Shay Howe site uses CodePen - a tool that lets you see the code and the output. Clicking on the code will also take you to the CodePen site where you can try changing the code to see what happens. W3Schools has a “Try It Now” option. Many students really appreciate the ability to change existing HTML code and see (immediately) what it does. So if you would like the ability to write and test snippets of code, this is a good resource. Don't forget that you still need to validate your code.

The preferred way to code in this class is editor software (Notepad, TextWrangler, Sublime, etc). Recently I have been using Visual Studio Code and I really like it. The software is free and works on most types of computers. If you are a paid learner you will want to use Replit.

The textbook I link to throughout the course has nice, short chapters that go well with nice short lectures. These other (free) online resources are just as good if not maybe even a little better in some cases. So feel free to read them now or at the end of the class to help reinforce what you learn over the next few weeks.

If you are looking for even more hands-on practice many people use the Codecademy website. This site awards badges as you complete skills. This site is free, but registration is required. My advice is to make sure you are doing more than just trying to "get through," and focusing on the concepts that you are practicing.

At the site linked below, you will find html files discussed in the lecture videos.

Files with all the code and other text discussed in the videos are available in the resources section of the course. These are available in pdf and docx format.

To support learners, accessible lecture slides are provided as downloadable PDF files below, and individually within each lecture video. Please note, sometimes the slides will look slightly different from the videos since I like to update the slides when things change. For instance, when I first created this course Internet Explorer was a very popular browser. It has been replaced by Edge.

Week 1 Lecture Slides.pdf

Week 2 Lecture Slides.pdf

Week 3 Lecture Slides.pdf

To support learners, accessible lecture slides are provided as downloadable PDF files below, and individually within each lecture video. Please note, sometimes the slides will look slightly different from the videos since I like to update the slides when things change.

Whenever possible, the code is linked through CodePen, Replit, and a downloadable zip file. You can choose the format that best suits your learning style.

You can find the code at HTML5 Course Code. It is organized by week, so you can check to see if any code is provided for this week's lessons.

Hi. Today we're going to be talking about HTML5. Specifically what it is, and why we aren't learning HTML1 instead. So what is HTML?

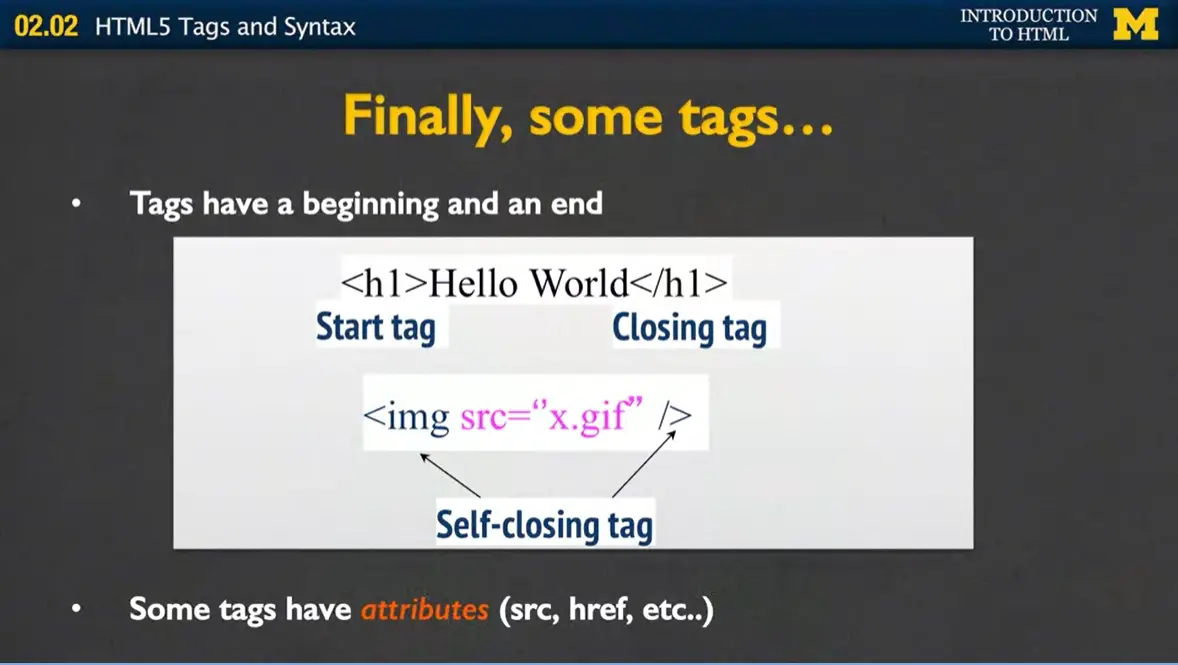

HTML stands for hypertext markup language. Markup languages are actually very common. They're not the same as programing languages, instead they're special languages that use tags to annotate or markup documents. In HTML, the tags tell the browsers where you want to put headings, images, lists, links, et cetera.

A .HTML file is a special kind of file. You've already seen special file extensions before. Whenever you open a file that has a .doc, your computer knows to open it in Microsoft Word. If you see a file with .ppt your computer knows, that's a Power Point file, I should open it in Power Point. In the same way, when you computer sees the .html file, it knows that it should open it in an internet browser such as Chrome, Firefox or Safari. Your browser can read this file and it knows how to display it on the screen. It's more than that, HTML file tags also allow screen readers and other assisted devices to utilize the tags to present the information in new and special ways.

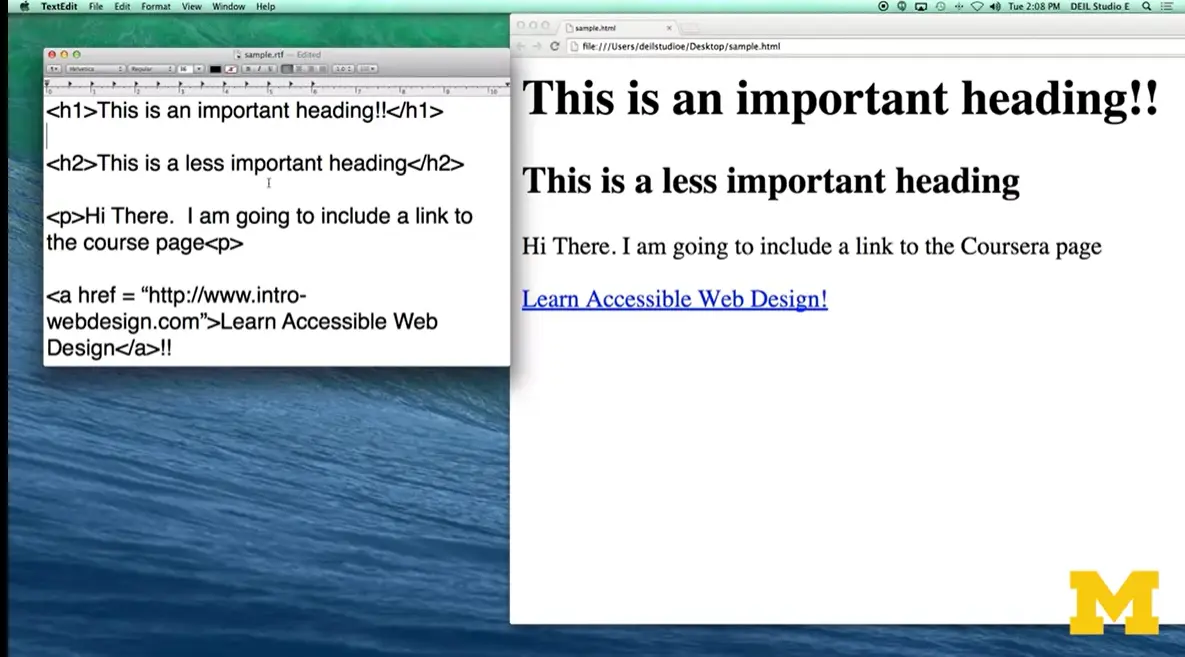

So HTML is very similar to English, you can understand it even if you don't know much about it.

Let's look at this example HTML file over here. Most of it is just a typical English language. This is an important heading or h1 there. I am going to include a link to the course page. But if you look closely, you can see we've added these little tiny tags that the browser use this to know how to represent the material. So, h1 is just the heading tag. It says to the browser, hey this is something really important. I want you to put it in bigger font, and also if someone is using an assisted device, I want them to know if this is something important. h2 also displays some sort of importance, but not as much. I have a p tag for a paragraph, and I have another tag down here called an anchor tag. To let the browser know, I don't want you to just show this material, I want you to actually link it to a different web page. So here's the output when any browser would look at our code.

In the beginning, learning HTML is mostly about learning all those different tags that I showed you in that file. This is called learning the syntax. It's how you learn which brackets to use, backslashes, and different things like that. You spend most of your time going, oh, did I remember that tag and did I write it the right way? That's very short-lived.

In just a little amount of time, you're gonna gain the confidence to not worry about your syntax and instead to be thinking about the semantics or the meaning behind the tags. How important is this information that I'm trying to get across, and is this the right tag to be using? If someone's searching my page, can they find what they're looking for? Even if they can't see the text, can they use the tags to navigate through it?

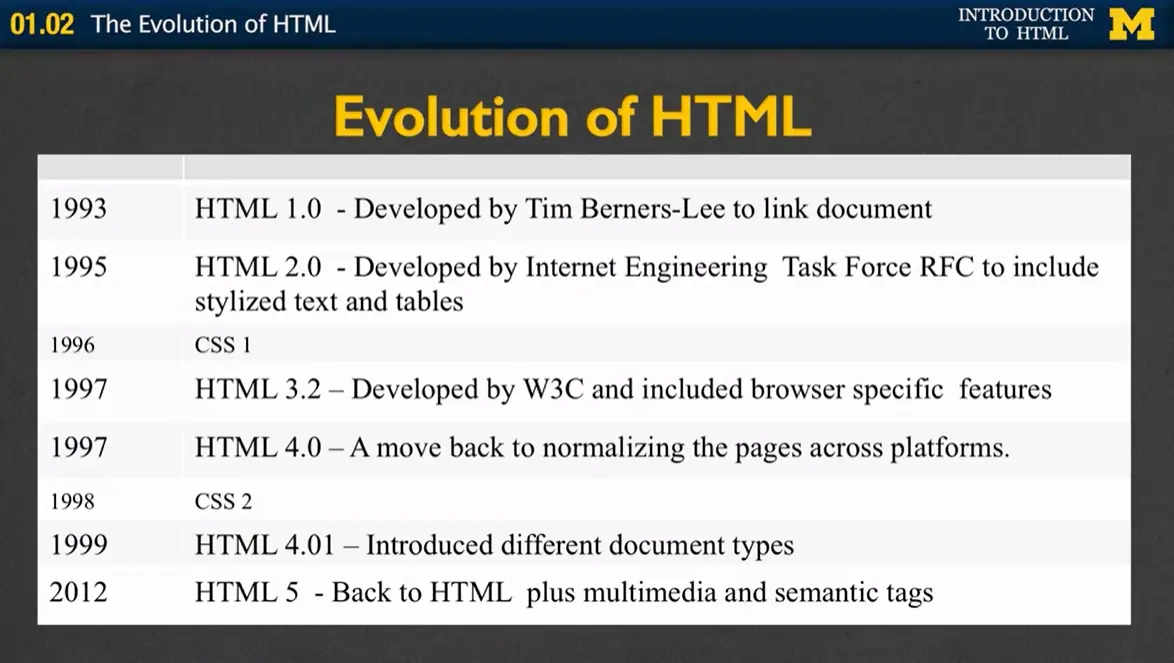

So what happened to HTML1? Why are we using something called HTML5? Well, let's talk about the early years. HTML was created in 1990 as a way to electronically connect different documents via hyperlinks. Hence, this idea of a web of connections. What was happening, is that scientists were using the Internet to list their different research papers, and you would have a long list, each paper independent of the other. But, HTML, gave you ways that you could read a paper, and right within the text, link to another exciting physics paper. Because the audience from HTML tended to be people like my dad up there in the corner, they were nuclear physicists, they didn't care about things such as color, images, or anything that wasn't science related, and that was the key.

HTML was intended to work across any platform. And in order to do this you really had to avoid things such as special fonts or different colors or anything that was more about layout than content.

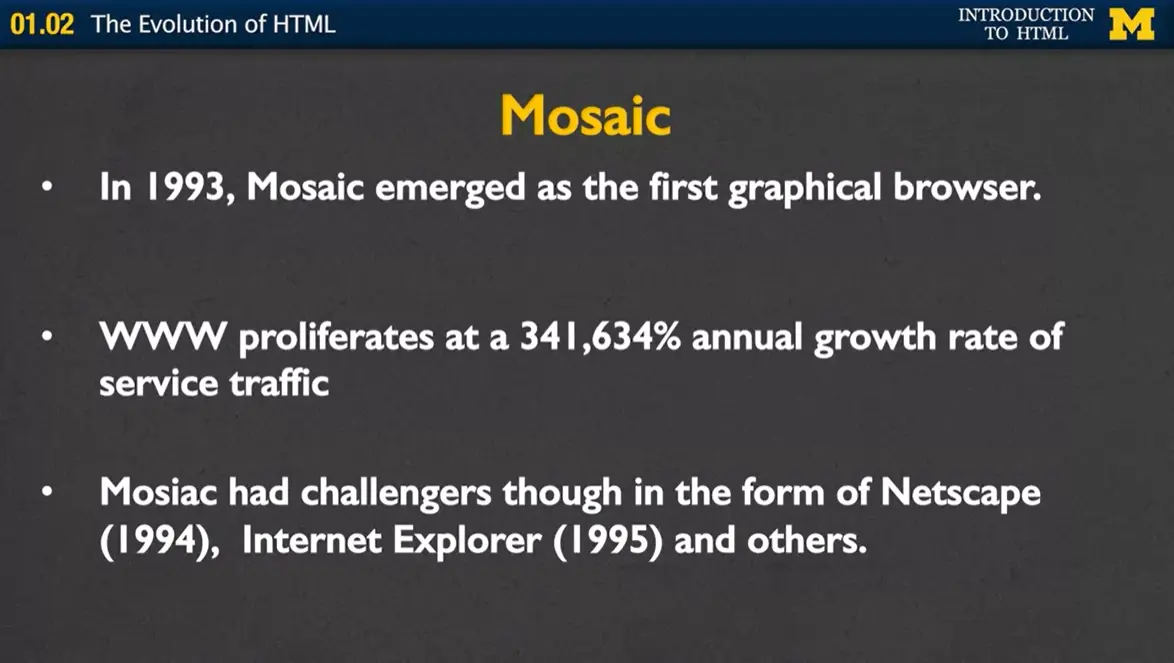

However, in 1993 Mosaic emerged as the first graphical browser. And what that means is that it was a first browser to actually introduce the idea of images and when that happened, there was a lot of debate among the research community as to whether or not this was a good thing. The pioneers really wanted to keep it simple content based, let everyone access it. But the innovators were saying no. People like pictures, they like layout. They like that even as much as they like the content. So there is a big battle between how the Internet should evolve from that point.

So after Mosaic emerged, the use of the Internet just absolutely exploded, and more and more people were using it for commercial means, instead of just for doing research. Mosaic had challengers though, in the form of Netscape, Internet Explorer and other browsers.

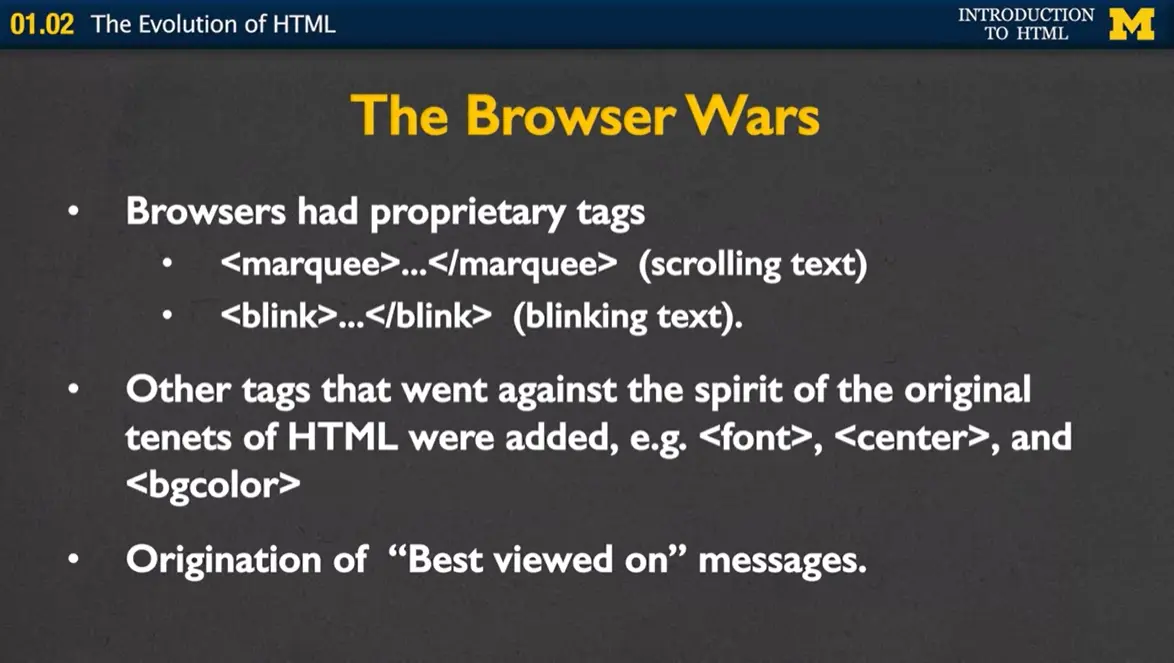

This was the start of what we call the browser wars. Each of these browsers decided that they wanted to create these proprietary tags, tags that would only work on their browser. Some of the examples were marquee, where you could have scrolling text, or blink which would only work on some of the browsers and not others.

Other tags weren't proprietary, they actually worked on any browser, but they went against the original spirit of HTML. They were tags such as font or center, for centering your text or background color. This may not sound like a bad thing, but some computers didn't have the access, didn't have the ability to have all the different colors that other computers might have. And this led to some really ugly looking pages.

That also led to the origination of what we call the "best viewed on" messages. When you went to a site you almost immediately told which browser you should really view the site on. Otherwise, you weren't going to get the optimal experience. We all in a way suffer from browser wars, or best viewed on images today. Many times when you go to a page, you'll see that you can't actually access the full content if you're on your phone, unless you click on a link to the full website.

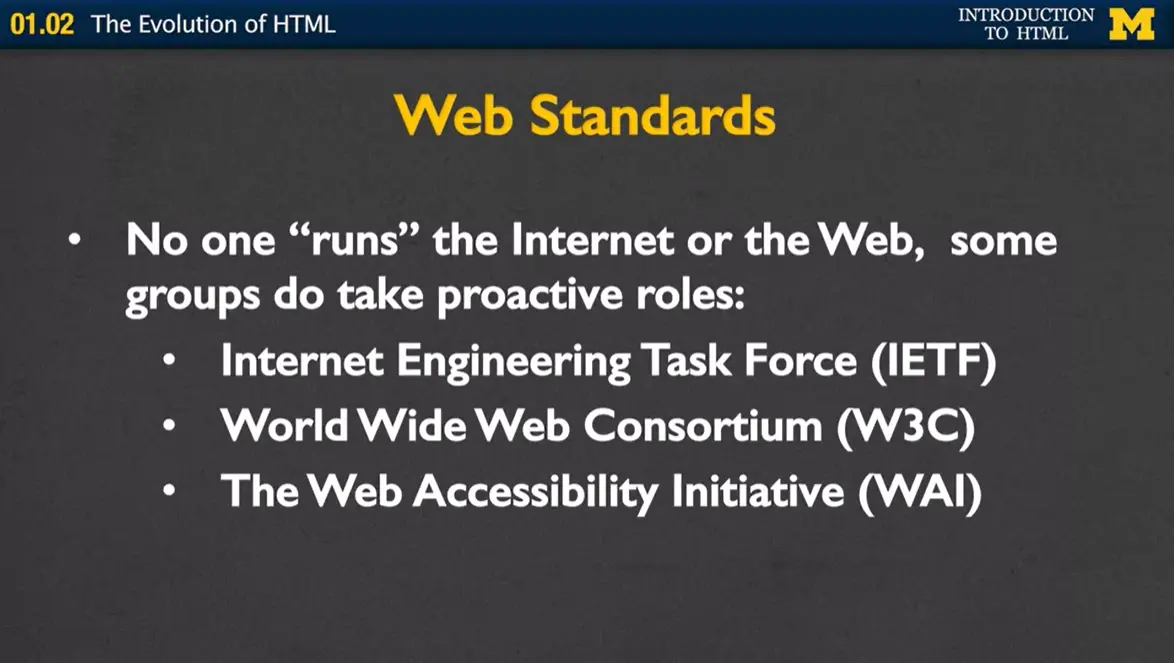

How did this happen? How did we get to the point where different browsers weren't agreeing on the different roles that HTML should play? This comes back to the idea that no one runs the Internet or the Web. However, some groups have taken a more proactive role to try to help standardize what's going on out there. The first is the Internet Engineering Task Force, they really focus on the idea of how the different networks should collaborate and how they should work together.

The second, World Wide Web Consortium, instead deals with HTML and the evolution of HTML, they want to know what kinds of tags the browsers should and should not support. Third, and last, one of the newest groups, The Web Accessibility Initiative, they want to make sure, that no matter how people are accessing the web, they have the same ability to view the content.

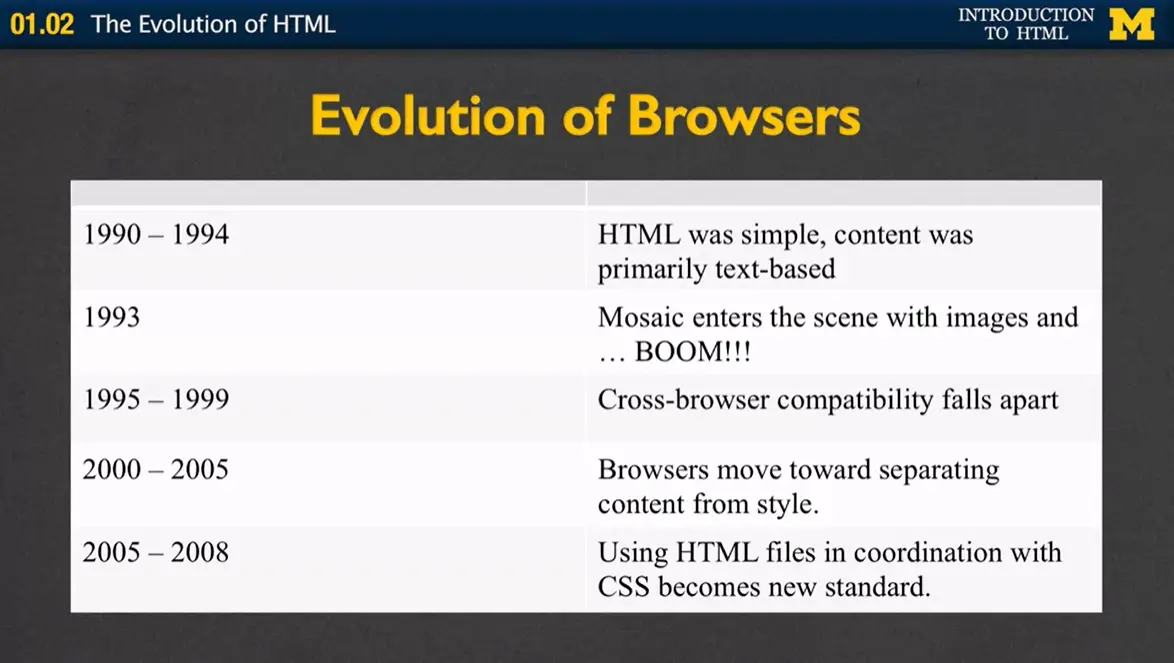

We had this evolution of browsers that we've been talking about. In 1990 to '94 it was all very simple, text-based. In '93, we talked about how the images entered the scene, and pretty much exploded the Internet. Cross-browser compatibility made many of the web pages just fall apart and led to incredibly ugly code.

In the beginning of 2000 browsers went back to this idea of separating content from style. And in 2005 it became standard practice to use HTML files, which we are learning about in this course, to create the content and CSS files to style it.

So as the browsers evolved so did HTML. The way it tends to work in most computer science and technology fields is that it's the coders and the developers who push the standards. So as coders learned that there more and more things that they wanted the ability to do, it's the browsers job to keep up.

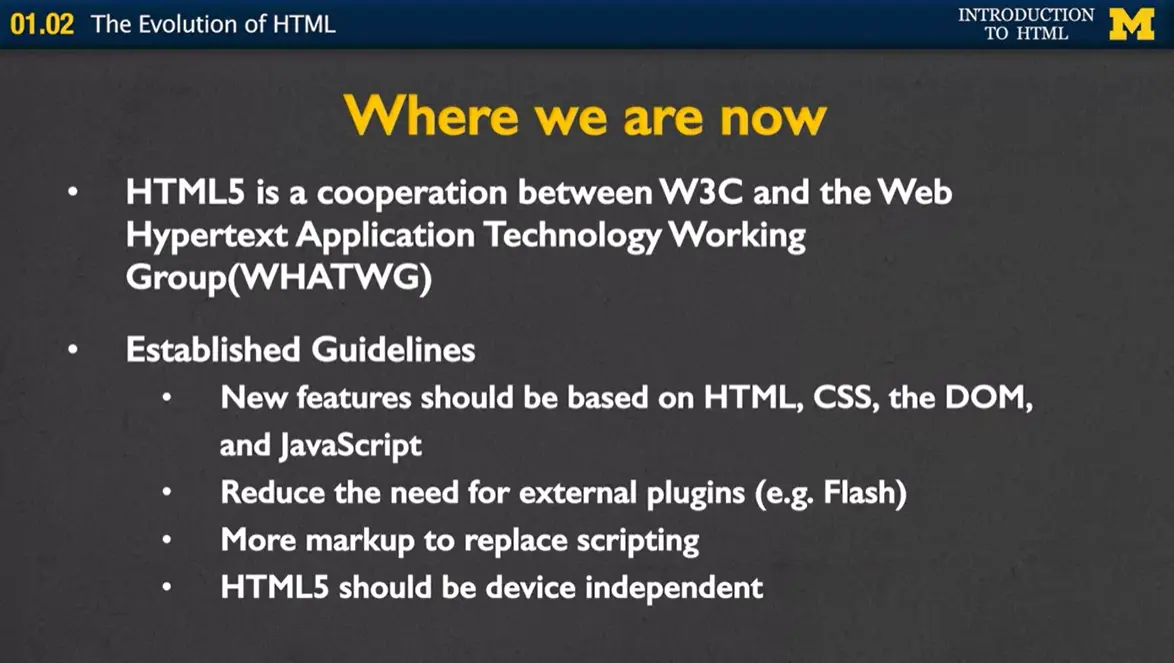

So, where are we now? HTML5 is a cooperation between W3C and the Web Hypertext Application Technology Working Group, and what they've done is they've established these four guidelines for how HTML5 should be approached as browsers go to support it.

The first idea is that new features should be based on HTML, CSS which is the styling language, the DOM and JavaScript. Nothing more. They want to reduce the need for external plug-ins, it's very frustrating when you're on a browser and you find that you can't watch the video that someone posted.

They also want to move so that mark up, or the mark up language can replace scripting. If you find that more and more developers are writing code to make something happen, get rid of the code and just make a simple tag that can do it instead.

And finally, HTML5 should be device independent. It shouldn't matter whether you're on your phone, you laptop, a PC or even on a screen reader. You want everyone the same access to the information.

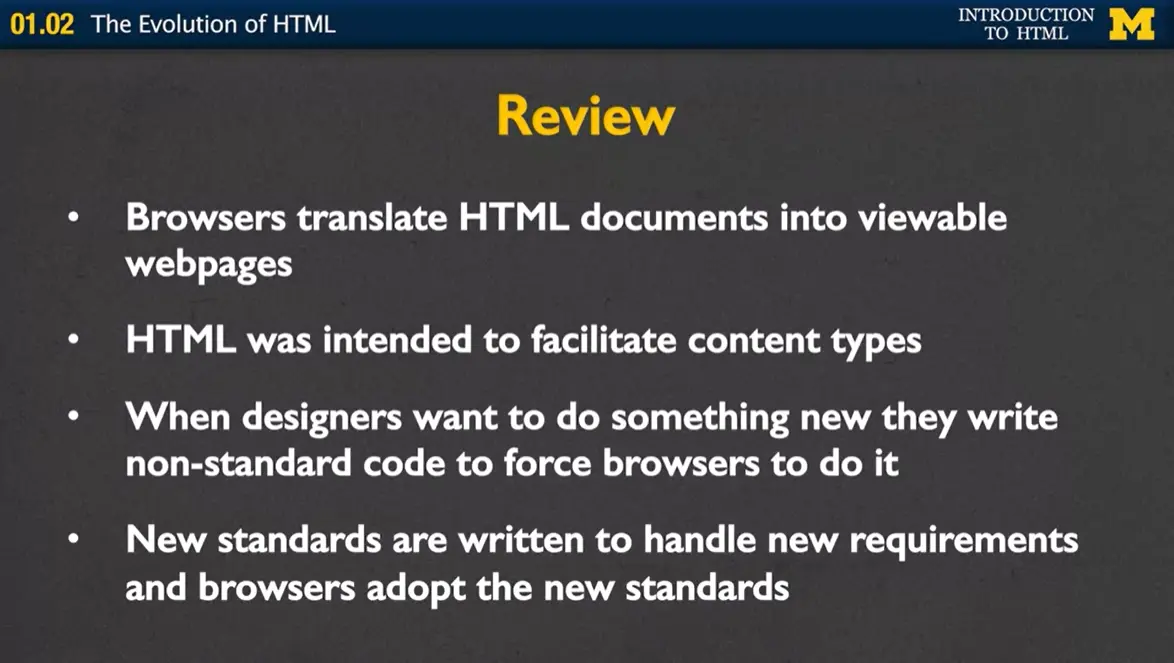

When you think back over this module, there are certain lessons I hope stick with you. The first is the idea that HTML is not a programing language, but rather a way that browsers can translate documents into viewable webpages. HTML was intended to facilitate many different content types. Images, pictures, links, lists.

What we've found throughout the history of the Internet, is that when designers want to do something they tend to write nonstandard code to force browsers to do it. So, this is why we're developing new standards in HTML5 to handle these new requirements that people desire and push browsers to adopt the new standards.

Today, let's talk about the request-response cycle or basically what happens when you type something into the address bar of your browser.

One of the things I think is really funny and I'm guilty of it as well, is that we all do things and we have no idea how they work. If I were to ask you when you type in an address, what happens? This lecture is actually one of the most technical of this entire class. I don't want to feel like you need to memorize this or write it down, but I do think it will help you understand what is going on as you learn HTML5.

One of the things you might want to understand is the client-server relationship. Servers are basically machines that hold all the resources. Our hope is that they're always connected to the network. Clients are what we're using, where the machines that you use for personal use; like laptops, phones, et cetera.

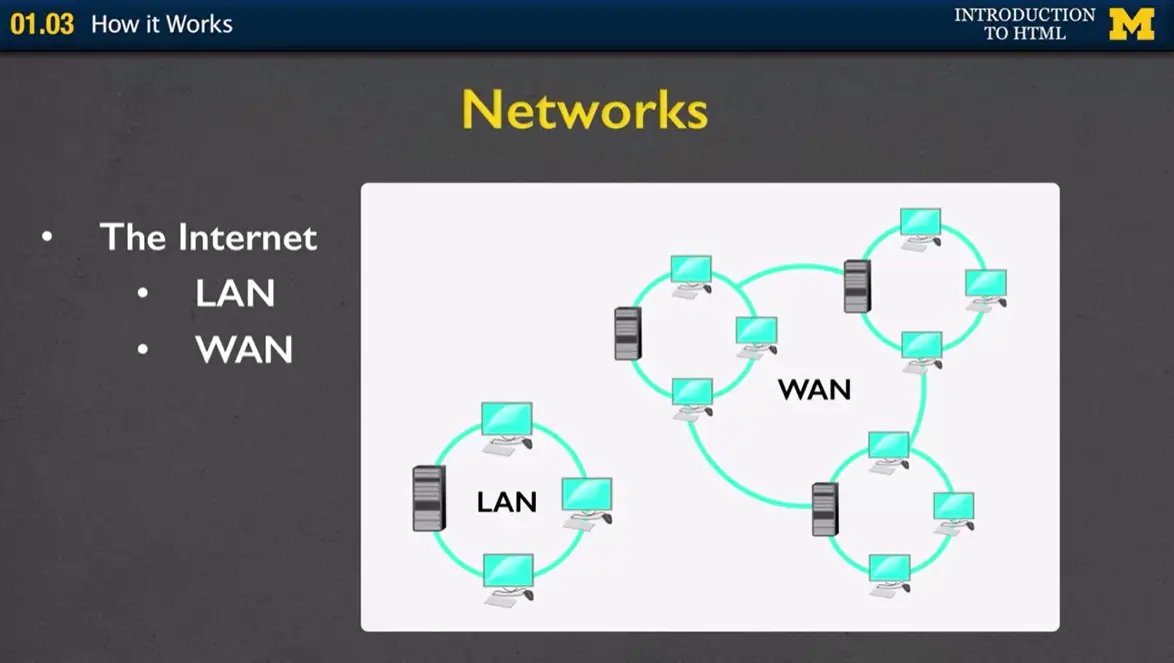

Let me show you in this picture. It's common to use networks such as something called a LAN or a WAN. A LAN is a local area network, and so what I have right here is this idea that we can have three different computers and they're all sharing one server. Why would we want to do that? Well, a lot of times, you only have one printer or one of the different resources. This way, all three machines can work together and share that one resource.

The LAN is the local area network. Sometimes, you want to have something larger or a wide area network. In movies, where the good guy is breaking into the building to steal the software, what's typically happened is they have this server that everyone who works in the building can access but no one outside the building, or you can even have it across different buildings but you don't want anyone from the outside to be able to get your information.

Local area network is like your office building. A wide area network might be a university, where you want to be able to share servers across multiple buildings. The largest wide area network is, of course, the Internet.

Now we get back to that question of what happens when you type something into the URL? What you're doing is that you the client are requesting a web page and the server needs to respond with the appropriate files.

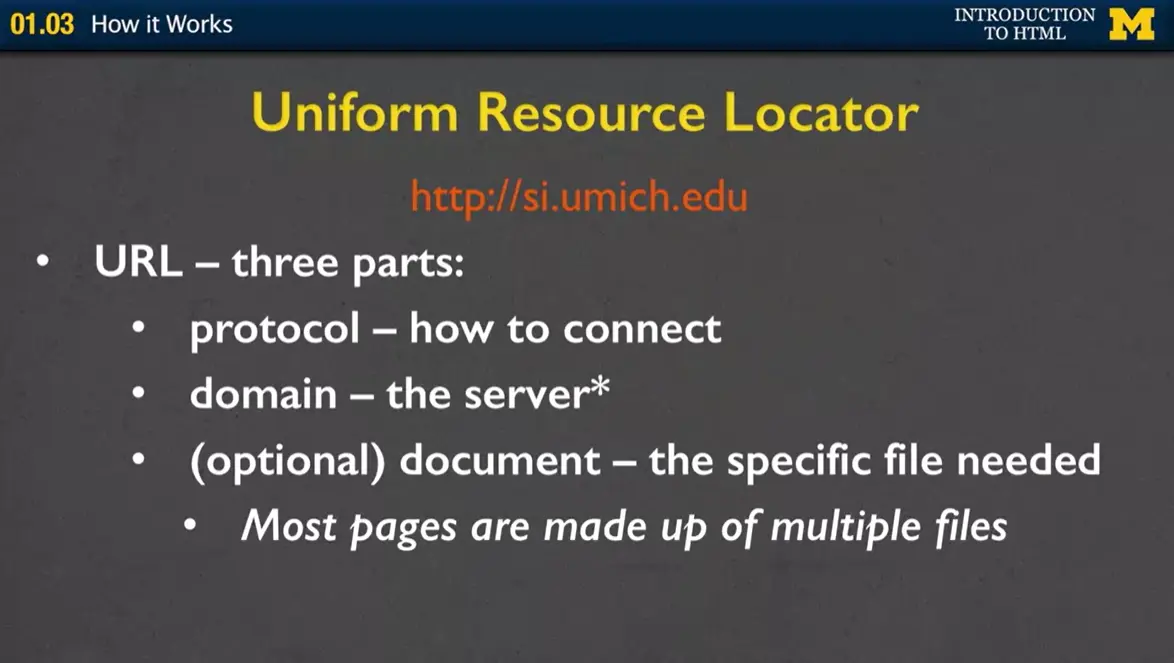

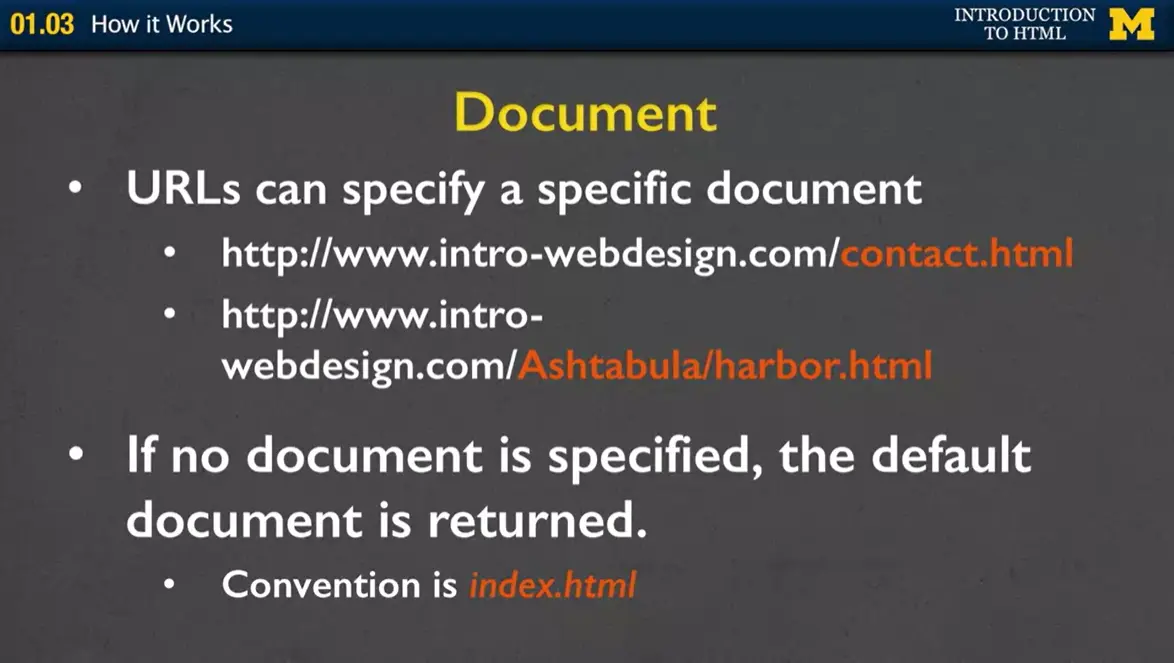

When you type something in, this is called the URL. Every URL has three parts. The protocol, how you want to connect, the domain, which is the server, and then optionally, you can include the document. So, even though you're typing in one URL, one of the things to realize is that usually, you're actually requesting lots and lots of files all at once.

The protocols that most people have seen; the first one is HTTP, the Hypertext Transfer Protocol. The second one, HTTPS, is the same idea, only now we're having a more secure protocol. So, if you're ever connecting to a bank or any place where you're putting in passwords, make sure that the first thing you see in that URL is HTTPS. If you don't, don't connect.

The third one is called the File Transfer Protocol. It's a little bit different. When you see HTTP, it's expecting that you're going to give back and forth HTML5 code; with FTP, it could be any type of file.

We have the protocol, now let's talk about what the domain names represent. Usually, the domain names are something recognizable, such as umich.edu, would be for University of Michigan. Google.com, wikipedia.org. So, each of these sites has a different top-level domain. How did you get them? How do some people get to be .edu and some .com, some .biz, et cetera? Well, they're actually determined by ICAAN. Their job is to go in and decide which types of organizations qualify for different domains. I've included a link here if you want, you can go and see what the different types are.

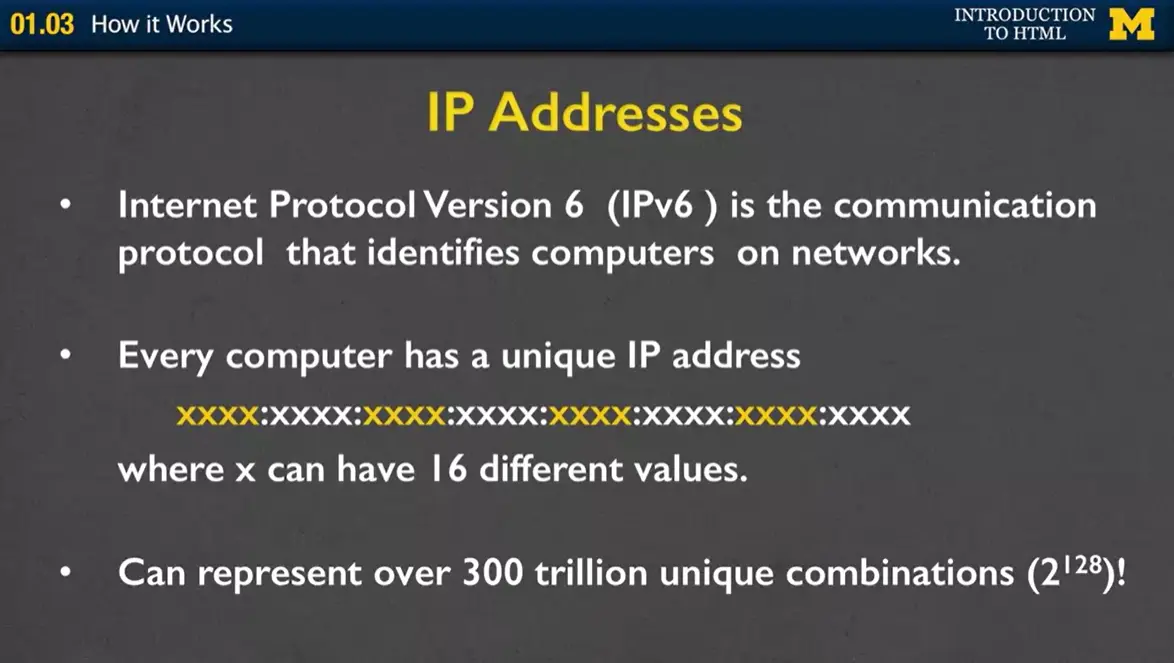

But the important thing to know is that your domain name is actually mapped to an address. In the old days, like when my Dad was on the Internet, if he wanted to connect to some place, he would actually type in numbers; 185.261 et cetera, et cetera. Well, there's been a new version of IP addresses, because every single client needs their own address. If you think of how many people have laptops and smartphones, we need a lot of different options.

With these IP addresses, you basically have sets of numbers, you have these different sets right here, where each X can represent one of 16 different values. So, you can see we have a lot of options, over 300 trillion, in fact.

As I said, luckily for you, the domain name server lets you type in something really simple like Umich or Google, and it's the one that turns it into that really long number.

The last part of your URL is the document. Sometimes you want to specify a very specific document that you want to get. For instance, the contact page, or in this case, another one I have the file that's inside a folder. But sometimes you don't put a document at all. In fact, most of the time, you don't. If you type in wikipedia.org or Facebook.com, there's no filename. But that's okay. Every server has a default document that it's going to return. Usually, it's called index.html.

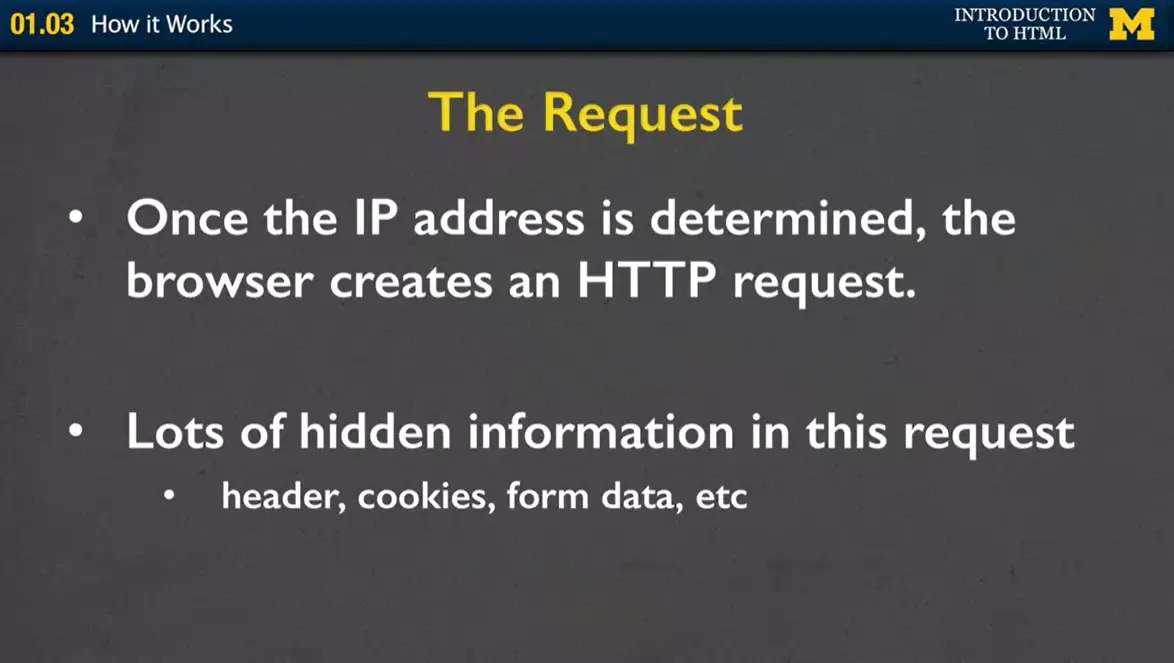

We know what it means when we're typing something in. We understand the request. What happens though once we type that in, is we are actually going to get back a lot of information. Headers, cookies, form data, all the stuff that you don't see.

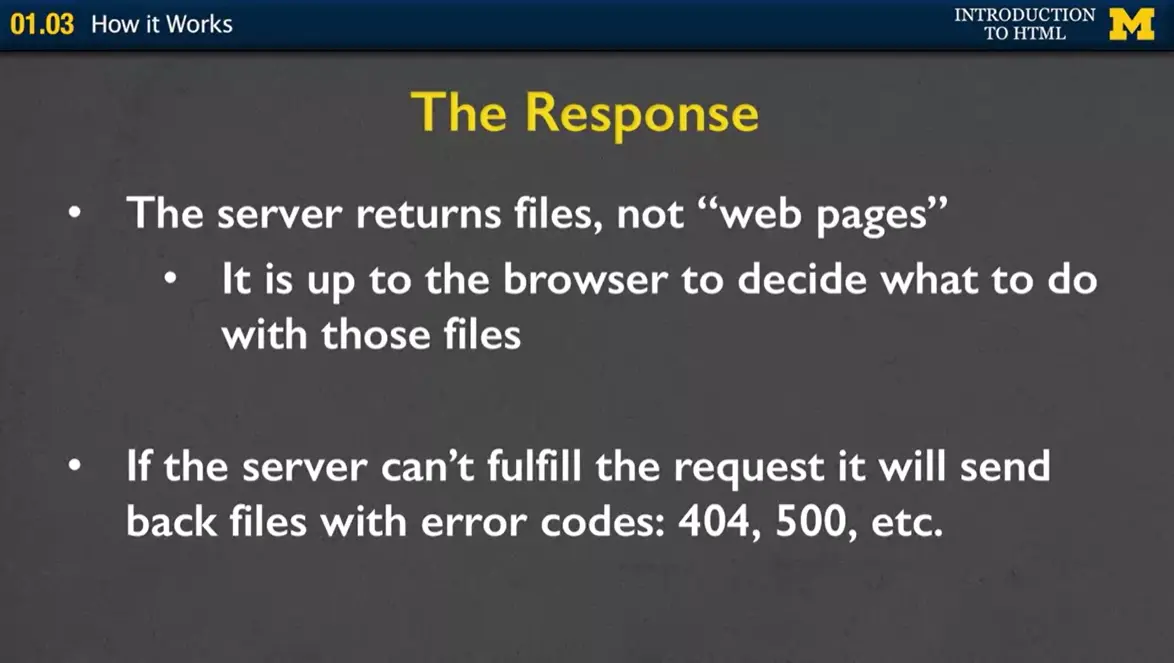

The important thing to know is that the server returns files, not web pages. For a lot of us, we are very visual. So, when we type in a URL, we're looking and we're like, "Oh, here's my page." But sometimes the browser might be returning something for different types of screen readers, assistive technology, so it's not returning a web page, it's returning lots and lots of files. Hopefully. I will admit that sometimes the server can't fulfill the request. If it can't, it'll send back an error code. I think a lot of you are familiar with 404, where it says, "File not found." That usually means you typed something in wrong. If you get a 500 error, that actually means that the servers down. So, you may as well go have a snack, do something fun, come back later and type it in again.

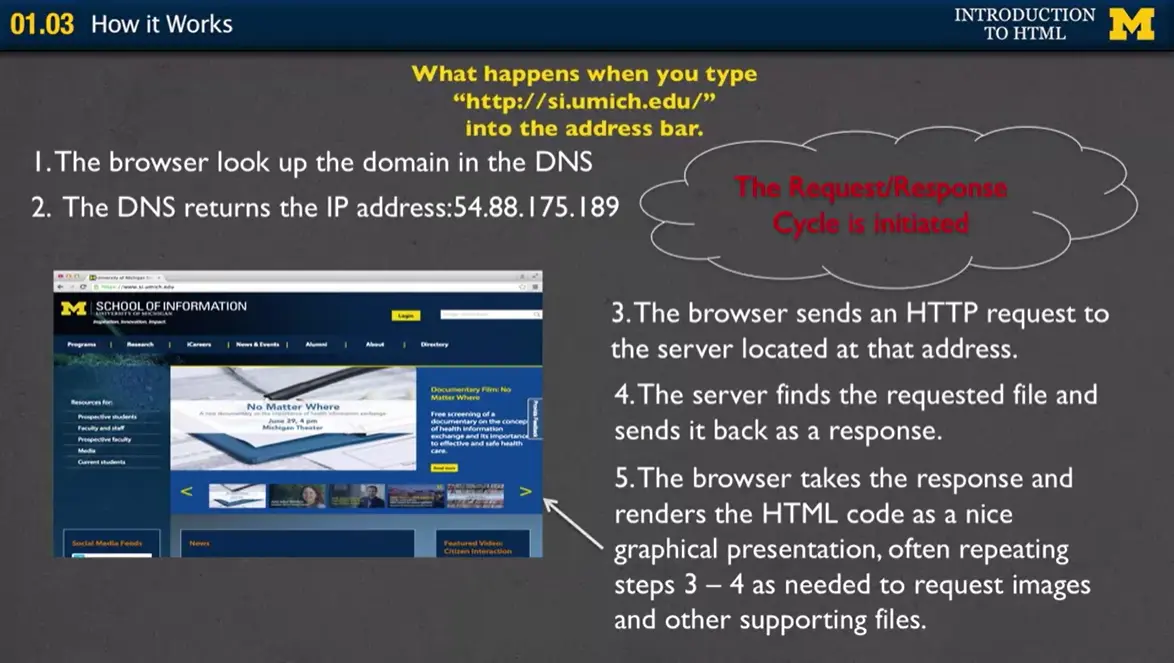

I want to kind of do a live demo with you of what happens when we type something in. I've written it down for you. It looks up the domain, the DNS returns an IP address, and then a whole bunch of files start to be returned. Let's take a look.

What I've done here is I've gone to the School of Information site at the University of Michigan. I simply typed in si.umich.edu. I didn't type in the protocol because it usually just defaults. What you see here visually is a page. Student looking out, looking very inspired, et cetera.

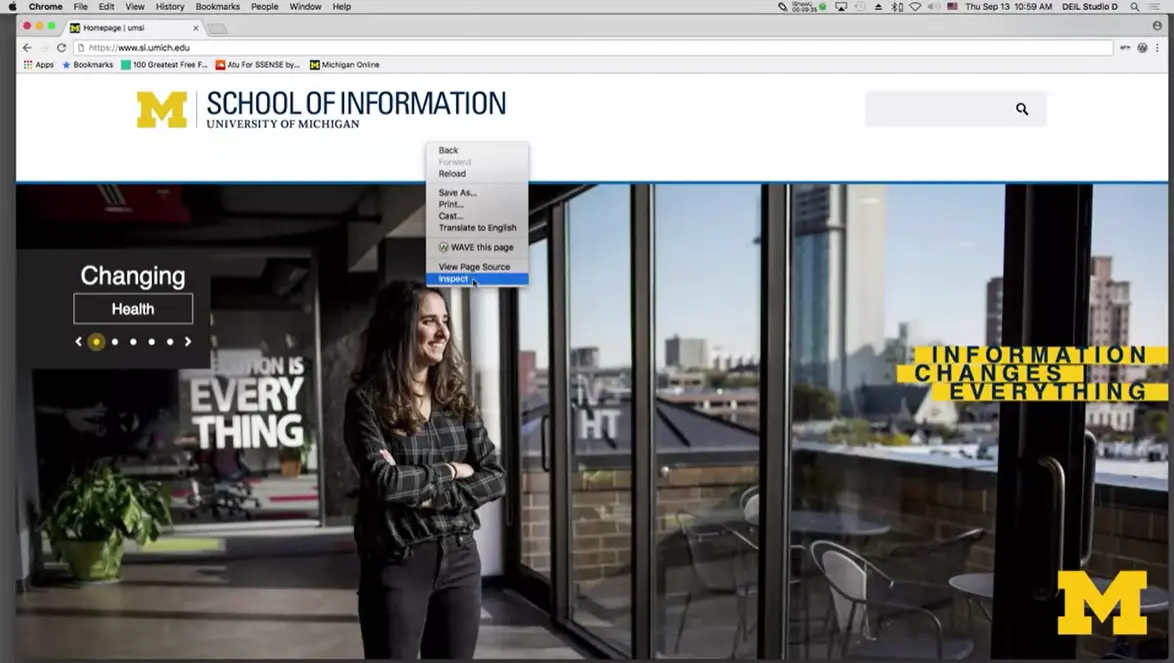

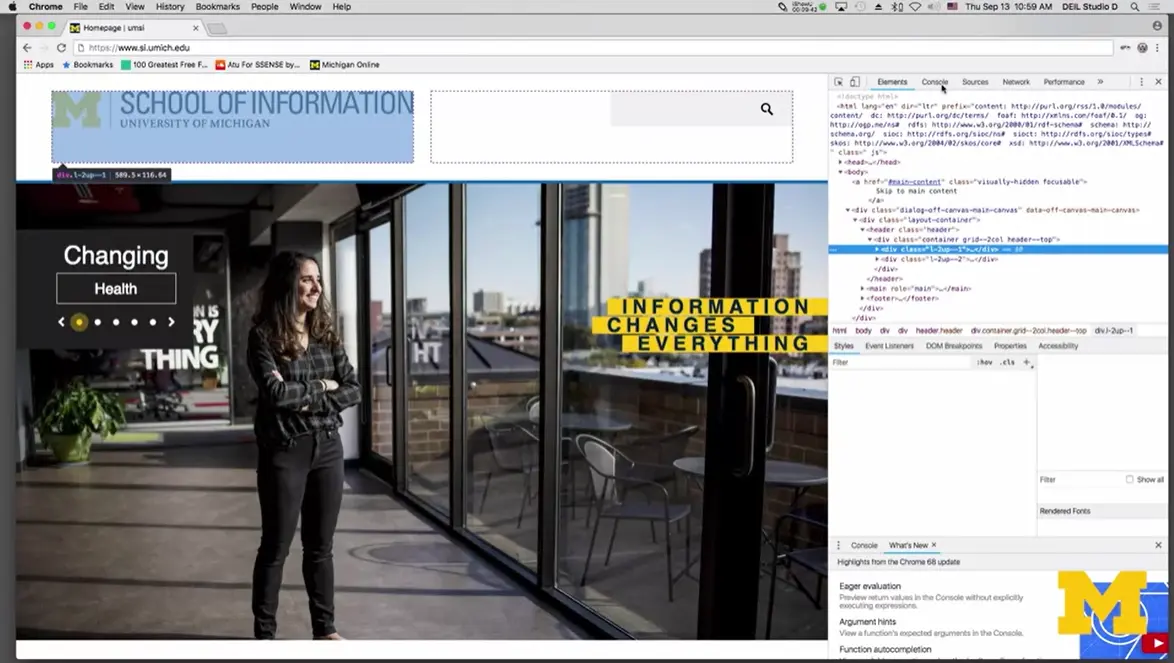

But now, I'm going to do a little trick here, where I right-click on the screen, and I'm going to choose the option that says, "Inspect." A window's going to pop up to the side here. I'm going to say, "You know what? I would like to see all the information that's being returned when I actually request this page."

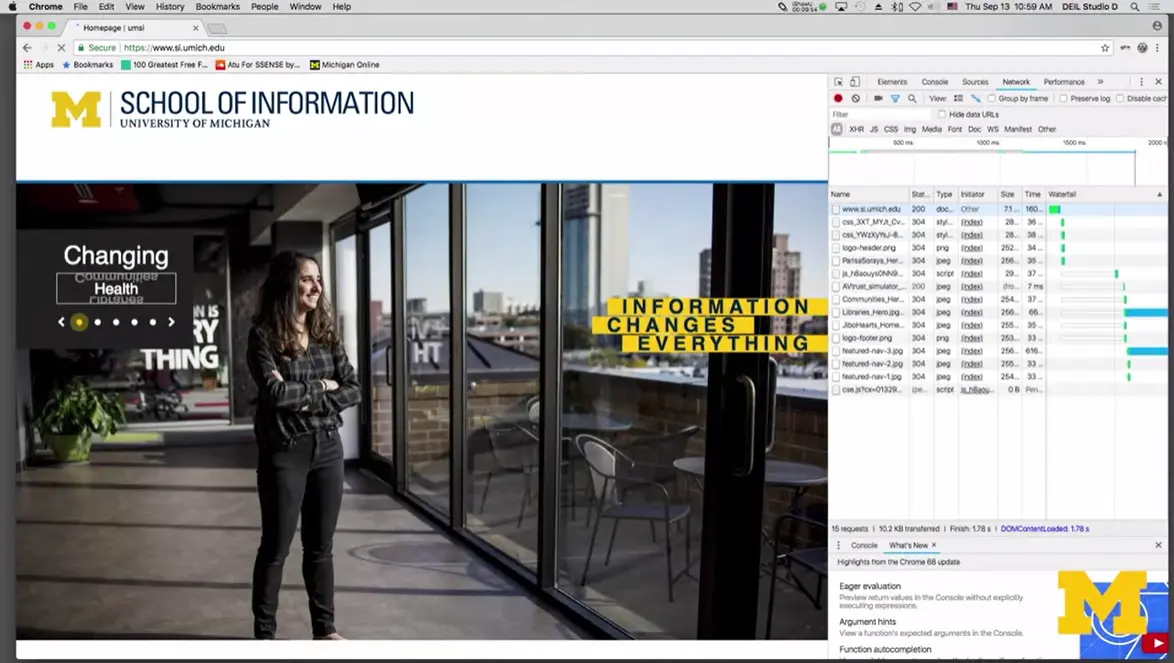

I'm requesting one page, I'm going to hit "Refresh." If you look off to the side, don't worry that you can't see the details. But you should see that the single page is actually made up of lots and lots of files, and each one of these files was a separate request.

Okay. So, let's review. This was a kind of long video, where really all I want you to come away from it with is the knowledge that every URL has those three parts; the protocol, the domain, and the document. And, realize that what you're creating is bigger than just one file at a time. Every request-response cycle is usually lots and lots of rounds of communication between the client and the server. So, we're going to start off small. We're going to do one file at a time, but you can always look ahead to building bigger and bigger web applications.

Browsers are constantly changing. Changing so much that it is difficult to keep up with all of the changes once you pick a favorite. Myself? I got a Mac a few years ago and have been using Chrome. But oftentimes I switch to Firefox because it allows me to run some programs that Chrome has trouble with. So please remember that many times a page that looks a certain way in one browser will look different in another. I highly recommend that you check your page on two different browsers if you ever get stuck on a site.

In the lecture video I will do my best to touch on some of the most popular browsers. But I am including here a link to an optional reading on the "best" browsers. This is an optional reading because I don't like the popups that accompany it.

Some people are very loyal to their browsers, any of my comments here are just my views! I hope that we have taken some of the mystery away from how browsers work and why there are so many.

One of the things that you might notice is that there are a lot of different options for how you can view web pages, and these different options are called your different browsers.

Different browsers have their pros and cons. I am not one of those people who gets really passionate about having, using one over the other. But I will tell you, as you become a web developer, if you decide to, you're going to want to know some of these differences. It's perfectly natural to have a preferred browser, for most people it's whichever one was installed on their computer. But, when you want to create websites, you might have one browser you use to look at things, but you really want to test your site on multiple browsers.

So, let's talk about some of the differences. First, we have Internet Explorer and for a long time, it was the most popular browser and that was just because it was the one that came with Microsoft Windows. It was, and always has been the worst of all browsers. A true piece of shit.

It was platform-dependent and what that means is that it doesn't automatically work if you have a Mac.

In 2015 Windows 10 came out and instead of including Internet Explorer as a default, it's using something called the Microsoft Edge. An even worse browser. Edge is meant to replace Internet Explorer. So people who buy new computers are going to be using Edge. But don't forget people don't buy new computers all the time or even if they do buy a new computer, they might decide they still like Internet Explorer better. So you basically want to make sure that you're considering both browsers.

Another option is Google Chrome. Google Chrome was developed by, surprise, Google, and it was a freeware that they created to be used on Microsoft Windows. However, it was later re-written so it works on Linux, Apple, Android, and most machines that you're going to come across. The nice thing about Google Chrome is that they really focused on security. Unlike Microsoft, they care more. Unlike Microsoft, they get hacked one hell of a lot less. And this is partially why. Not so lazy as Microsoft. If that’s something that you’re concerned about, Chrome is a good way to go.

The next option is Firefox. Once again, the theme seems to be, I’m always recommending free and open source browsers. What open source means is that they've actually shared their code with everyone (unlike Microsoft) for how they created Firefox. And this is a great way to let people make suggestions and improvements to it. It's also available for Windows, macOS, Linux, and different BSD operating systems.

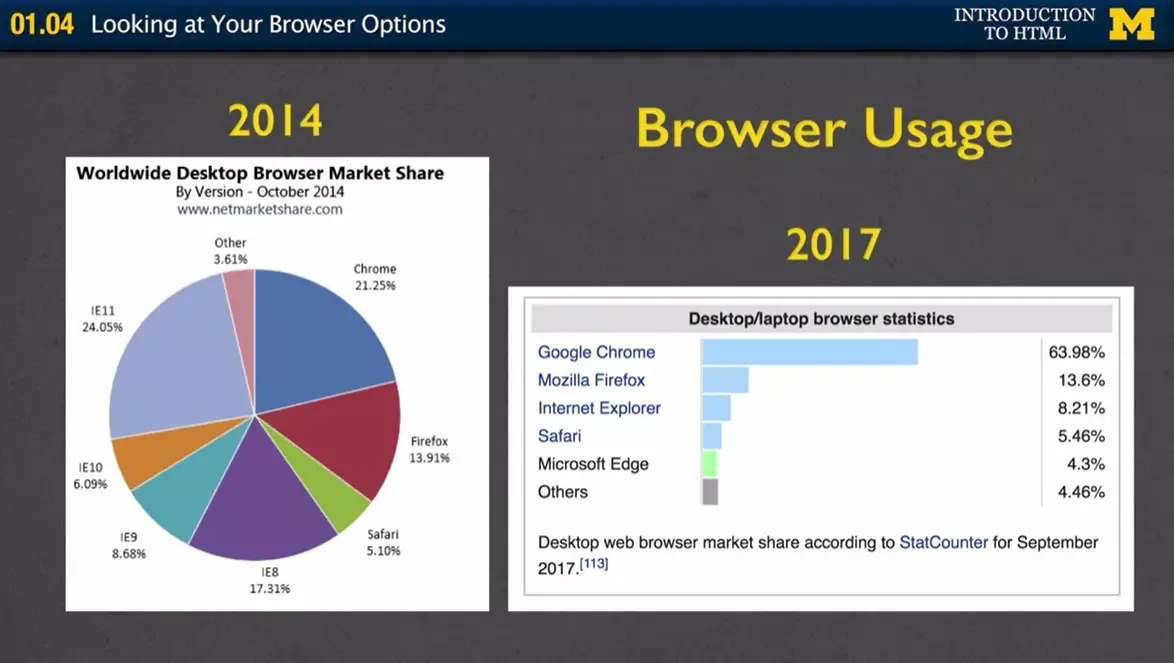

So who's using the different browsers? Back in 2014, I can show you that Internet Explorer had a really big chunk of the market, right around there. You had Internet Explorer 11, Internet Explorer 10, Internet Explorer 9 etc. All pieces of shit. They had the biggest chunk and then Chrome was getting a lot bigger as well as Firefox. Well, when we look over here at 2017 though, we can see that Chrome really made a big surge and up to 64% of desktops and laptops were using Google Chrome, followed by Firefox, Internet Explorer etc. This is always going to change, it's going to flux. You can't pick one browser and say hey, this is the new one that's everyone is going to be using. And the other interesting thing to kind of think about is, especially in this old map over here, people use really old browsers because people like to use what they're used to.

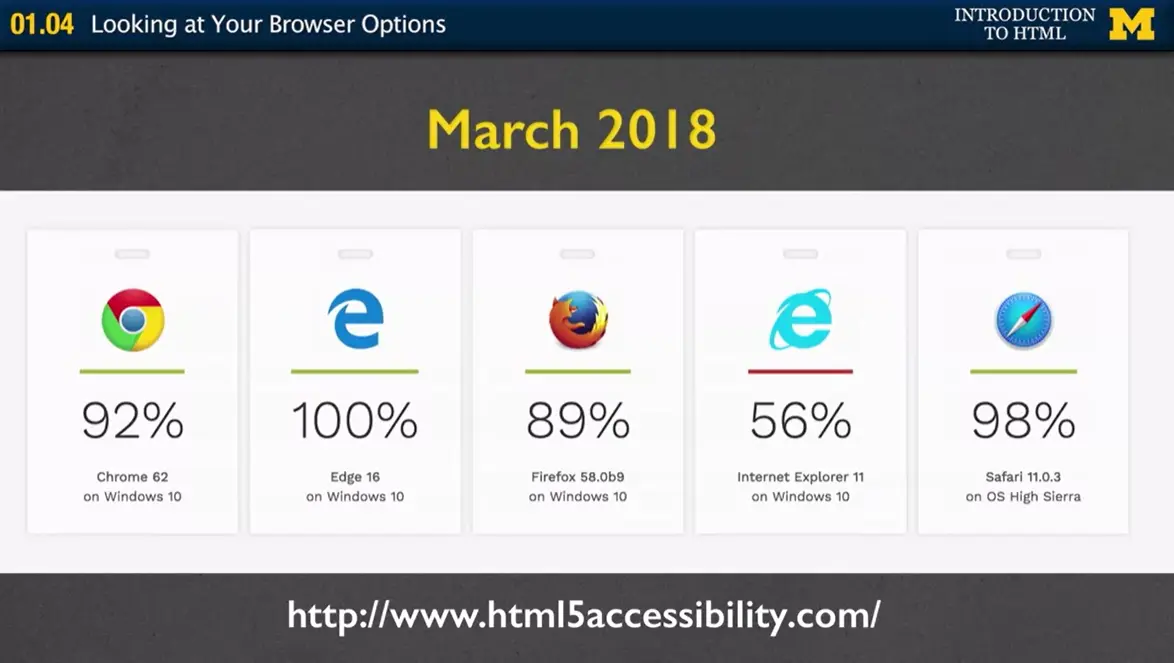

One thing that I'm hoping all the students in my class take into consideration though, is accessibility. Accessibility is basically the ability of a browser to support all these special functionalities, and all these new HTML5 tags, and all types of assistive technology.

One place you can go is this site www.html5accessibility.com. And what you'll find at this site is how well the different browsers are supporting the text. So you can see right now, Edge actually has 100% compliance which isn't surprising because it's one of the newest browsers, so they had accesibility in mind right from the beginning. The other browsers were created before people were paying quite as much attention, so they are definitely making strides to get better and better. However, it is important to notice that Internet Explorer is at 56% and since it's been basically relegated into the background, it's unlikely that it's going to get much better. Greed and arrogance kept Microsoft behind.

So what I want you to take away from this is that browsers can vary in how well they adhere to different standards. And different versions of browsers also need to be considered as well. Just because something didn't work in 2018, doesn't mean it won't work in 2019. So the best thing that you can do is write your code, and then open it up in Safari, and Firefox, and Chrome, as many different browsers as you can. Just not IE unless you have a shit load of extra time to re-write everything. Not only will it make your site better, but it will be a little bit interesting for you as you can look at the different ways that HTML5 is supported.

One of the things that you're going to learn about making your web pages

is that once in a while, you have to bite the bullet and stop listening

to me and start creating things on your own. Until now, we've talked

about browsers and how you can look at webpages but when it comes time

to create a webpage, we have to use a different type of software called

an editor. Before we begin typing in your code though, it is always

worth your time to organize yourself and organize your files.

One of the things that you're going to learn about making your web pages

is that once in a while, you have to bite the bullet and stop listening

to me and start creating things on your own. Until now, we've talked

about browsers and how you can look at webpages but when it comes time

to create a webpage, we have to use a different type of software called

an editor. Before we begin typing in your code though, it is always

worth your time to organize yourself and organize your files.

Step 1, you need to decide where on your computer you're going to save your HTML files. I highly recommend that you make your own folder called HTML, maybe HTML week 1, week 2, but something so that you can find your code.

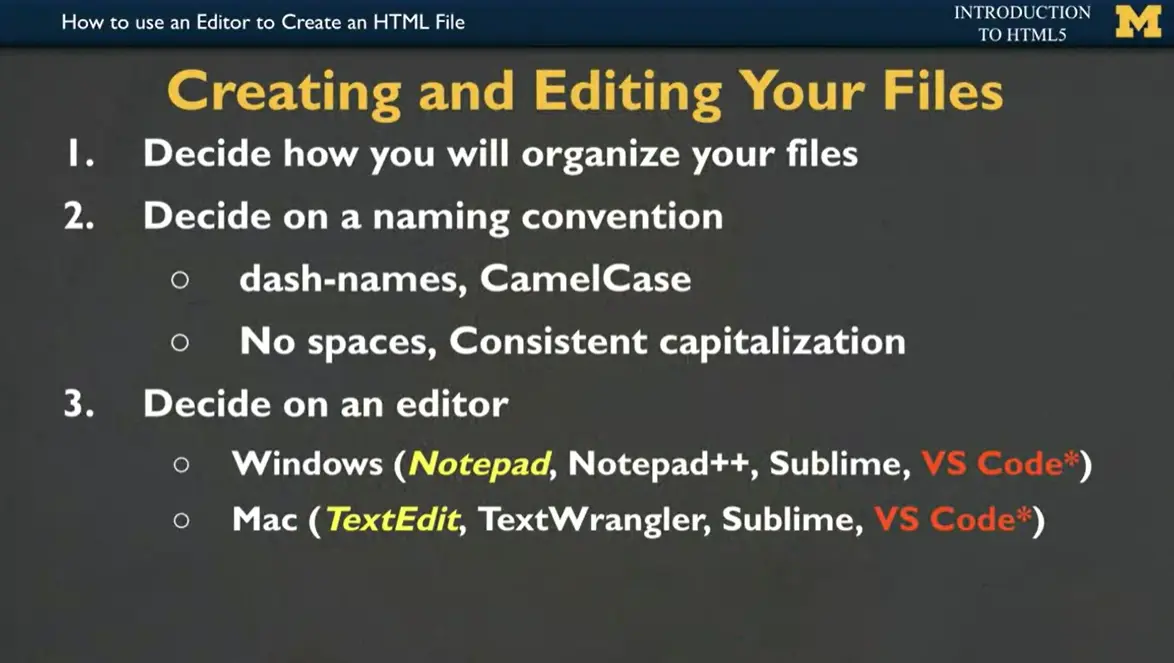

Step 2, you need to come up with a naming convention. This is a fancy way of saying name your file something that you're going to remember. Usually in class I end up with like 18 different files that all say page 1, page 2, page 3, and that's not really helpful for me figuring out what's inside the page. So when you come up with your names, it's usually a good idea to have two-word names such as your Intro Page, Favorite Restaurants, Summer Pictures. When you use two names though, you can't leave spaces between the names, so you'll often add a dash between it or use something called camelCase, where you use lowercase for the first word and uppercase for the second name to have that little hump as if you're a camel. But again, it's very important that you do not use spaces and that you're very consistent with your capitalization. Computers don't like it when you aren't consistent.

Step 3, you need to do is decide on an editor. If you're using Windows, you might be tempted to use Notepad because it's a built in editor that you can find easily. But it wasn’t conducive to creating webpages. Instead, I would recommend Notepad++, Sublime or VS Code, also called Visual Studio Code. In the same way, on a Mac, you can always find a software editor called TextEdit. But again, it doesn't have the cool tips and tricks that you can use to make a webpage, so instead, I would recommend TextWrangler, Sublime, or again, VS Code. All of these editors are free, but some of them, you might have to take that extra step to download and put on your computer.

If you're a paid learner on the Coursera platform, you do have access to VS Code right here within the site. But if you're one of our non-paid learners, don't worry, you can still do everything we do. You just have to download it first.

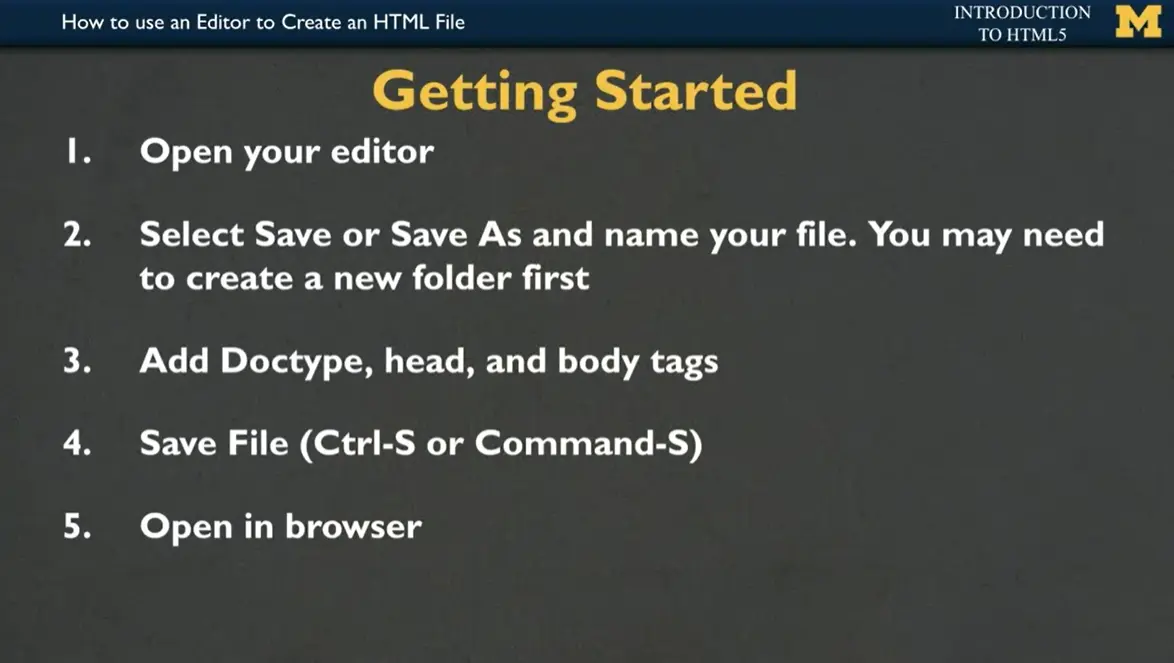

Once you've decided on your editor, you're going to open it up and then I'm going to want you to save your file and when you go to save it, don't forget to put it in a nicely named folder so you can find it later.

The next step is to add three parts to a page. The Doctype, which says, hey, I'm going to use HTML5. The head section of your page, which is usually where you put your title so people can see it on the top and then any tags or content you want in the body. Save often, every time you type in a few lines, hit that Control-S or Command-S. It's a shortcut for saving your file. Then when you're all done, you have your code in your editor but you want to open up your page in your browser so you can see all the cool stuff that you've made.

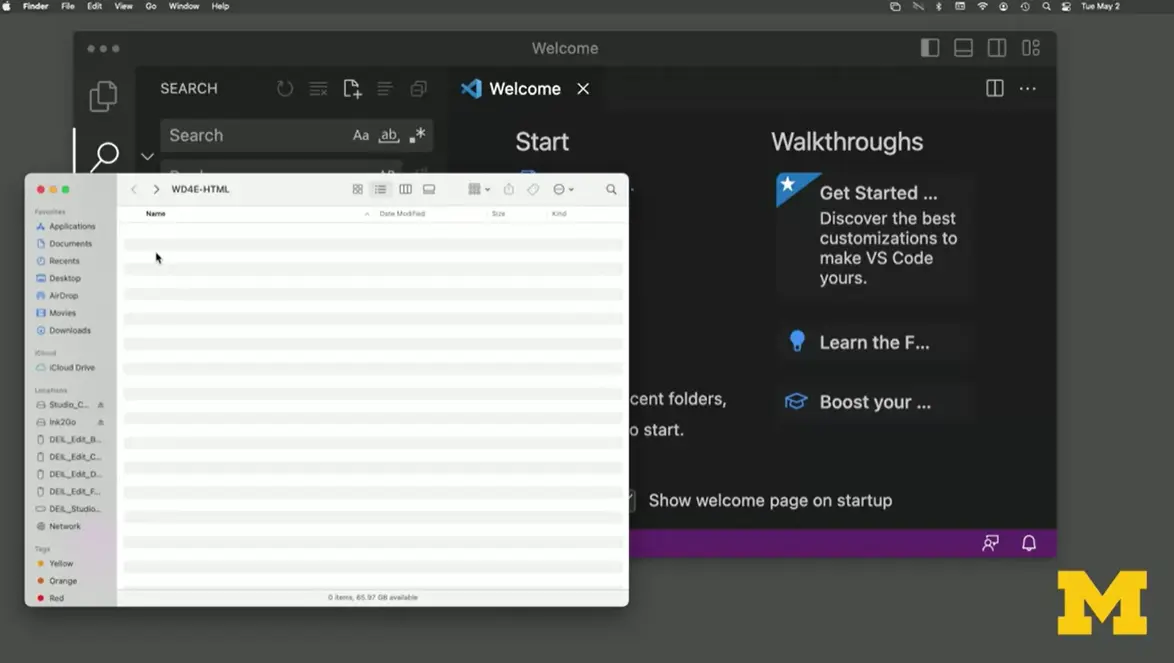

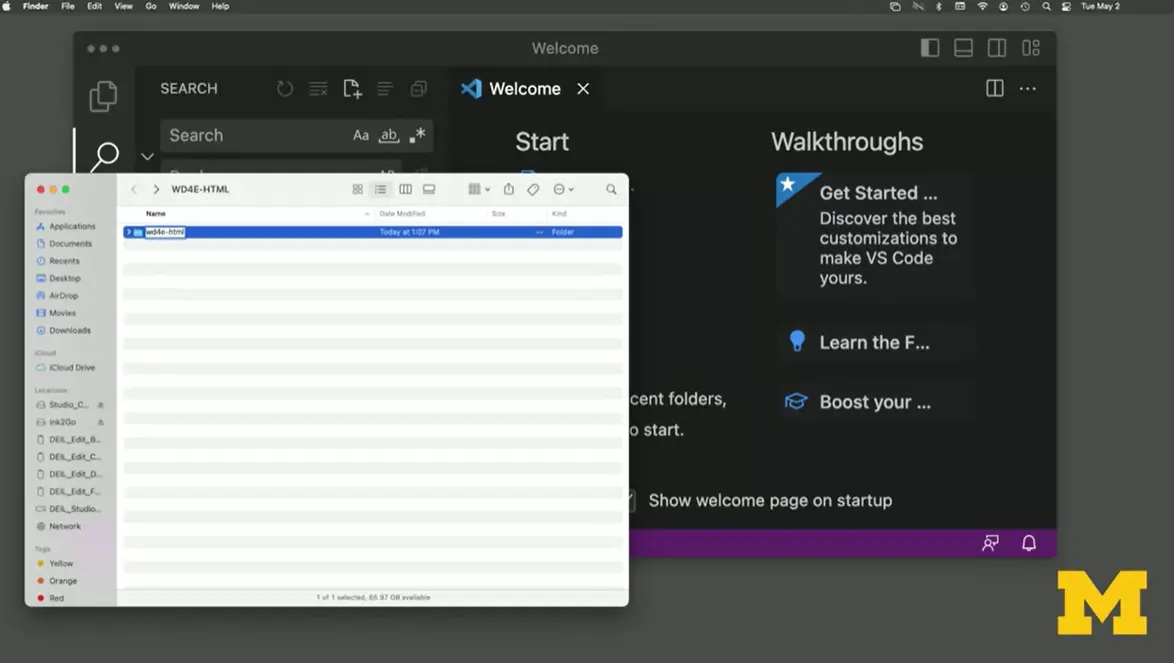

Let's try this together using Visual Studio Code. The first thing that I'm going to do is make a folder called "WD4E." I'm going to right- click and click on "New Folder" or you can also go to "File," "New Folder," and I'm going to name it as I mentioned, just something I'll remember, WD4E, and maybe add an HTML because we're going to do a lot of coding together. So now I have my folder where I want to keep my files. I've opened up Visual Studio Code and don't be scared off by all these different options. Focus in on the one option that says "New File" and we want to use a regular old text file.

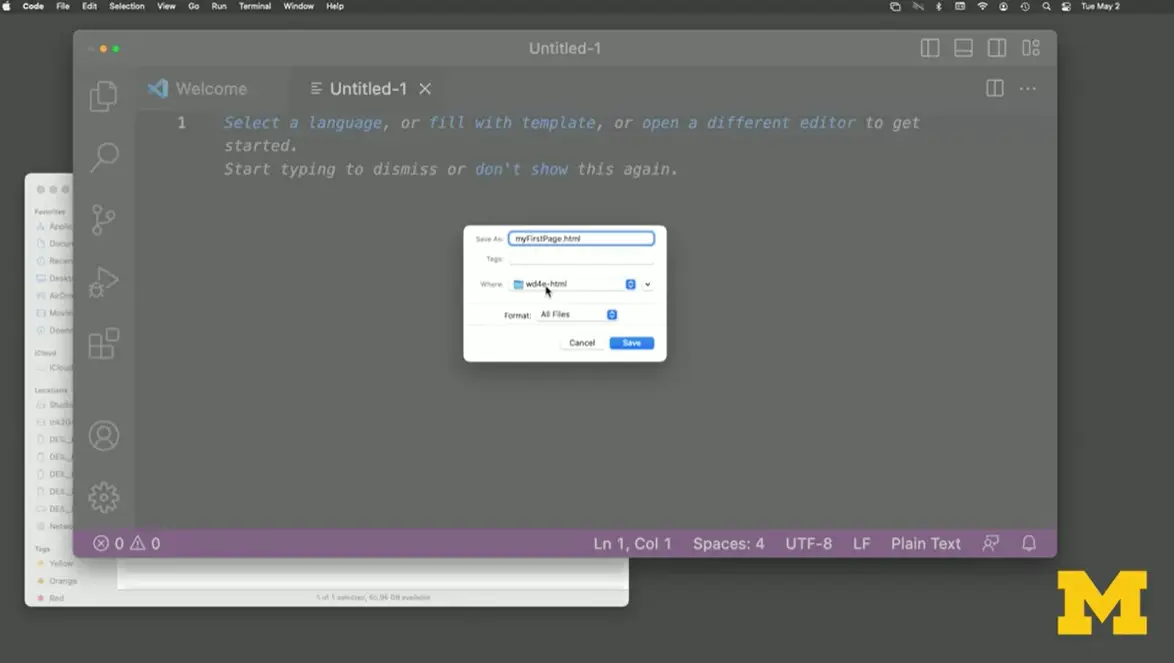

I'm going to close this window over here and remember I said one of the first things we want to do is we want to save this file, so for the first time, I welcome you to go to "File" and then "Save As." I'm going to call this, myFirstPage.html. If you notice, it has in my WD4E folder, that's very important. We want to make sure it's in there. I'm going to hit ''Save.''

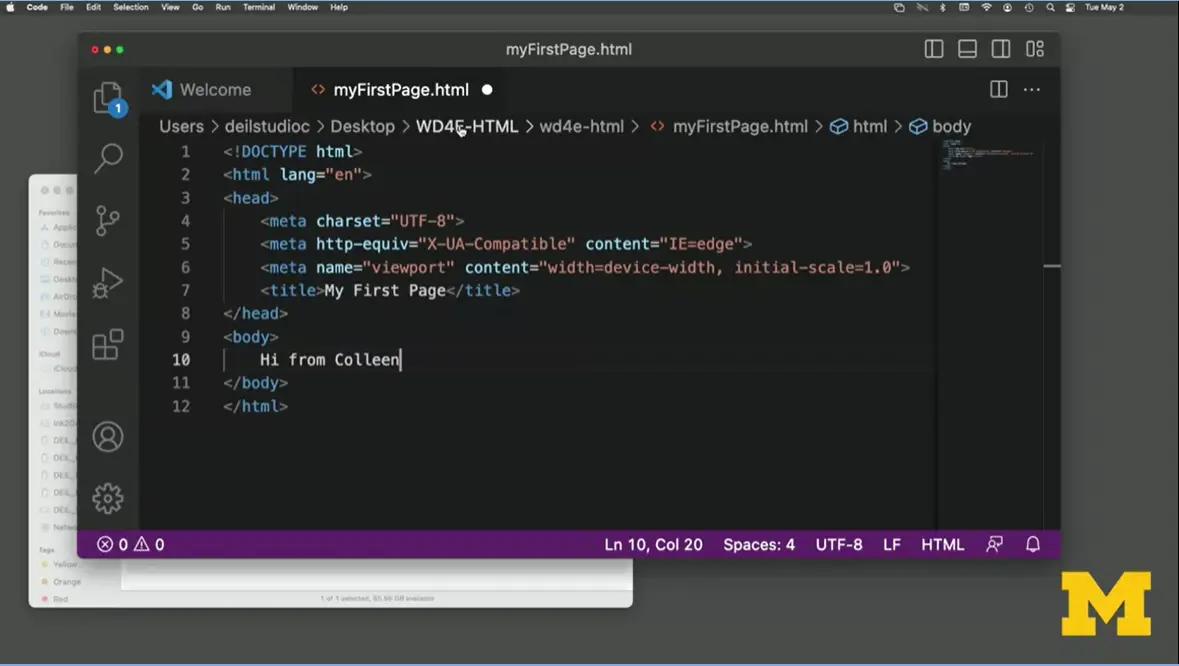

Our next step is very tricky and exciting and makes you feel like a real coder, even though we haven't done any coding before. Because I told Visual Studio Code that this is an HTML file, do you see up there? I am able to do exclamation point, Tab. It fills in all this crazy HTML stuff that we might not know how to use. The important part to notice is that I've included DOCTYPE html. There's a title in here. I think I'll change this title to, "My First Page." There's a body tag where I'm just going to say, "Hi from Colleen." If I look up here near the top, I can see there's a little circle next to my file name. If you see a circle, that means I haven't saved it recently. I am going to do a Command-S to save it. Now I've made my first page. Yay!

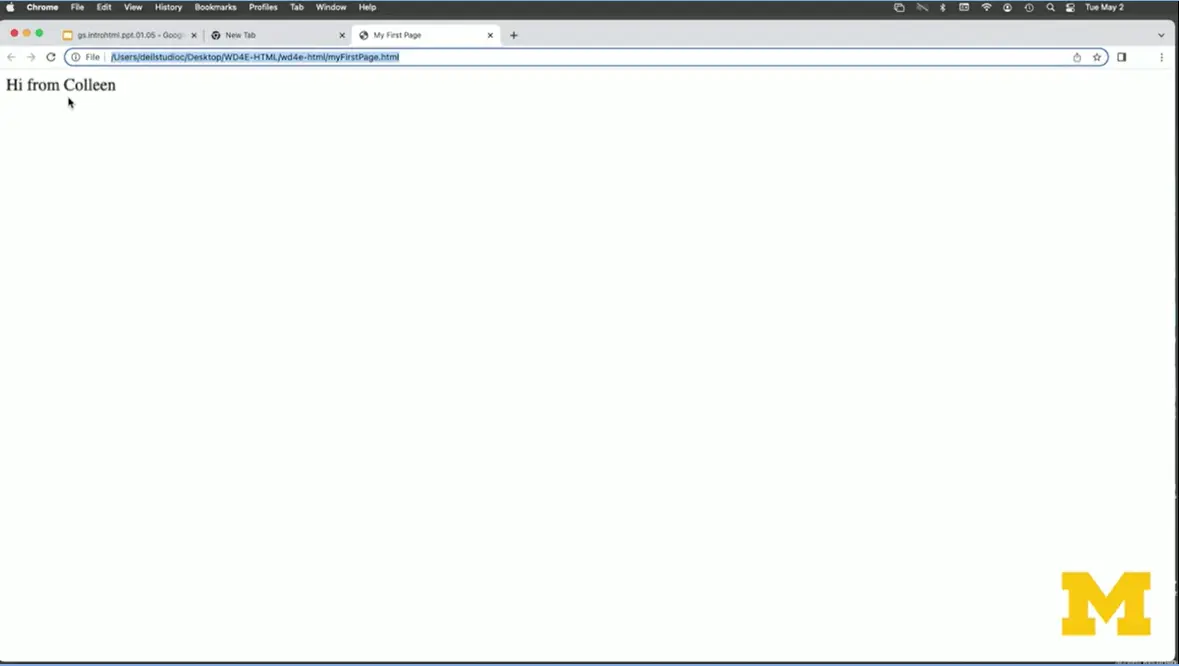

But I need that last step (#5). That last step is how do you go from looking at something as an editor to actually seeing it in your browser. And that's where it's so important to make sure that you remember where you saved your file. I'm going to open up my folder, make this a little bigger for you. I'm going to click on "myFirstPage.html". As you can see, I get the, Oh, so exciting page that says "Hi from Colleen."

One of the reasons a lot of people give up on coding early on is that there's actually a lot of ways and places that things can go wrong. Let's learn how to go on and search for things. But I would really like to try to prepare you to know, there are some things that you're going to do and everyone does it, so it's okay.

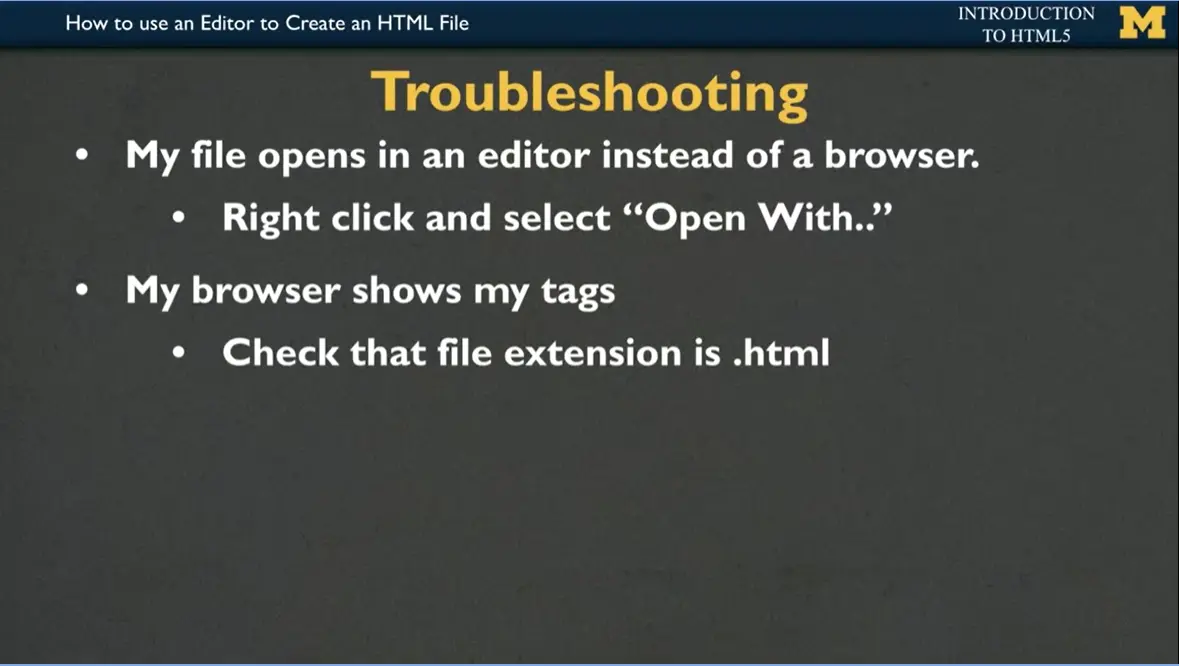

The first thing that happens to many people is that when they click on their file, instead of opening up in Chrome or Safari, or Firefox, it opens back up in Sublime or TextEdit. It opens up in the editor. If that happens to you, you're going to want to right-click on your file and select ''Open With,'' and then you can pick up a browser.

Sometimes when you open your page, instead of seeing the content that you are hoping,

you actually see all that ugly HTML code and you can't figure out why

it's showing you that text rather than the pretty page. If that's the

case, usually the problem is that your file extension, you forgot to

save it as .html. You're going to want to go back and check that.

Another problem that can happen is you can change your code. But even after you've changed it, so that instead of saying, "Hi from Colleen," maybe you want to say, "Hi from Catherine," "Hi from Sochi." You change it and nothing happens. Just because you change your HTML file in your editor and you've saved it, you still need to go in and tell your browser, Hey, I have a new version and that's called refreshing your browser. You can either go back up to the top and hit the "Refresh" button, or you can try to use something called a shortcut, which is to just type in Command or Control-R.

Also, don't forget to verify your file name. Sometimes we think we're opening one file, but we're actually opening a different one. Another problem that people often get is they get what we call like weird characters. Things that don't look like English. That happens most often when people copy and paste code from a PowerPoint or Google Slide, instead of typing them by hand. They pick up these hidden characters. Try those things if it's not working for you, try refreshing the page, try going back, and making sure you saved your file. And if you copied and pasted, try to go back in and type it in by hand.

Throughout the rest of this course, you will see examples that I have written in TextEdit, in Sublime, in VS Code, and something new for the latest version of this class is something called Replit. TextEdit, as I mentioned, is built in. Sometimes people like to use that. But it really leads to a lot of problems that first-time coders just shouldn't be bothering with. Sublime is a free option for editors where you can download it and it'll give you lots of nice tips and tools very similar to VS Code.

Replit, however, is going to be something that I encourage all of you to use. Because Replit not only let you edit your code it's also going to let you share your code with your friends and family all across the country and all across the world. But wherever you feel most comfortable, pick one, maybe two editors. And that's what you're going to want to focus on and really become a pro.

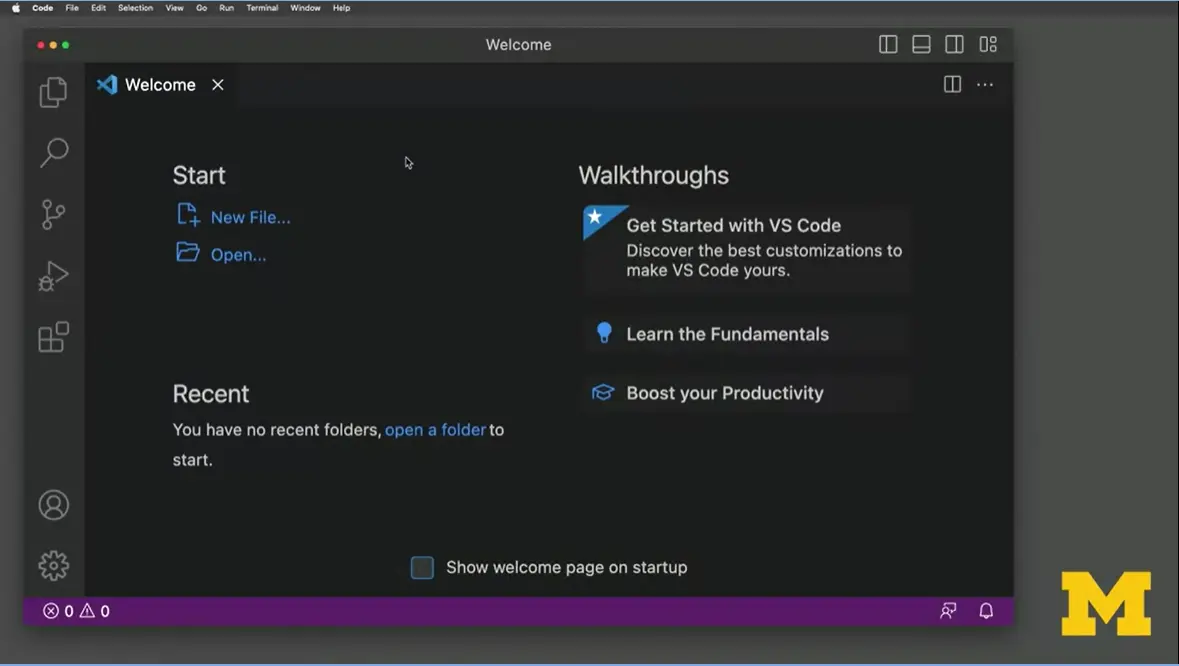

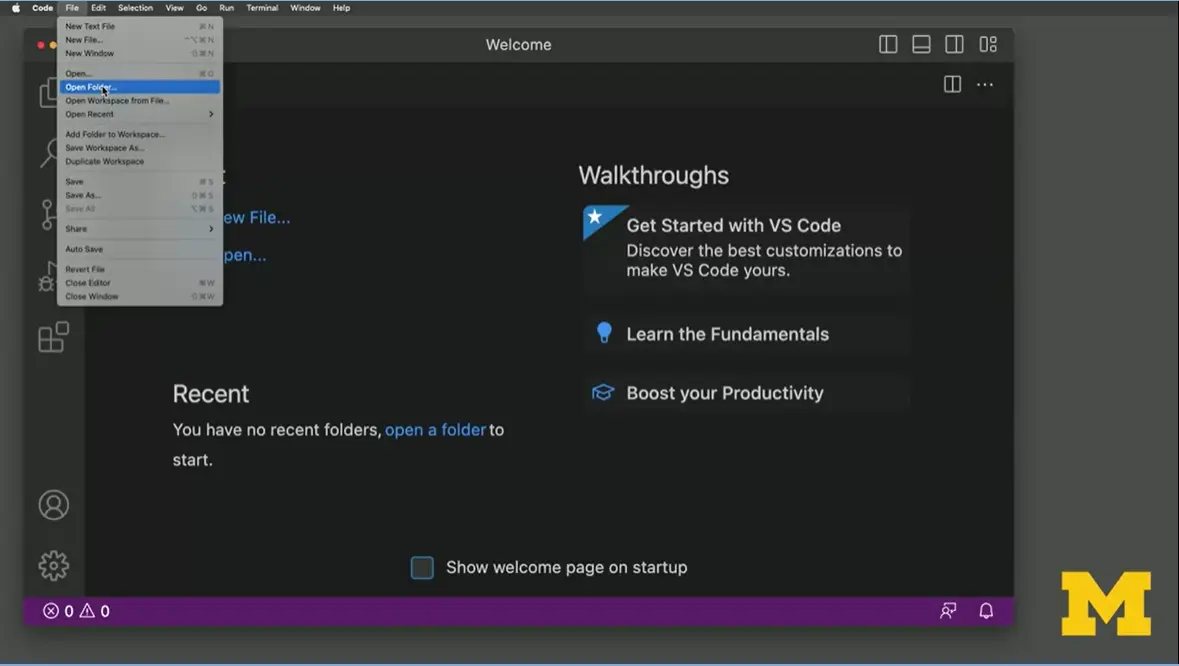

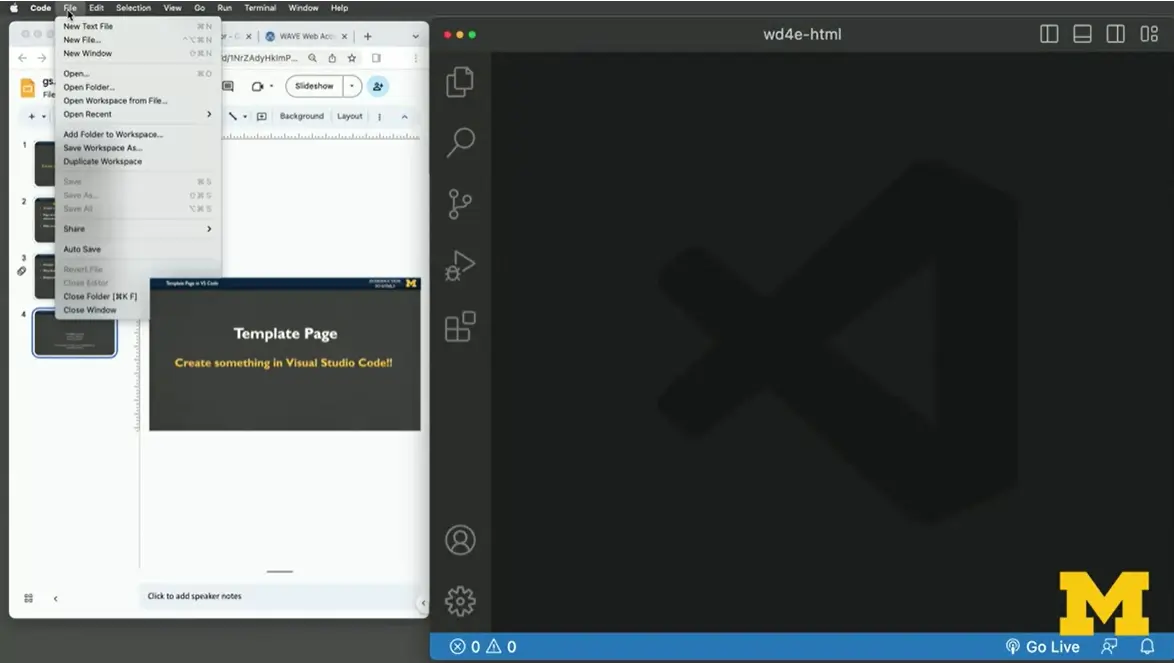

Let's talk about how to use Visual Studio code.

Once you open up Visual Studio Code, it's not unusual to be overwhelmed at first as to what you should be doing. Particularly since when we think of webpages, we like to think of a web page is being one-page. But actually a web page is numerous files that are all put together.

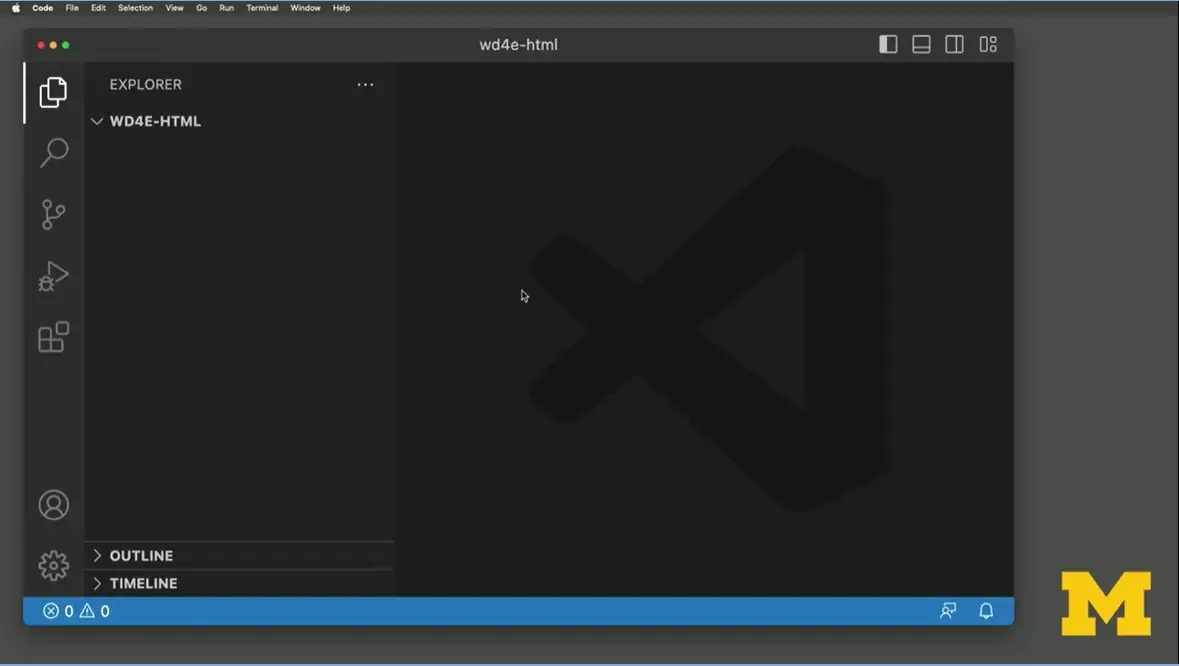

My recommendation for you is once you start Visual Studio Code to always click on "File," "Open Folder," and navigate to the folder that you created for your site. In this case, it's "wd4e-html."

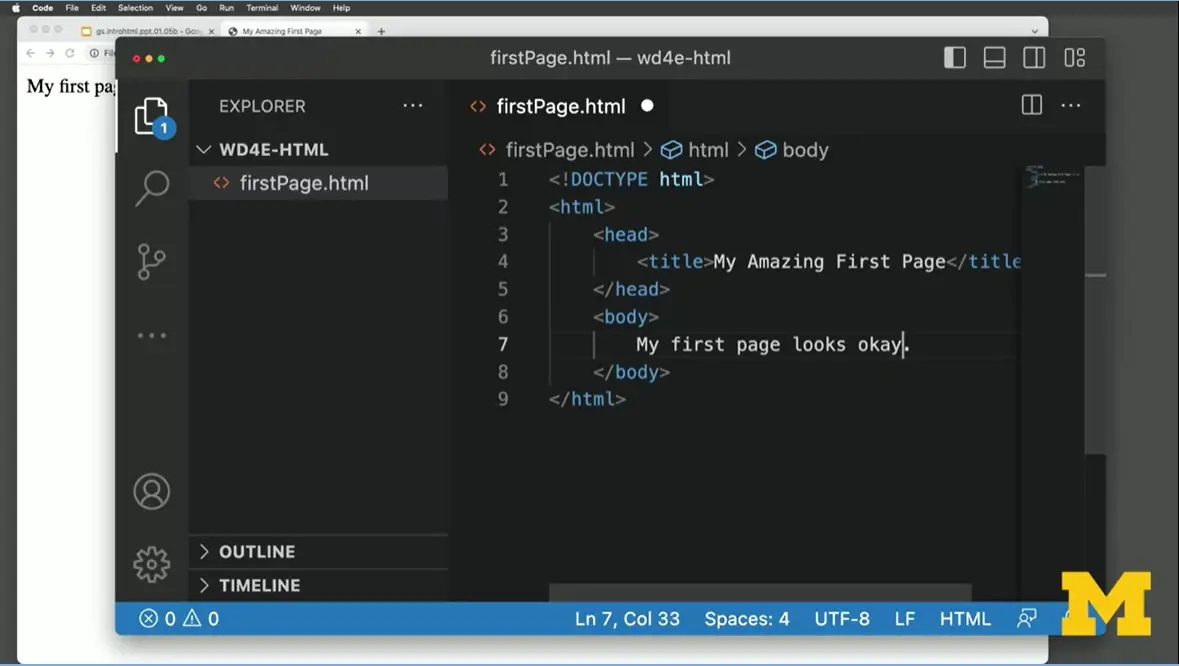

The reason that you want to open an entire folder, and I'm going to say, yes, I trust the authors because it's me, is because off here to the left, there is something called the Explorer that will list all the different files you have, which right now isn't that many. But when you create sites that include images or CSS, or even a site that has three or four pages, having this outline is going to let you link them together. Let's start off by making a simple file. I'm going to do new text file. I won't do anything fancy this time. I'm just going to do a command-S and I'm going to call this "firstPage.html." I'm going to add some of the code that we talked about when we make a page which is DOCTYPE.

I'm going to stop for just a second, and point out that Visual Studio Code has already figured out what I'm trying to type in. They even realize that I have a typo and that I forgot that first initial exclamation point. I'm going to hit "Tab" and it finishes the DOCTYPE for me. I'm going to add my HTML tag and as I finished, it added the closing tag. I'm going to add my head. I'm going to add a title. Let's call it, "My Amazing First Page." You know what, did you notice I'm running out of space. Let's resize this a little bit, so we can have as much room as we want. My First Page. Then I'm going to add a body tag, where I will again just say, "My first page looks great."

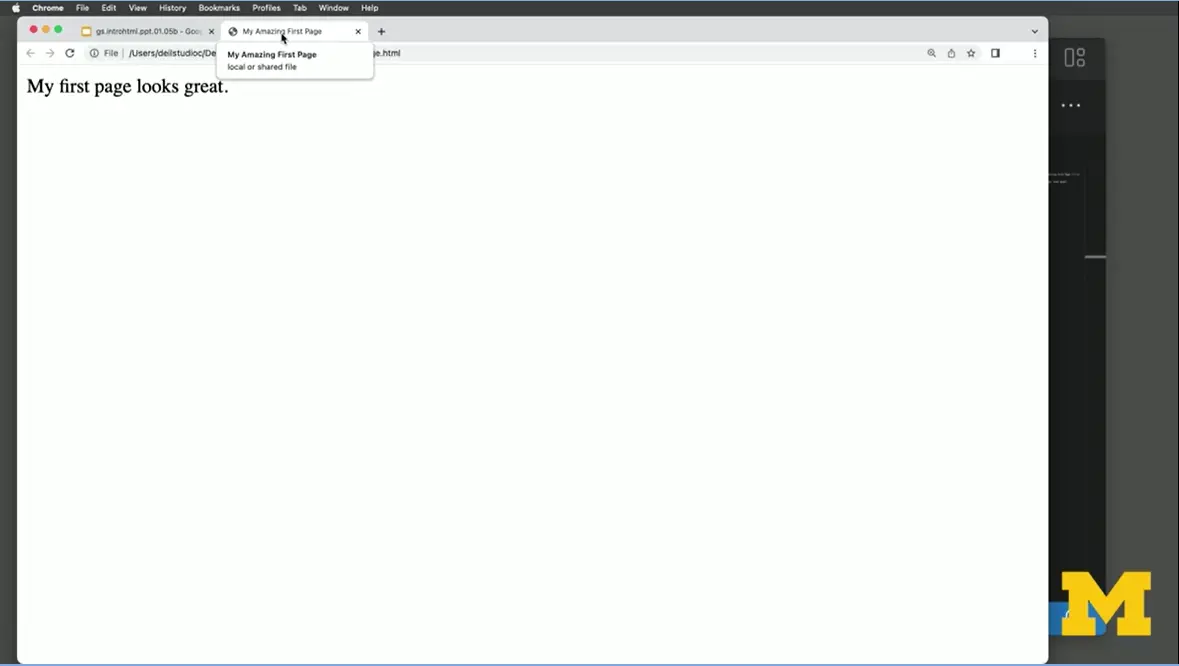

In an earlier lesson, I mentioned the importance of saving your work as you go along, which I'm going to do right now. Again, you can either use "File," "Save" or you can do the shortcut (ctrl-S). But once you look at your code, it's really important to make sure that you're always taking a moment to see what it looks like as well. One option for doing that is to go to your folder, find your first page and when we click on it, it opens up in Google Chrome.

I'm going to zoom in so you can see it a little bit better. You can see I have a title up here of, "My Amazing First Page." Let's say I want to go back and say, maybe my first page looks maybe not great, it just looks okay.

Because we're new, we have ways to improve. I'm going to save it. But when I go back over here, it still looks the same as it did last time. If you remember, changing something in the editor doesn't automatically tell your browser to reload it. I'm going to click here on the "Reload," and it now it says, "My first page looks okay."

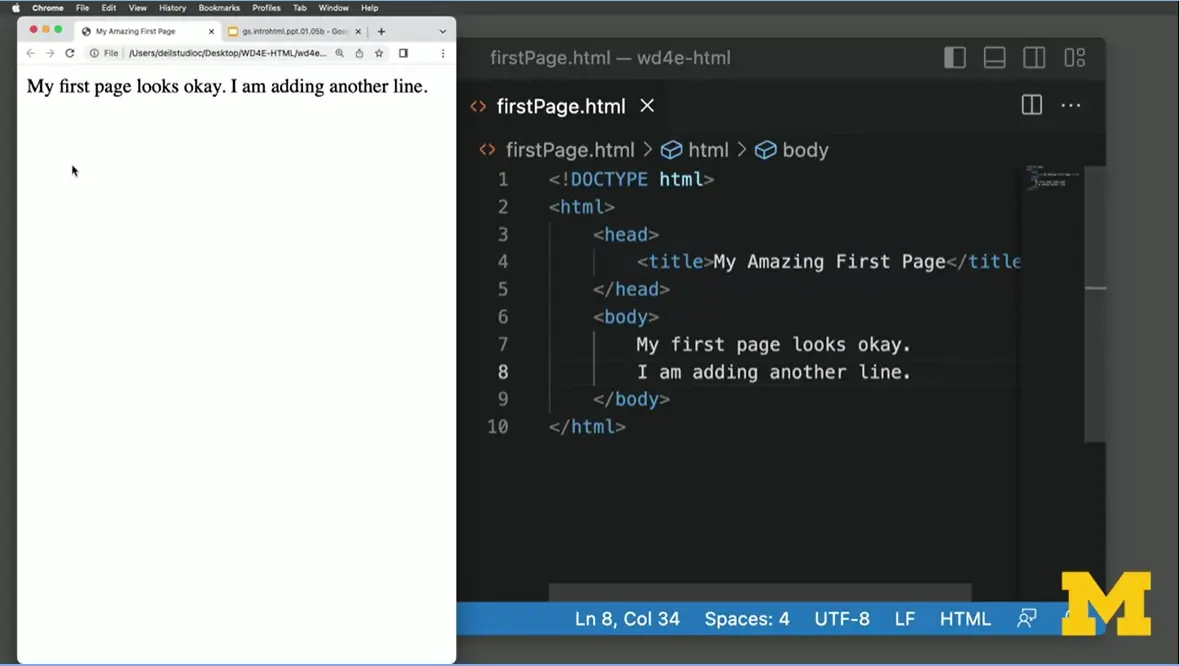

Personally, when I code, I like to have half my screen as the browser, and half my screen as text editor, so I can go back and forth and see both. I'm also going to go in here and add one more. "I am adding another line." I'm going to do "Save," and I'm going to do "Reload." One of the things you might notice is how things look in the editor is not always how it's going to look on the webpage, will learn how to fix that.

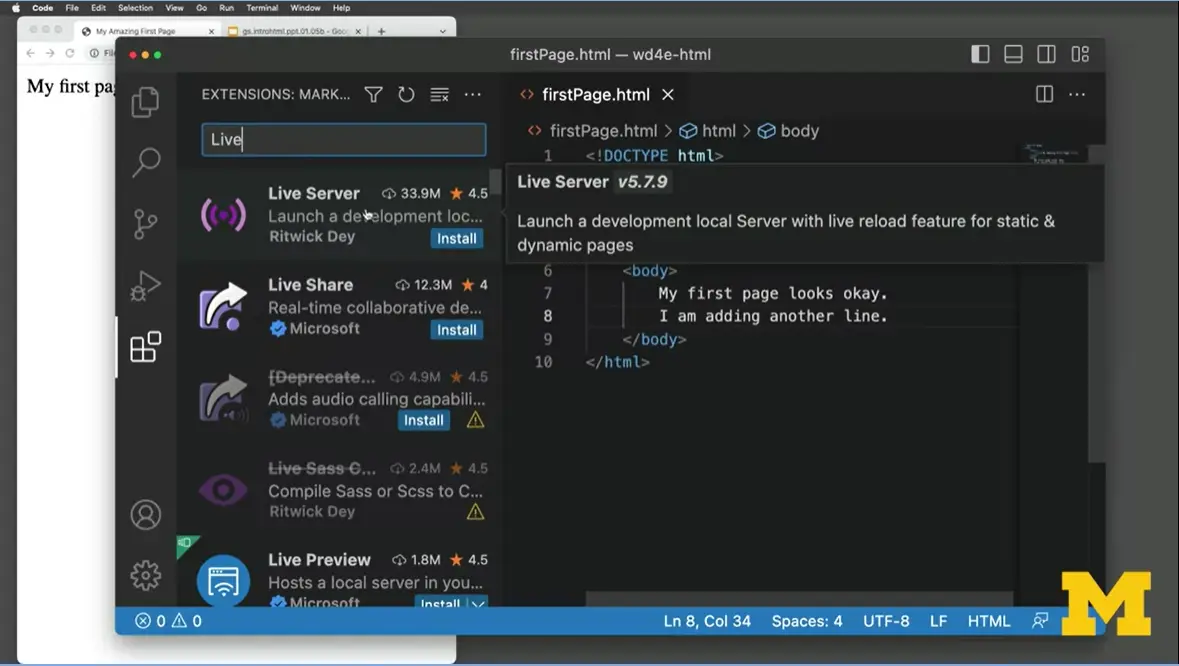

But I want to show you one more tip just in case you feel like Visual Studio Code is the editor you want to use. I'm going to click back on Visual Studio Code. I'm going to go the left-hand side, make a little bit smaller and go down to where I can find something called "Extensions." If you go to "Extensions," you will find something called "Live server." That right there, "Live server" by Ritwick Dey, install it. You can feel pretty good when you see something has 33.9 million downloads. I'm going to install it. I only have to do this once. That's it. I never have to do this again. As it installs, let me explain what Live Server does. Live server will let you see the changes you make as you type. I'm going to close this up here. I'm going to make sure that I can see both things on the same page.

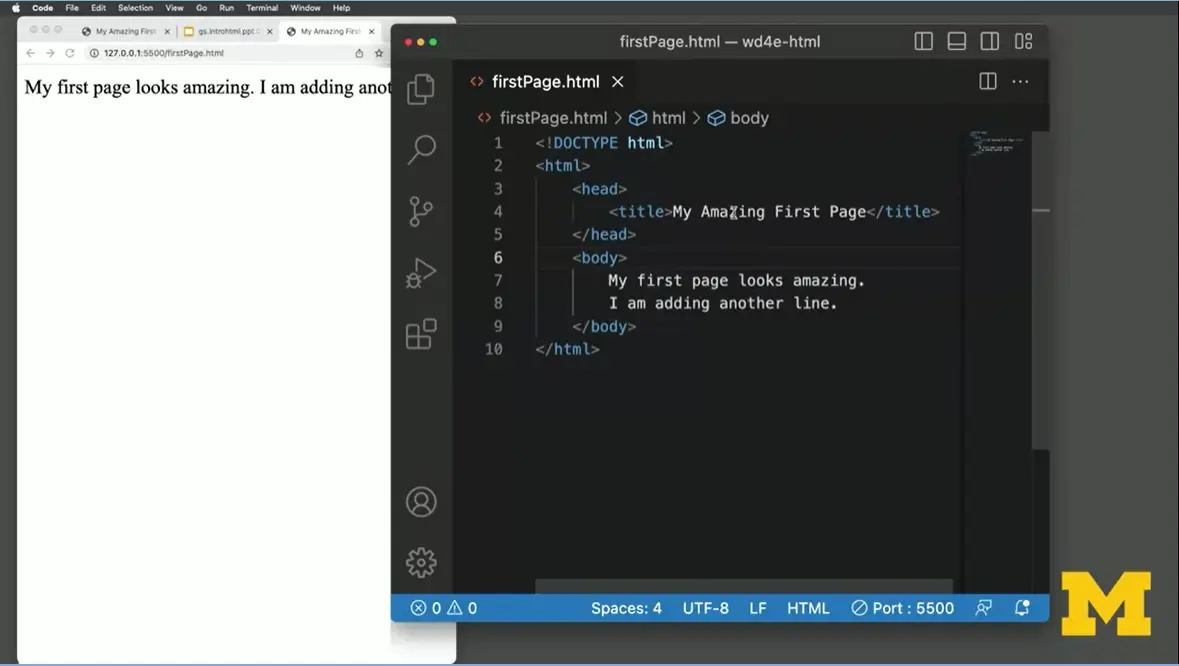

Now that I have Live server, I'm going to go down here to the bottom of the screen where it says "go live" at the very bottom. Now, every time I make a change, let's go back and say, "My page looks," we'll go back to, "amazing." Watch carefully, I'm about to hit Save. As I hit Save, it automatically showed on the other page. I could change my, um, I'm going to just to give you a sense, because Visual Studio Code is pretty cool. I'm going to type in just a little bit of Latin and when I do, it fills it all in for me.

So, when you use Visual Studio Code, the most important thing is to open it up and use proper naming conventions. If you would like, you can install "Live Server" and then from there we will go and learn how to add multiple files, multiple images, and lots of things that is going to make your webpage look amazing.

We highly recommend using Replit but Visual Studio Code (VSCode) is a popular editor that you may want to use as well – especially if you need to code without access to the Internet.

Some of the reasons people use VSCode are:

It’s free

It works on all of the major operations systems (Linux, Mac, and Windows)

It color-codes your file for easier debugging

It provides hover-over definitions, tips, and suggestions for any language.

It provides numerous tools such as auto-complete and the ability to view changes to your HTML page in real time.

For advanced users you can link it to your Github site for sharing with others.

If you want to use VSCode you will probably need to download it to your computer. Here is a trusted link: Download Visual Studio Code - Mac, Linux, Windows

Once you have the software installed you can watch the Getting started with Visual Studio Code. Don’t worry that they start with Python and JavaScript, they get to an HTML example about 5 minutes into the video! Make sure to focus on the parts of the video where you can open files, and the portion where they show you how to use Live Preview.

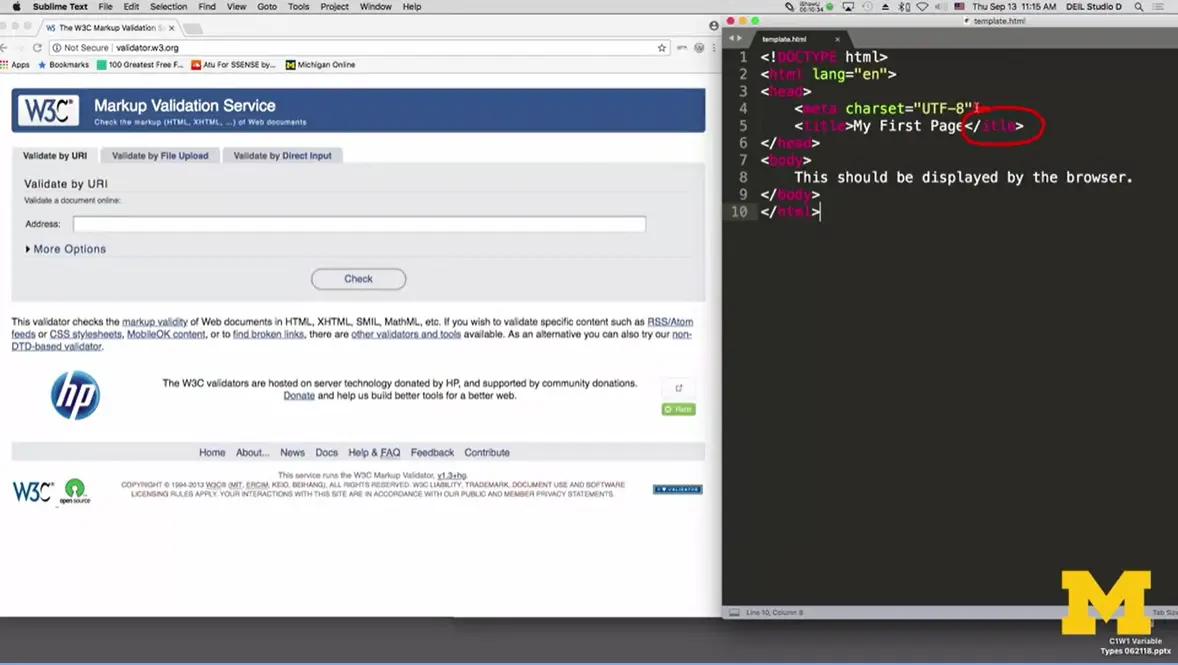

One of the most powerful tools in VSCode is IntelliSense – a feature that fills in code for you. For introductory students it can get confusing if VSCode fills in the code that you were expecting. So I encourage you to validate all of your code with the The W3C Markup Validation Service to ensure that you are writing syntactically correct code.

Earlier I mentioned that one of the editors I would highly recommend you use in this course is called "Replit," because I want to show you that writing code is great. Writing code that you can share online to show others your progress is also really exciting.

You've probably used online editors before. Google Docs and Microsoft 365 are common ways to share your documents. You can type something in, you can share it with your friends or your colleagues, and you can all make updates.

Sharing code is a little bit different, especially when you want to share your web page with someone. Do you want to share the code or do you want to share more with them that visual thing that you created? Today, we are going to use something called "Replit."

Replit is what we call an IDE, which is a fancy term called Integrated Development Environment. It lets you write your code, run your code, test your code, and share your code with others. Replit is an IDE that was made for beginner programmers. It doesn't mean that the first time you see it, you're going to be able to use it immediately but it does mean that it is built for people like you and I who want to make simple web pages and learn as we go along.

In this class, I will switch between using Replit and Sublime and Visual Studio Code. However, when you submit your homework, I'm going to highly recommend you using Replit because as I mentioned, unlike Sublime and Visual Studio Code, there are built-in tools for you to share your web page.

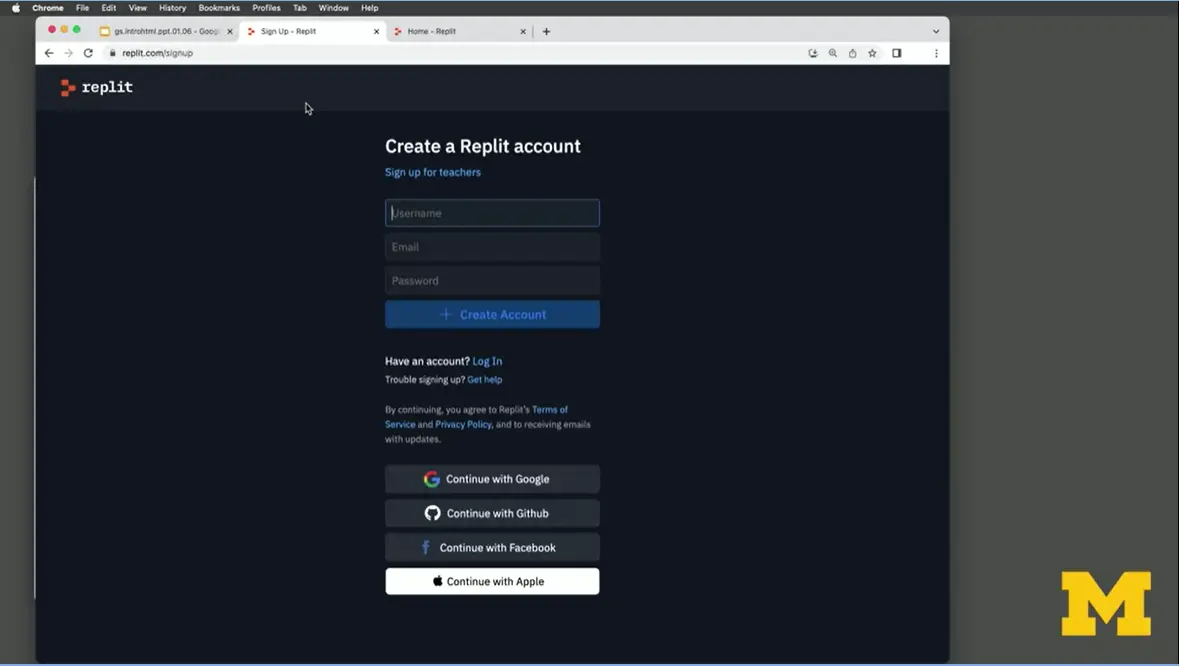

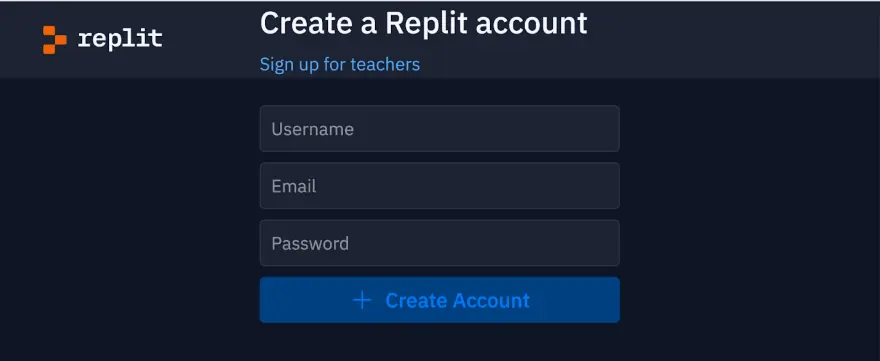

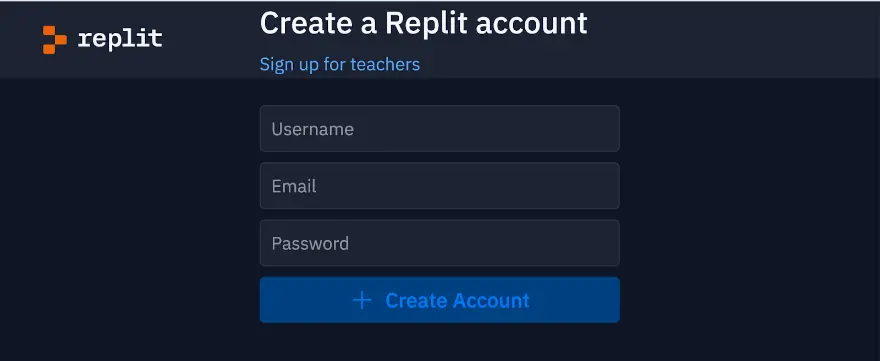

The first step to using Replit is to create a Replit account. You're going to want to create a username, provide your email and give them a password. But wait, wait wait wait, just one moment before you create that username, I want you to realize that the username you pick right now is going to be part of that URL for your web page. So pick something that's fun, representative view, or if you're hoping to make a site perhaps for family members, friends, a company, pick a name that you think that they would want to use as a front-facing part of their company or personality.

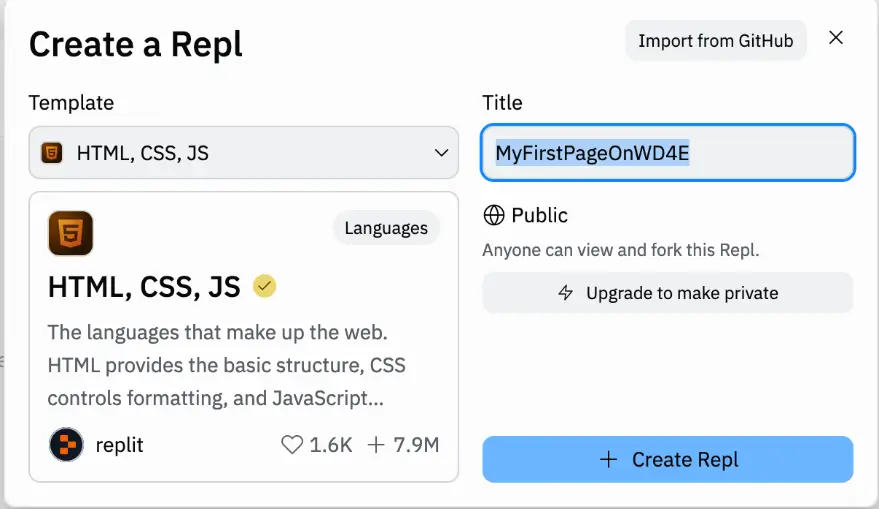

Once you're logged on, we're going to start off by creating a Repl. I'm going to click right down here on "Create Repl". It'll give you a number of different templates that you can use.

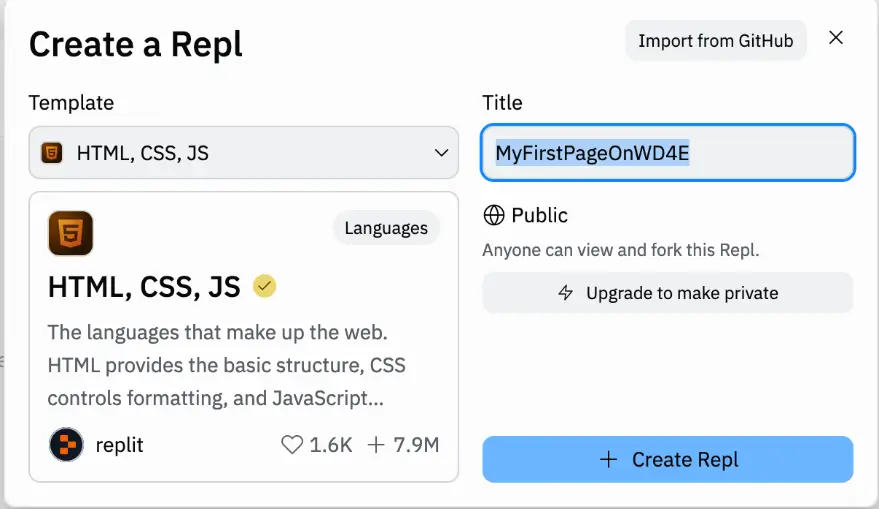

We will scroll down until we find HTML, CSS, and JS, which stands for JavaScript. Don't worry that we don't know any CSS or JS yet. We can go ahead and click on here.

The next step is to give our site a title. I'm probably not going to use AnguishedConcreteShockwave as they're recommending. Instead, I'm going to go ahead and use "MyFirstPage." As a reminder, I'm doing that "MyFirstPage," in fact, I'm going to do it the right way and make "my" lower case, the F capitalized, and the P capitalized. That's what we call camelCase. Anyone can see it, and I'm going to click on "Create Repl".

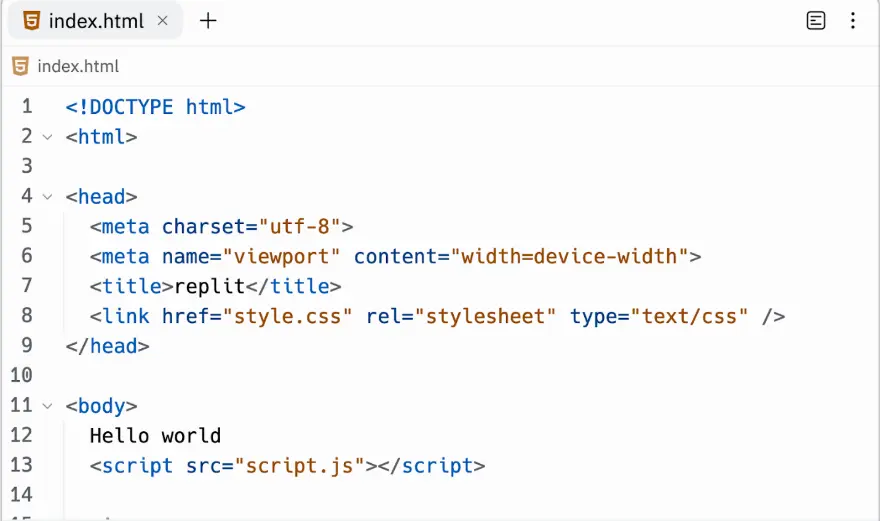

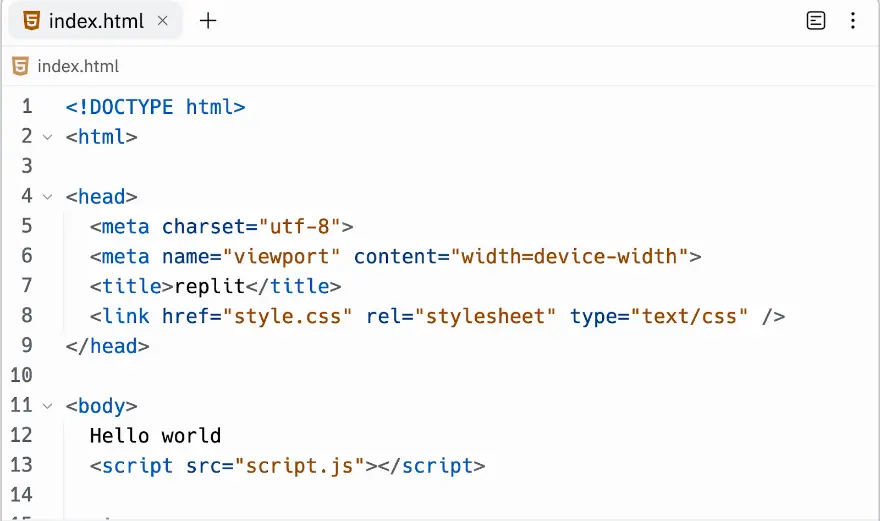

The first few times you log on, you're probably going to see a lot of helpful tips. I would recommend that you click through on all the next. However, for me, I've seen this before, so I don't really need to go through it. If you look, you will see that Repl has provided a lot of scaffolding for us, right?

It's gone in and it's given us a lot of code. It's provided that DOCTYPE HTML. It has a title for us, it's called "Replit" so I might change that to again, "My First Page" or something along that line. It's linked to something called a style sheet that we're not using yet so I'm going to delete that. Let's not get ahead of ourselves. It has "Hello world" and then it has a whole bunch of JavaScript. I'm just going to get rid of that too. There's no point overwhelming ourselves with code we don't need but I am going to say instead of "Hello world," I'm going to type in "Hello Colleen" and I'm going to do a command-S (ctrl-S) for save.

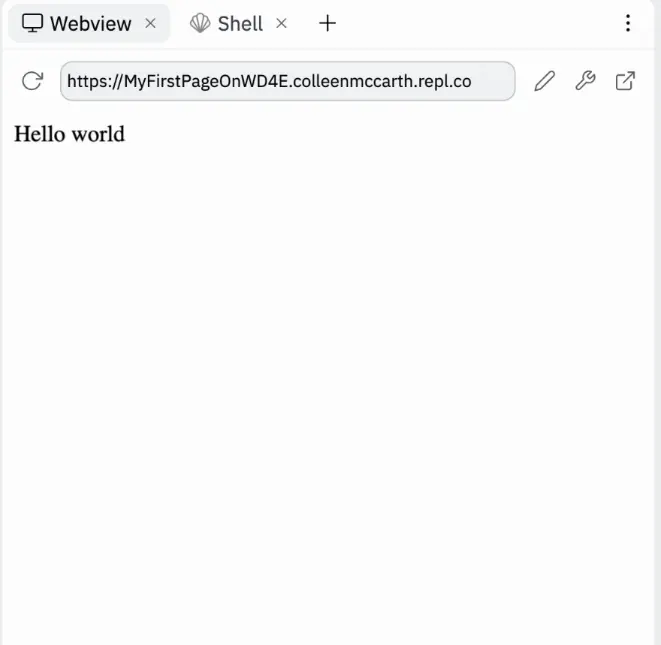

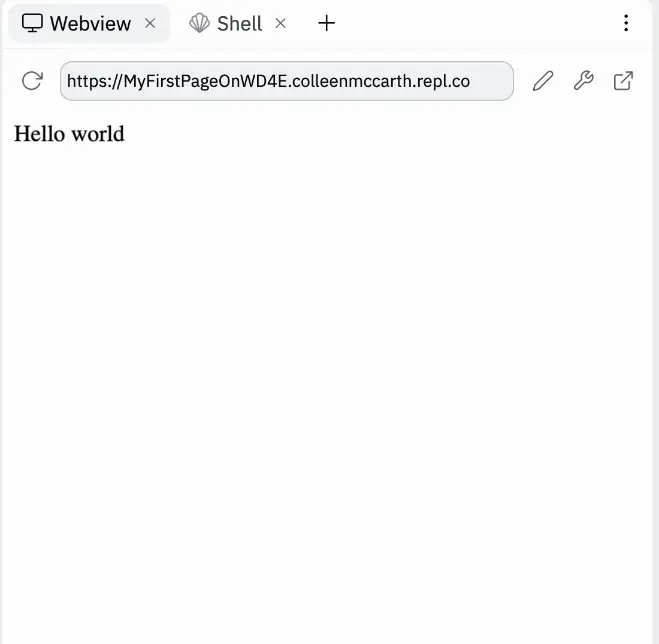

Did you notice something off here to the right? It will automatically show us what our page is going to look like as we type and save things. I could change this from "Hello Colleen" to "Hello Bacon" as you will all get to know, it's my very cute dog. "How are you today?" I'm going to hit "Save" again. Again for save, I'm going to do a command S. This is a really great part about being able to write my code, test my code, and see my code.

I want you to look and take the time to really check out Repl and see that you can see like, oh, I even have a real web page here. My web page is here. Notice that it deleted my CamelCase. It made it all lower case. The reason for that is because when you're typing in a URL, what's the chance that someone's actually going to remember to make some of them upper case and some of them lower case? You'll create files, you'll edit your files. While you edit them, you'll be able to see what they look like. This is why I'm recommending you use Replit.

Replit is what we call an Integrated Development Environment – this is a fancy term software that lets you do more than just edit your files. In this case Replit lets you create a page AND host it so that other people can see what you have created.

Replit is free, and the first step is to make an account.

Go to https://replit.com/

Select sign up

Create a username, provide an email, and create a password

At any time if you are asked to answer the optional questions (programming ability, light/dark mode, usage) you can skip them

Go to the email inbox you created your account with and verify your email

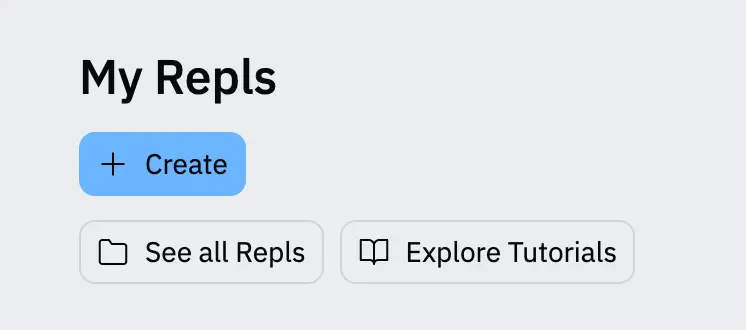

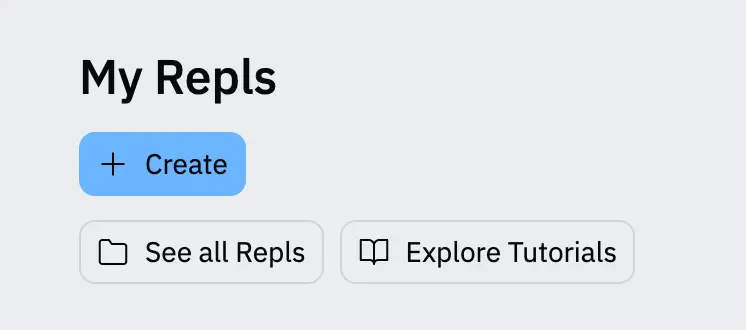

If you search the page you should find a heading titled: My Repls. Under that is a blue box with the words + Create. Select [+ Create]

A new screen will open and you will need to fill in some information:

Your template: set it template to [HTML, CSS, JS]

Add a title for your project

If you want to keep the project public: Yes

Click [+ Create Repl]

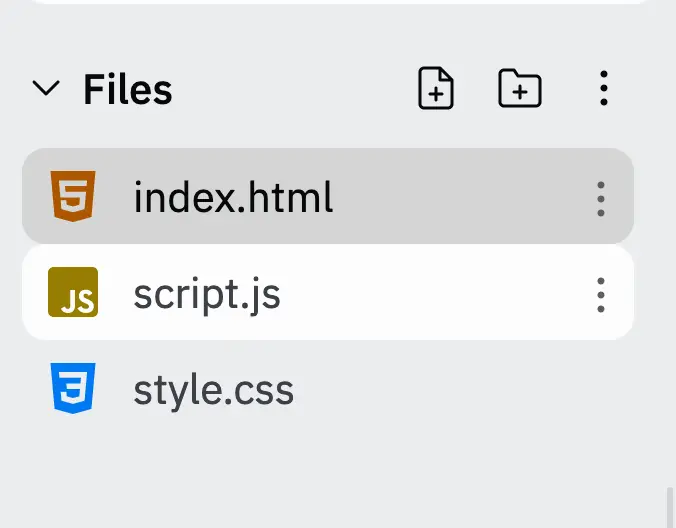

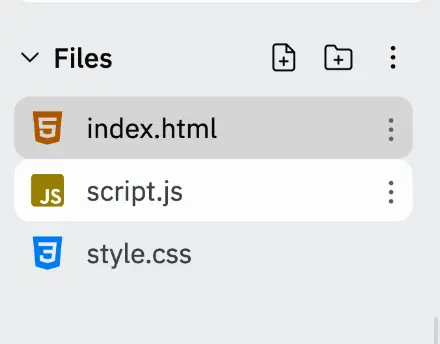

A tutorial will pop up and I encourage you to look through it to find out what the different parts of the IDE are. But for now the important thing is that you should be able to find three things: the Files section, the Coding Environment, and the View window.

The file section is located on the top left corner of the screen. This is where you can:

View all your files and file structure

Create new files by selecting the new file button in the upper right side of the file section. Name this new file and remember to use the correct file extension (.html, .css, .js) – Replit will create a template based on this extension.

Create new folders by selecting the new folder button and naming your new folder

The coding environment is located in the middle of the screen and is where you can edit your code.

As you make changes you can click the run button and Replit will display your index.html file in the Webview area on the right hand side of the screen. This is also where you can find the URL to share your site - it will be a combination of your username and the project name you chose when you created your repl.

This is also where you can find the URL to share your site - it will be a combination of your username and the project name you chose when you created your repl.

You can always go to the official Replit site for more detailed information on items such as:

Instructions on “how would you like to use Repel”

For education, for work, or for personal use

How can I save my file and add a new one?

Here are some optional resources for you to explore if you are interested in learning more about the topics from this week.

Interview with Joseph Hardin. If you are interested in learning more about the people who developed Mosaic, here is an interview with Joseph Hardin. The material in this video is just meant as a supplemental resource and is not required for the quizzes or any other evaluation.

The readings come from Learn to Code HTML & CSS: Develop & Style Websites and the W3Schools tutorials.

Some students prefer to do the readings before the lecture videos - they find it easier to listen when they recognize some of the words I am using. Some students prefer to do the readings after the lectures so that as they read they can connect it with what I said. Personally, I would suggest that you do the readings before AND after the lectures.

But no matter which method you chose, make sure you do the readings before the quiz. They go into more detail than my lectures and many of the quiz questions come directly from the readings. Also, make sure not to read the entire lessons for 8. They go into CSS which we are not covering in this course. (CSS is the next course in this series.)

To support learners, accessible lecture slides are provided as downloadable PDF files below, and individually within each lecture video. Please note, sometimes the slides will look slightly different from the videos since I like to update the slides when things change.

Week 2 Lecture Slides.pdf

Whenever possible, the code is linked through CodePen, Replit, and a downloadable zip file. You can choose the format that best suits your learning style.

You can find the code at HTML5 Course Code. It is organized by week, so you can check to see if any code is provided for this week's lessons.

Recognize the importance of accessibility and list steps to take when coding to enhance it.

Recognize and use common HTML5 tags.

Identify the parts of a syntactically correct HTML page.

Compose HTML5 code that can create images and links.

Identify the difference between syntax and semantics.

Let's talk about writing clean code. When I'm talking about clean code I'm talking about learning how to write code that's going to work on as many devices as possible.

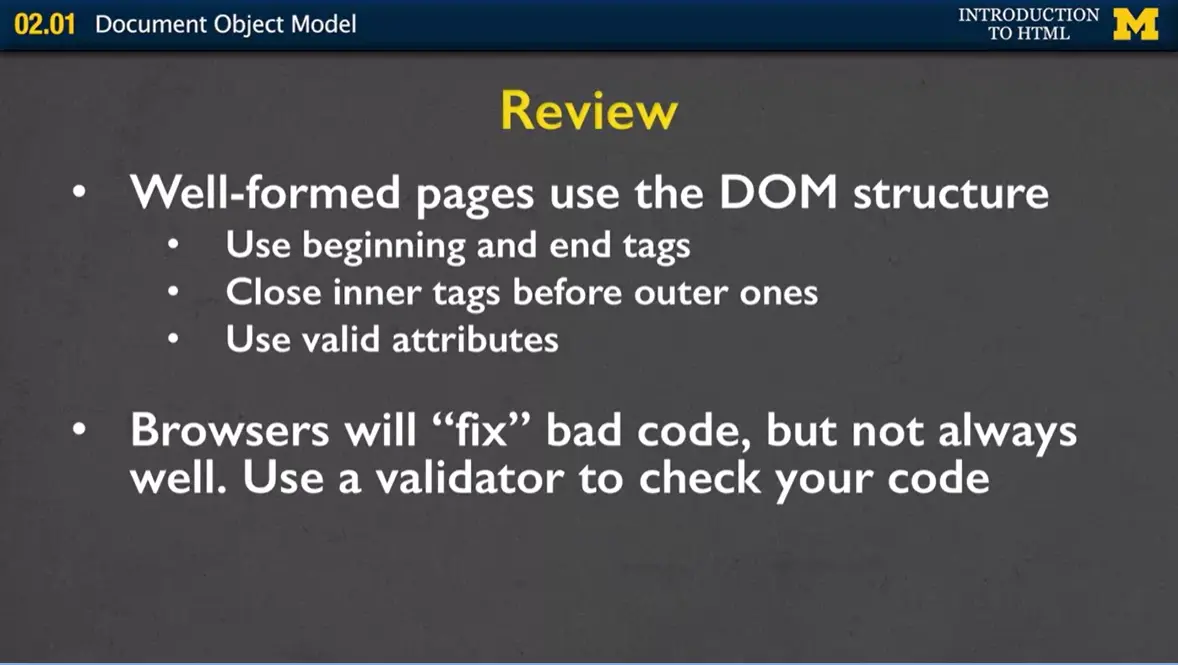

In order to do that, you need to know a little bit about the Document Object Model, also called the DOM. When HTML5 was developed the main kind of driving goal is that they want to stick by the standard. That any new features should be based on HTML, CSS, the DOM, and JavaScript, and you can have a chance to learn about each one of those. But I want to talk about the DOM for just a little bit because it's going to help you understand the HTML a little bit better.

One of the things about geeky computer scientists like myself is that we love trees. Not like trees out outside that are green and beautiful in the fall. We like mathematical trees. These tree-like structures that we can prove to be valid or invalid.

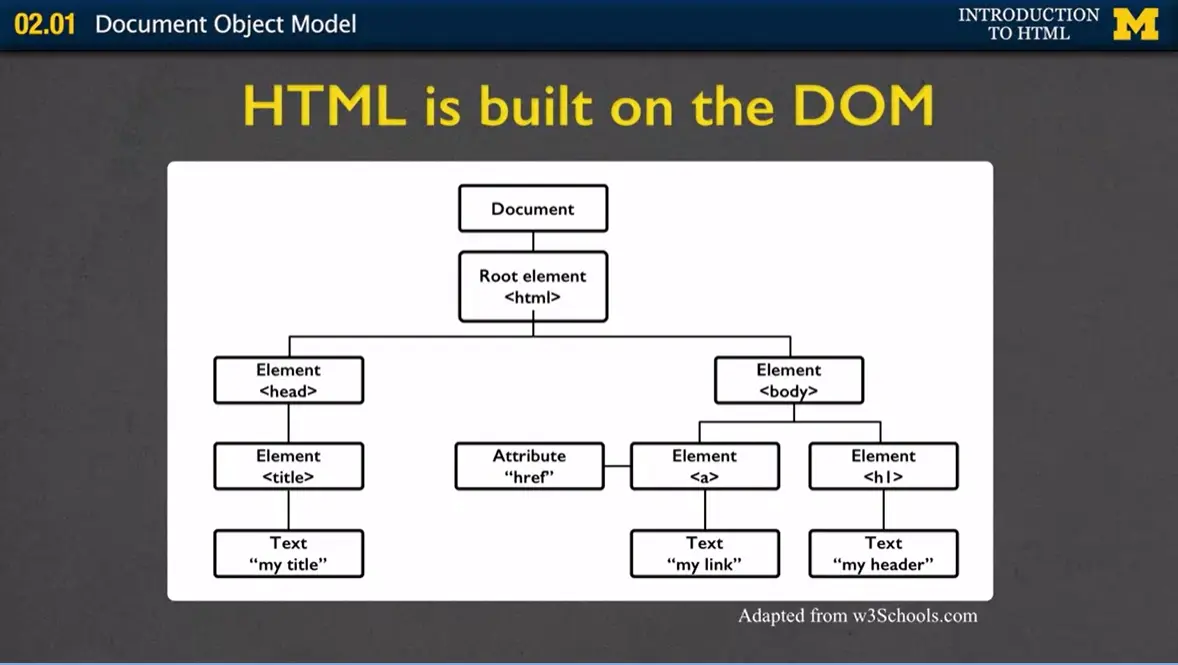

When we talk about HTML as a tree we're talking about this idea that at the very root of the tree we are going to be creating HTML. Then, from that tree when we say, "I'm going to make an HTML document." We want two parts. We want the head (on the left), and we want the body (the right of the root element).

In the head we're going to keep all that kind of information that the user isn't going to see for the most part. The one difference is we might talk about the title, but we're going to have all of that kind of hidden stuff nobody really cares about.

In the body is where we're going to learn to put all of our HTML5 tags. So let's talk about HTML as a tree. In this case I'm showing you this idea that at the root of every HTML page should be what's called the HTML tag. That kind of thing that says, lets the browser know, I'm going to be giving you certain types of tags and here's how I want them to work.

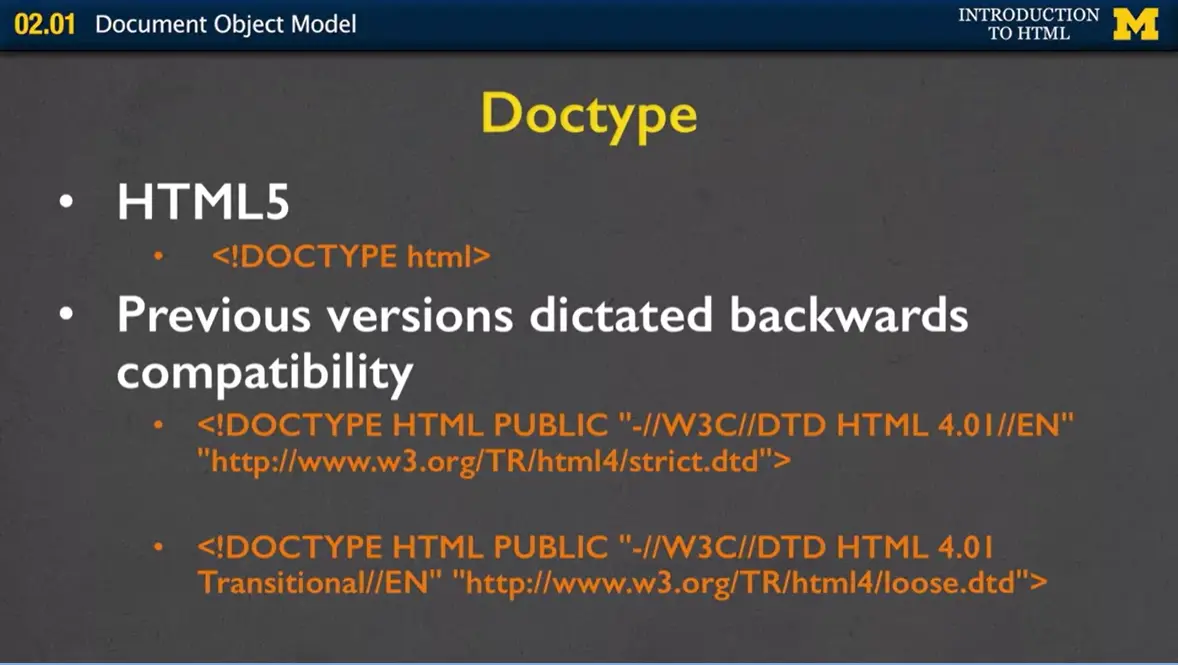

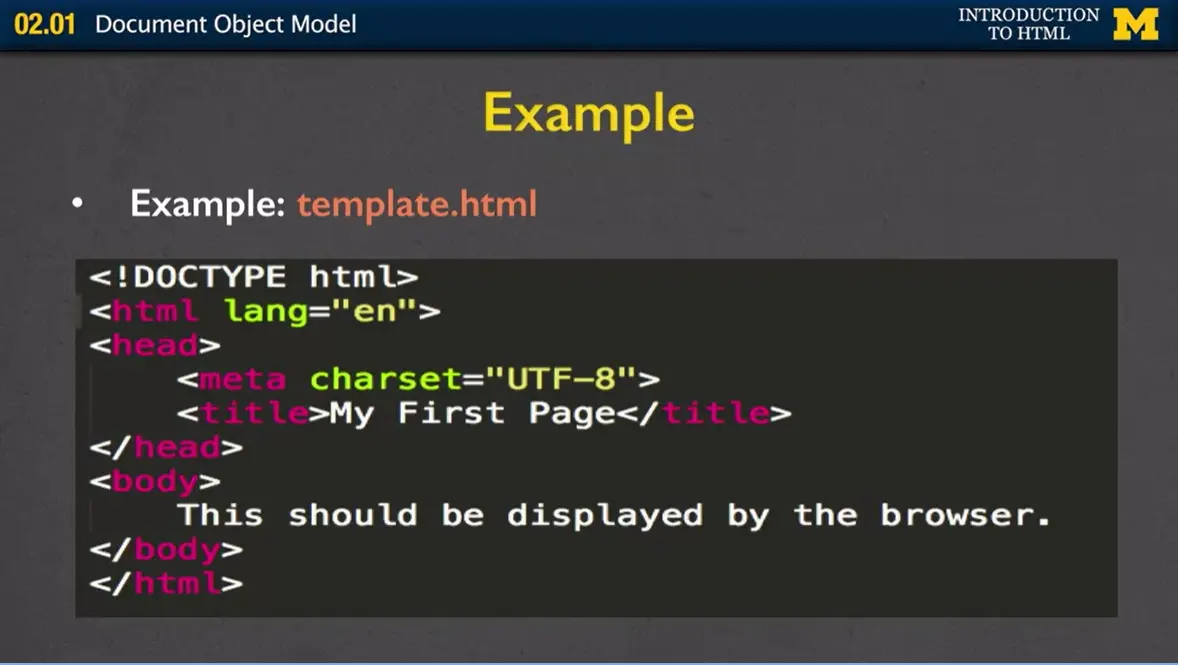

If we don't look at it as a picture, I can also kind of just tell you that every tree has three parts to a well-formed document. The Doctype, which is the version of HTML that you're going to be using. The head, which is all of the metadata or kind of extra information, and the body. The body is the displayable content. The thing that most people are going to get back when they do the request-response cycle.

So let's talk doctype. You are so lucky. When I was creating web pages at first and we were in HTML4, we had to come up with all these different ways to kind of explain whether our HTML4 was like very strict standards or whether it was transitional. In HTML5, it's very simple to say, "Nope, there's only one thing and it's called DOCTYPE HTML, and you're all set."

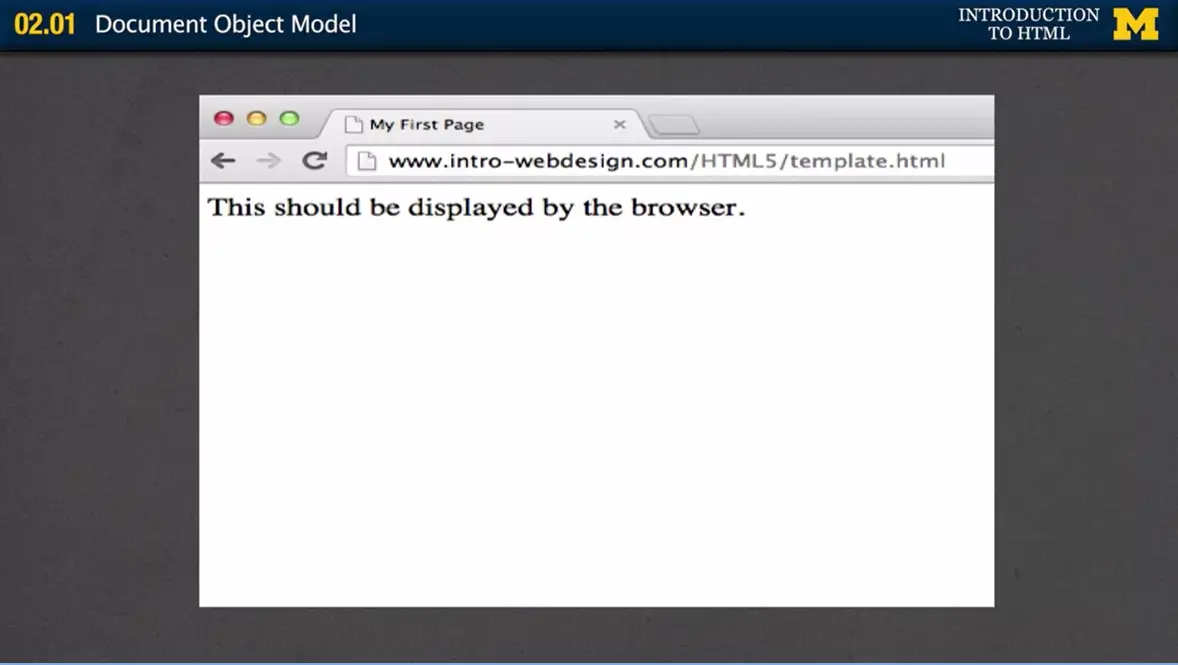

For the head which is inside the head tag, we're going to have all this additional information used by the browser. For instance, you might want to say what language you're creating your page in. You could also include, and you really want to include, what the title of your pages. When I am talking about the title I'm not talking about big kind of header that you see. I'm talking about the little tiny thing you see in the tab of your browser.

Later, you might want to add supporting files as well. You might want to have CSS files that will style your page, or JavaScript that can add on different interaction, or really any type of add-on that's going to change the way people view and interact with your site. Other than the title, the metadata is not displayed, people will not see it.

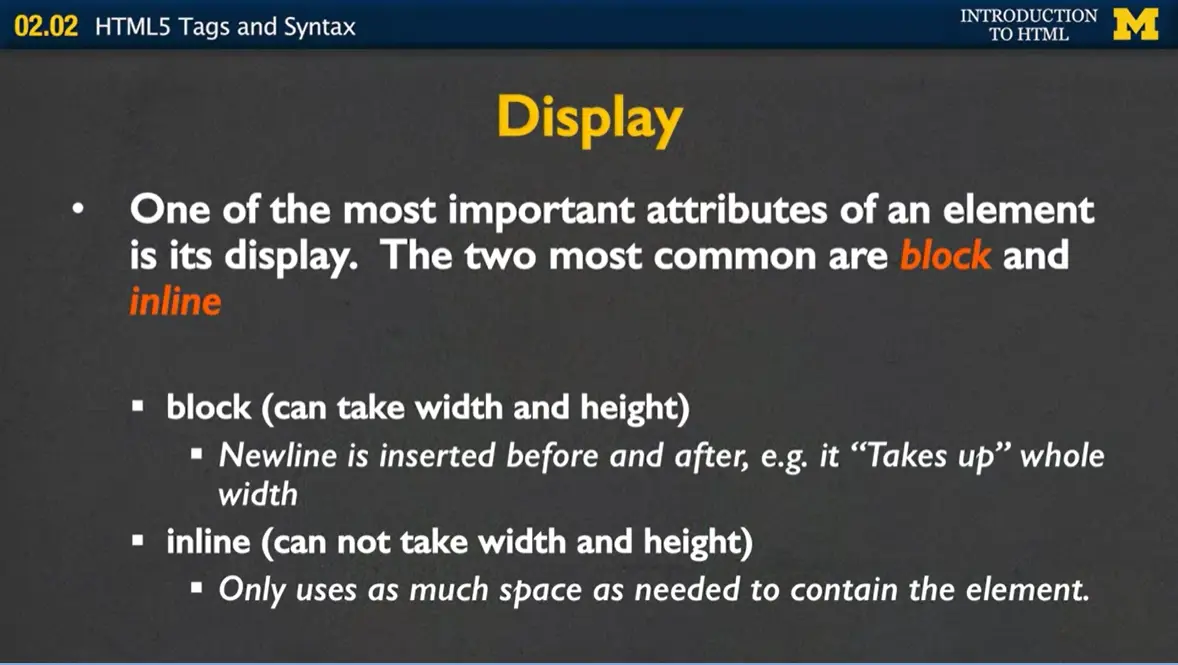

What people do see is the information that's in your body tag. That body tag is the bulk of your page. It's very important to write well formatted or tree-like code where you're making sure that every tag has an end. That you're not putting tags in weird orders. Most of the content in the body is displayed by the browser but every once in a while there's a little bit of metadata in there too. But we're not going to hit that in this class.